In the summer of 1952, the brutal murder of a woman in a Kensington hotel shocked Britain and sparked a media frenzy: no ordinary victim, Christine Granville was a Polish beauty queen turned British secret agent, the newspapers breathlessly revealed, a countess by birth whose remarkable bravery during the Second World War had saved countless lives. But the sensationalist cover stories couldn’t hope to capture the full tragic irony of Christine’s sordid, pointless death at the hands of a spurned lover. Over the course of her wartime career, a gift for repeatedly escaping the deadliest of situations—into which she walked with the eager nonchalance of a true adrenaline junkie—had conferred mythical status on the slender, dark-haired daredevil. Dying as a civilian in peacetime, with nothing and no one at stake, was an almost comically cruel twist of fate.

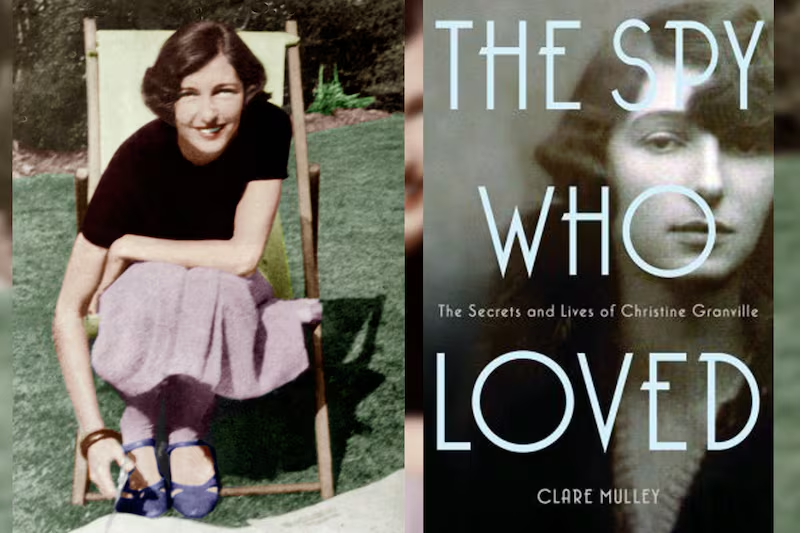

Not only did the hush-hush nature of Christine’s work mean that few specifics of her feats were known outside of espionage circles, but when she died, many of her friends conspired to draw a veil over the details of her life—in particular her spectacularly diverse romances, from which her intrepid exploits were often inextricable. The Panel to Protect the Memory of Christine Granville, for example, comprised five friends and former lovers who wanted to “defend her memory” and prevent her from becoming “a press sensation”; several biographies and articles were consequently quashed. While a few books about Christine have emerged in the intervening decades, only now, with the publication of Clare Mulley’s scrupulously researched and expertly rendered biography, do we have a multidimensional, uncensored, impartial portrait of the legendary spy—said to be Churchill’s favorite—whose 44-year existence was filled with more eye-popping adventures than we’d find plausible in any novel or movie.

Even Christine’s provenance is the stuff of fairy tales. Born in Warsaw in 1908 to a charismatic, dissolute aristocrat and a beautiful Jewish banking heiress, the baby christened Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek began life in a country that didn’t officially exist: Warsaw was then part of Russia and would remain so until Poland gained independence in 1918. Regardless, the Skarbeks considered themselves Polish nobility, and their daughter was raised in bucolic splendor on a country estate “so large, it contained three villages.” True, some tensions hovered regarding her mother’s Jewishness—Count Jerzy Skarbek had married Stefania Goldfeder for her money, she in turn sought his social position, and her conversion to Catholicism offered little immunity from anti-Semitic gossip and snobbery—but Christine adored both her parents and thrived in her privileged surroundings, climbing trees, riding ponies, even learning how to use a knife and hold a gun. By adolescence she had acquired the remarkable self-assuredness, and personal magnetism, that would define her destiny.

Those qualities were needed sooner than she might have expected: thanks to the post–World War I depression, the Goldfeder bank collapsed and with it the Skarbek family’s grand lifestyle. At age 21, Christine was living with her mother and brother in a modest Warsaw apartment, her father having abandoned his marriage. Soon a habitué of the city’s bars and nightclubs—flouting, all too characteristically, the social prohibition against unchaperoned gallivanting for well-to-do young ladies—Christine also got herself a job at a Fiat car dealership. One customer, a successful businessman named Gustav, would become her first husband: a few years older than her and a good few inches shorter, he was nevertheless wealthy, which meant she could offer her mother some much-needed security. He, meanwhile, was delighted to marry a national “star of beauty”—Christine’s newly minted beauty contest title. But not surprisingly, given her voracious appetite for freedom and Gustav’s hankering for bourgeois domesticity, the marriage lasted barely two years. Gustav would later describe his ex-wife, quite accurately, as “dotty, romantic, and forever craving change.”

Christine’s second husband, named Jerzy like her father, was a better match. A sometime diplomat and former cowboy and gold prospector, like her he combined gutsiness with a total disregard for convention. Still, when the couple was traveling in South Africa and heard the news that Germany had invaded Poland, Christine harbored not the tiniest qualm about leaving Jerzy in a rush to defend her beloved homeland. Presenting herself to British Intelligence in London—“a flaming Polish patriot ... expert skier and great adventuress,” according to their records—Christine volunteered to ski into Nazi-occupied Poland armed with British propaganda. Her fervent aim, writes Mulley, was “to bolster the Polish spirit of resistance at a time when many Poles believed they had been abandoned to their fate.”

That mission, carried out with a Polish Olympic skier turned mountain courier, set the tone for Christine’s career in its sheer wildness. Heading out from Czechoslovakia during the coldest winter in living memory, with snow four meters deep, the pair traversed the 2,000-meter-high Tatra Mountains, seeing two dead bodies on their way and later hearing that, on the night they reached the border, more than 30 people had died in the mountains trying to escape Poland. Then, once on a Warsaw-bound train, Christine’s nerve did not desert her: realizing that armed guards were doing spot checks of passengers’ possessions, she directed the beam of her preternaturally bewitching allure onto a uniformed Gestapo officer. Would he mind, she wondered, carrying the package of black-market tea that she was bringing her mother? He happily obliged, and so her sheaf of illicit documents—which, if discovered, would have led to merciless interrogation followed by the firing squad—reached their destination.

Such boldfaced aplomb would be deployed time and time again in dealing with the Nazis. When working for SOE (Special Operations Executive, the secret wartime sabotage unit) in the Alps, where she trekked between the French and Italian sides and transmitted vital information about enemy activity, Christine was stopped by the German frontier patrol. In her hand she held a silk map of the region, given to agents to avoid the giveaway rustle of paper in pockets. With no hope of concealing it, she casually shook the fabric out and used it to replace the headscarf she was wearing, greeting the soldiers in French as if she were simply a local on an errand. Another time she and Andrzej Kowerski, her on-off lover and frequent partner in crime, were arrested and interrogated by Gestapo officers in Budapest. Christine had been suffering from flu, so she exaggerated her hacking cough and bit her tongue so hard that she appeared to be bringing up blood. Presumed to be infected with tuberculosis—potentially fatal and frighteningly infectious—she and Kowerski were released.

Christine’s most jaw-dropping act of heroism would occur in August 1944: with a bounty on her head and her face having graced “Wanted Dead or Alive” posters, she strolled into a Gestapo-controlled French prison and, posing as another woman entirely, secured an interview with a corruptible gendarme. Every iota of her charm and resourcefulness coming into play, Christine successfully arranged to break out three colleagues—including her lover du jour, the 29-year-old Belgian-British agent Francis Cammaerts—who were about to be executed. “Good reading,” an SOE officer wrote on the cover note of Cammaerts’ subsequent report, “I am going to make sure that I keep on Christine’s side in future.” “So am I,” another scribbled in reply. “She frightens me to death.”

Disgracefully, despite Christine’s well-documented valor, after the war her former employers more or less abandoned her. Without a job, the British government dragging its feet over whether she was even entitled to citizenship, and her motherland under the thumb of Stalin, the heroine, lauded by a diplomat friend as “ready to risk her life at any moment for what she believed in,” was eventually reduced to working as a waitress in London, then as a cruise-ship stewardess. It was on one of these voyages where she met Dennis Muldowney, a steward from Wigan who became dangerously obsessed following what was, for Christine, merely another casual fling. Previously her disinclination to settle down in an exclusive relationship had fit perfectly with her roaming, tumultuous spy’s existence, and her lovers, typically men as cosmopolitan as she, had tended to grasp the futility of trying to tie her down. But for Dennis—insecure and inadequate, damaged from an abusive childhood—to be rejected by the most glamorous and sophisticated woman ever to enter his humdrum life was enough to drive him insane. After hiding in wait at the Shelbourne Hotel, he stabbed Christine straight through the heart. “To kill is the final possession,” were his last words before he was hanged.

In a poignant postscript to Christine’s story, in 1971 the Shelbourne Hotel came under new management, who cleared out the storerooms. With Christine’s untouched possessions—her trunk, her SOE wireless, and commando knife—was an oil painting of her by society artist Aniela Pawlikowska. It was to have been a gift for Kowerski, Christine’s longtime lover, fellow war hero, and closest friend, whose marriage proposal she had finally accepted. The portrait, in which she’s wearing pearls and her Skarbek signet ring, today hangs in the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London—a modest afterlife now endowed with its true majesty by Clare Mulley’s outstanding book.