There is a persistent and erroneous belief that the Eskimos have 50 (or 70, or 300) words for snow. Foibles like this betray insecurities about our native tongue, and we tend to find a word more interesting if it comes from a foreign land, as anyone who has been introduced to schadenfreude knows. There is a frisson that comes from hearing the previously unknown meaning of an alien word—it carries with it a whiff of the exotic. A small lexical unit can transport you to a distant clime and leave you feeling dissatisfied with the insipidity of your native speech. “Why,” you might wonder to yourself, “must my own words be so lacking in inspiration? Why must I speak the speech of Podunk?”

Americans, rejoice—you can now be swept away to the foreign land of your own language

Termatusses. Tady-wampus. Spizzerinctum and ujinctum.

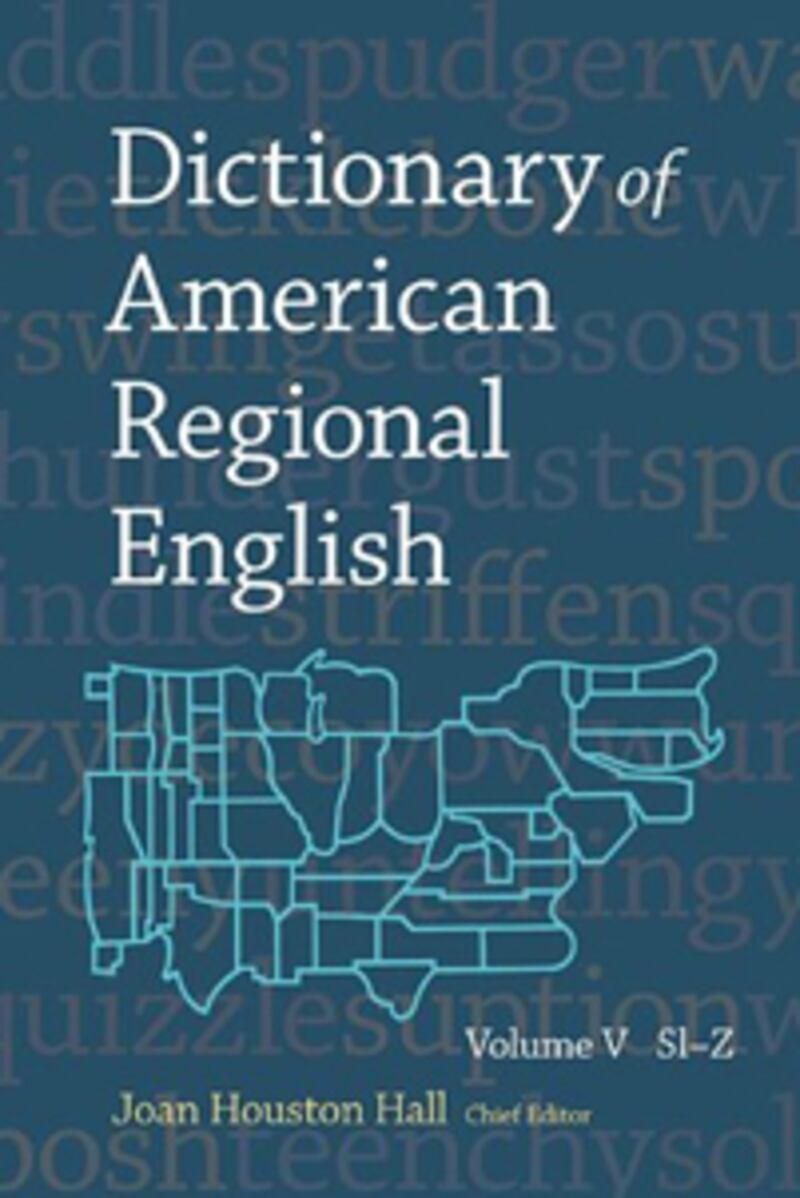

The words are not cribbed from some long-forgotten and unpublished Lewis Carroll poem; they are all part of our native language, and refer respectively to a tomato, an imaginary creature, ambition, and Hell. You would be hard-pressed to find them in most dictionaries, but this does not mean that they do not exist. And now these oddly-shaped critters may be found collected and defined in the fifth volume of one of the 20th century’s great lexicographic projects.

This month marks the publication of the final volume of the Dictionary of American Regional English, a weighty 1,000-plus-page work with the singularly descriptive title of “Sl–Z.” DARE has been a work in progress for over half a century: its fieldworkers have been collecting words and pronunciations from Americans in more than 1,000 communities since 1965. These nomadic lexicographers traveled in vans that they called “word wagons,” interviewing speakers in all 50 states in search of examples that were regional or archaic enough to not be included in the dictionary.

The results are stunning. The variety and inventiveness of English is arranged on the pages not as dry text but as a living tapestry of language. The entries cover the geographic range from words and expressions used only in Hawaii (tutu—a grandparent) to those used only by the Gullah communities of South Carolina and Georgia (truth-mouth—one who speaks only the truth), and every state in-between. Fieldworkers were instructed to collect language from speakers of all ages, and the result is that they captured both the incipient usage of the young as well as words of the elderly that are disappearing (or have already disappeared) from our lexicon.

The inclusion of phrases in addition to single words provides an opportunity to revel in the whimsical twists of our tongue. Americans turn their phrases toward the poetic (walk uphill—to be pregnant), the mocking (whistle-britches—corduroy pants), and the visceral (vomit up one’s toenails—self-explanatory).

Consider some of the best entries:

1. soft-shell Baptist: “Such are the soft-shell Baptists, so called on account of their less stern manners and less rigid principles, which allow them to be indulgent to certain worldly usages, and to educate their ministers carefully for the pulpit.”

2. solemncholy: Very solemn or melancholy.

3. sollybuster: An unusual or extraordinary thing, especially of a large size.

4. sputterbudget: A finicky, fussy, or fretful person.

5. strut fart: One who struts around, highly conscious of his own importance.

6. suffancified: Satisfied. Used as a humorously exaggerated formula of politeness when refusing food.

7. unfinancial: 1. Of a member of an organization, esp. a fraternal order: in arrears on dues, not paid up. 2. Insolvent, out of money.

8. waistline party: A party in which the price of admission is based on the size of one’s waistline.

9. white man’s fire: A campfire that is larger than necessary.

10. wunnerfitz: A nosy person.

One could paraphrase George Barnard Shaw’s quip that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language” and apply it to the 50 states instead. We’ve got words from Yiddish, Swahili, French, Italian, and dozens of other languages. Some words exist only in Wisconsin. Some are used in every state except for one or two. We’ve got such a variation that it’s hard to believe we can understand each other at all.

This is a dictionary that was crowdsourced before crowdsourcing was a common online behavior. The entries are provided by people who use them. They are then sorted, defined, and given additional citations by a team of trained lexicographers, who provide citations illustrating how these words are used, extracted from sources as diverse as factory workers in Maine and William Faulkner.

It is hard to resist comparing this to the online Urban Dictionary. DARE is, in a sense, what Urban Dictionary could be, if you forbid bored and semiliterate teenagers from including words and definitions of their own invention.

As is the case with any dictionary worth its salt, reaching the letter Z represents an opportunity for DARE to begin work anew. The mutability of language is itself immutable, and English never stops growing and changing. There are currently plans to make the entire dictionary accessible and searchable online by 2013, and more lexical data is always being collected. As some of the denizens of its pages might say, it’s a whoopensocker of a book, and you’d have to be meaner than turkey-turd beer not to appreciate it.