In the 1985 blockbuster Back to the Future, California teen Marty McFly journeyed back in time to save his present. The film’s universal themes are known around the world, and Chinese leader Xi Jinping appears to have internalized them as he approaches the most fraught moment of his political career. What Xi lacks in a time-traveling DeLorean, however, he more than makes up for with the theory of “continuous revolution,” as first championed by Mao Zedong.

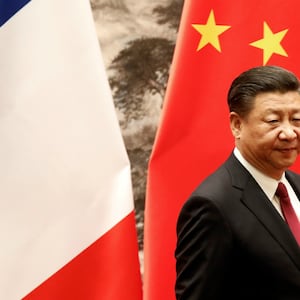

Xi’s re-election campaign, which could see him anointed leader for life, unofficially began more than two years ago when he eliminated term-limits from China’s constitution. But it was not until this July’s Chinese Communist Party centennial celebration, and a fiery speech mere steps from Mao’s tomb in Tiananmen Square, that Xi truly kicked his campaign into high gear.

China watchers have long mused about the many similarities between Mao and Xi. Both came of age during a time of great socio-economic upheaval, and both led China through periods of intense international pressure. The difference, though, between Mao’s past and Xi’s present is that China itself has changed. The country and its people are more connected to the outside world than at any point in Mao’s era, and the party itself is more accountable to Chinese public opinion. Which raises the question: If the geopolitical game has changed, does Mao’s playbook still apply?

Mao’s revolutionary zeal and deep affinity for asymmetric warfare were borne out of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. Front and center in China’s victory was Mao’s concept of a “united front,” which entailed unifying all of Chinese society, nationalists and communists alike, to defeat the country’s then-main adversary, Japan. After consolidating power and expelling the nationalists, Mao recycled the term “united front” throughout his reign, first when partnering with the Soviet Union against imperialist forces and later against the Soviet Union itself after the 1960 Sino-Soviet split. Central to Mao’s foreign policy, beyond his role as China’s sole decision-maker, was his strong emphasis on security and sovereignty, as well as his attempted elevation of China’s international prestige.

But like any good revolutionary seeking job security, Mao realized early in his tenure that the key to sustaining his political longevity was not simply eliminating rivals. Rather, it was about mobilizing the masses, namely through the adoption of a revolutionary foreign policy centered around crisis creation. In casting the People’s Republic of China’s birth as the first step in a long revolutionary march—one linked to an ill-defined destination —Mao successfully managed to enhance his own authority and legitimacy.

Fast-forward to the last two months in China, which were marked by a policy blitzkrieg geared toward deepening the party’s ideological dominion over the country. In a series of crackdowns aimed at reining in private business and redirecting entrepreneurial energies in service of the party’s priorities, Xi, tapping into memories of Mao’s cultural revolution, reminded Chinese entrepreneurs that they are dispensable tools of the party.

In a move reminiscent of the 1960s and early 1970s, China’s education curricula will now be centered around permeating party ideology deeper into the minds of the masses. This time, it will be Xi Thought reinforced in children’s textbooks and blasted from loudspeakers in the countryside. Not even video games are safe, with the government now restricting daily play to one hour. The net effect of these moves is that entrepreneurs will be more willing to comply with the party’s demands and intellectuals more inclined to stay silent.

Xi has announced these and other policies under the banner of his latest rallying slogan, “common prosperity,” which aims to improve standards of living and to address the widening rich-poor gap, both of which threaten Xi and the party’s long-term legitimacy. Even less clear is how these draconian, Maoist measures fit into Xi’s even grander ambition of bringing about China’s “great rejuvenation,” a term which Xi and his acolytes have never defined. But as Mao also dreamt, it ensures that China’s revolution can continue indefinitely, and all in the name of Xi’s political survival.

Which explains the events leading up to President Biden’s most recent phone call with Xi, one ripped directly from Mao’s script. The White House sought to frame the call as an opportunity to conduct a “broad, strategic discussion” following months of unproductive, lower-level engagements. Of course, the inability of lower-level Chinese and American officials to make any meaningful headway was largely by Xi’s design, one that places him, not his lieutenants, at the center of China’s relationship with its external rival, the United States.

The call also occurred only days after the end of the annual conclave of party heavyweights in Beidaihe, one geared toward discussing policy and high-level appointments. This year, however, there are reports that Xi may have not even bothered to attend, a sign that he has so thoroughly consolidated power that he makes personnel and policy decisions on his own without any input from party bigwigs. Somewhere, Mao must be smiling.

Xi’s emphasis on leader-to-leader exchanges is thus a personification of his Maoist tendencies, and one certain to persist until his re-election in 2022. What’s more, Xi appears unlikely to outsource control over any major bilateral decisions that could impact, positively or negatively, his own political standing. This includes meaningful progress on climate change negotiations, which Xi has smartly dangled before a White House eager to deliver on its domestic priorities. Whereas China’s historic pragmatism and reliance on exports may have previously constrained Xi’s revisionist behavior, he—like Mao—increasingly sees China’s fate as less dependent on outside influence. It is a political calculus that sits at the center of China’s 14th Five Year Plan, one focused on building up China’s domestic economy.

Like Mao’s consolidation of power, in the coming year Xi will also further intertwine foreign and domestic crises, even at the risk of potentially serious flair ups with Washington over Taiwan. The first true test will come this month, when the U.S is expected to allow the Taiwanese government to change the name of its representative office in Washington to include the word “Taiwan.” Just how Xi intends to navigate a wholesale restructuring of China’s economy and increasing tensions over Taiwan remains unclear — even to him, it seems.

What is clear, however, is that to get wherever they are going, which presumably does not include a war, Xi and President Biden are going to need to build some personal in-roads. It is a challenge made all the more difficult for Biden given Xi’s refusal to travel outside of China for more than 600 days and counting. For now, the best Washington can do it buckle up, and hope that Xi’s sequel is a whole lot better than Mao’s original.