There’s a moment in the fifth episode of FX on Hulu’s new graphic novel adaptation Y: The Last Man that quietly and quickly remarks on the limits and accomplishments of the screen remix. A global event has exterminated every mammal with a Y chromosome, ripping through the giant halls and dark corridors of the White House, where two women—one recognized as the new President of the United States, Jennifer Brown (Diane Lane), and the other, Regina Oliver (Jennifer Wigmore), who has a constitutional claim to the presidency—are meeting for the first time. Oliver recently woke up from a life-threatening crash while visiting Tel Aviv and is being pushed in a squeaky wheelchair underneath harsh fluorescent lights. The music fades, giving an almost clerical air to this tense performance of polite-white-woman politicking.

Oliver is dressed like a bourgeois patriotic trucker—the liberal media’s ruralish image of a pro-presidential Pumpkin draped in faux fur and cop sunglasses. We hear President Brown’s heels attacking the linoleum before we see her emerge from the shadows. A smile forces its way across the side of her face as she begins to applaud—cueing the rest of her team: “Yes, it is time to clap”—the return of her political rival. She nods as she approaches the wheelchair and extends her hand to Oliver, who returns the president’s fake smile. “We’re so glad you’re home,” Lane says with a perfect grin-grimace. Oliver then lifts up her right arm, dramatically revealing a deep abrasion to her that makes the onlookers audibly gasp. It wasn’t totally clear whether the scene was supposed to elicit the chest-chuckle it did—the majority of the show’s tone is rather grave seriousness—but the level of posturing in a podunk corner of the ancient, ruinous house just screamed, “This is what second wave white feminism brought us.”

All throughout, Oliver, the hobbled right-wing extremist, is beaming, knowing that she’s thrown a wrench in Brown’s tragic coup. This scene features all the elements of what the show is attempting to do: complicate the idea that patriarchy dies with the patriarchs, tell a bleak tale about the tragic resiliency of personal ego in the wake of massive catastrophe, and unpack the personalities and powerful forces circling main character Yorick Brown (Ben Schnetzer). But with such a focus on the political machinations and social contexts existing both in and outside the world of Y: The Last Man, it seems like producer Eliza Clark shied away, whether due to budget constraints or otherwise, from the more enjoyable aspects of the OG material.

The original design of Brian K. Vaughan and Pia Guerra’s science-fiction series was set over vast wastelands and deserted highways to actual sand-covered swaths that seemed to go on for miles beyond the panels. While the show feels confined to very static spaces—the broken-down White House, shoddy, shadowy homes of a few characters that ultimately fade away into the bleak abyss, a nondescript cleaner’s shop that houses an East Asian family and, at one moment, Yorick, who stomps through the sewers in search for a frightened Ampersand. But these dreary set designs have no thematic connection, and are not individual enough to denote any real tonal changes. Even the introduction of certain characters, like the mob of murderous Republicans seen early on in the comic—who will be central to the show beyond the six episodes critics were given access to—are only gestured toward, never seen at their peak powers. I have no doubt that they will show up later, but their handling in the novel is both ominous and comedic in equal measure, which the show almost never quite hits early on.

Y: The Last Man is a perfect example of balance being an issue of both pacing and atmosphere. The narrative jumps character to character—from Yorick and his secret agent escort, 355 (Ashley Romans) finding their way to the White House to Amber Tamblyn’s hearty performance of right-wing talking head Kimberly Cunningham jousting with the lower dregs of the political realms to gain more leverage on the president, to Yorick’s sister Hero’s contentious personality and the ways her friend Sam opens her up to possibility. The ensemble here is a sprawl of talented folks monologuing their adjustments through a completely different social order.

Unfortunately, we don’t have any clue about how that social order has dramatically changed (at least not in a way that feels immersive). From the quick-talking political quips in the relative safety of the White House, we’re told of the damage to New York City, the radical extremists who are circling the perimeter, and how the decision to close a highway or cut off electricity is impacting people. But we never see it. As bleak as the colors are—damn near Jessica Jones-levels of darkness—we never feel the deprivation. We don’t know the kind of world that surrounds these characters, only that it is one worth saving.

The first few chapters of the graphic novel were a master class of world-building in order to tell us about the characters that live within it. Early on in the comic, Yorick is captured by a woman driving a dumpster truck filled to the brim with rotting corpses. The CDC is doling out one can of food per corpse and before she learns that Yorick is a man, she offers him a share of the profits if he helps to put them in the back. When his gender is revealed, she gropes him in disbelief and handcuffs him to the back of the dumpster. “What are you going to do, rape me?” Yorick asks. “Don’t flatter yourself,” she answers, “I’m going to sell you.” In this chance altercation we learn a number of things about the material world: that the government is offering rations, food cans are the new currency, and (most crucially to the aims of the show) that women can and do exercise violent commodification when the conditions are favorable for them.

We don’t really have that fleshed-out world here, only one that we are already supposed to know exists. But the inclusion of various characters on different points of the experiential and political spectrums gave life to the graphic novel; a vibrancy that is simply missing from the new version. Leaning into the political underpinnings of the source material (no one can argue in good faith that the show is unnecessarily political) as its sole focus does seem to skimp over the vast constellation of stories that kept audiences engaged for six years.

In 2019, sitting on a panel at New York Comic Con, the creators of the apocalyptic graphic novel Y: The Last Man, writer Vaughan and penciller Guerra, were asked to look back at their 2002 subcultural hit about the last male human (and monkey, Ampersand) to survive a global extermination of all Y chromosome’d mammals. They were pressed on two crucial questions that, in our own sort of retrospective, unlocked the limits and accomplishments of the new FX on Hulu show based on the novel.

The first was about how to create popular comics for the uninitiated. Vaughan praised Guerra for the ease of access, the cleanliness of the layout, given how gregarious and gross comic-book bodies were in the ’90s, with oversaturated colors enveloping the panels in unnecessary mess. Guerra said it simply: “clarity.” Perhaps her sensibility toward comics as a woman who wasn’t always the primary target for the brash masculinity of the ’90s had mellowed her to some of the brutish standards of the period.

But the second, more dubious answer regarding the long-tenured comic heads came from Vaughan. When asked what he’d change about the comic if he made it nearly 20 years later, he responded: “I thought about going back and George Lucas-ing it up but honestly I wouldn’t change a thing; it was a product of its time. That being said, if it was created today it would probably be more ‘woke.’” One could imagine that the OG material probably would’ve been absent a number of casually tossed R-word bombs, one specific usage of “n--ga,” and include more fleshed-out arcs exploring the dynamic experience of transness in a world like this one. What’s missing most isn’t the social awareness but the clarity of what it was about Y: The Last Man that really touched people. It wasn’t the political intrigue—though there were loads of it— it was about the ambitious turns, the twists that flooded every chapter, and the long-term development of Yorick and his crew to figure out what the hell is going on both in the world and within themselves.

It’s fascinating that the adaptation of a variety of comic book material has still resulted in a familiar drab look. In his piece in The Verge, Andrew Liptack wrote about what felt, at that point in 2017, like the high-point of Hollywood adaptations of novels. Speaking to Hawk Otsby (co-writer of Children of Men and producer of The Expanse) about why studios are more likely to go for well-trodden intellectual property, he explained, “It’s all about managing risk for the studios. Audiences know the story, so they’re sort of pre-sold on it. In other words, it has a recognizable intellectual property and can rise above the noise and competition from the internet, video games, and Netflix.” The big red company looms large in the sameness of comic book and graphic novel adaptations. Because the budgets for these products aren’t huge, corners are cut in lighting and action sequences to the point where it’s very hard not to look and sound like a Netflix adaptation project like Umbrella Academy or the aforementioned Jessica Jones. Y: The Last Man is a perfectly serviceable political thriller, but the comic-book trappings that really made the panels sing just aren’t present here.

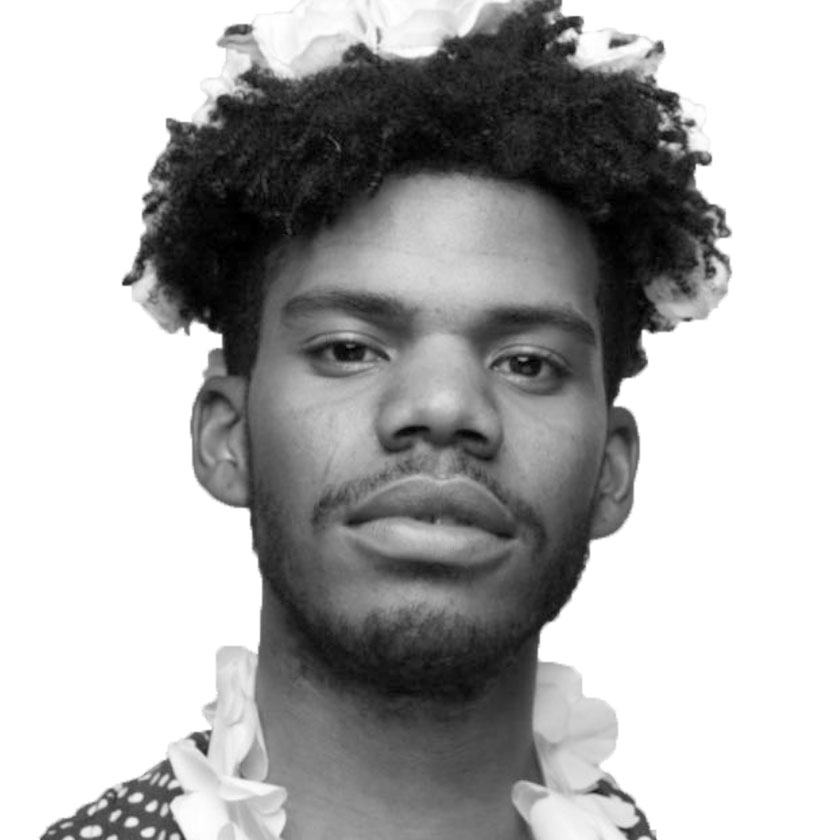

Vaughan wasn’t wrong, as the new show emerging from the FX oven—which stars Ben Schnetzer as Yorick Brown—is indeed a lot more conscious of the gender spectrum’s varying degrees and includes (gasp!) a real life trans person—Elliot Fletcher—playing (gasp!) an actual trans character. We’re happy to say that no genders were harmed in the filming of this show, and that nothing went up in flames. But there were more gut-testing choices that weren’t taken; choices that have more to do with world-building that leaves the small-screen version of Y: The Last Man feeling a little boneless.