With viral hashtags like #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen and #DropDunham, it’s easier than ever for activists to finally make headway against feminism’s traditional allegiance to white, straight, cisgender, and non-disabled women only.

After the Isla Vista shootings in May, the Internet responded by sharing thousands of stories with the hashtag #YesAllWomen, making it clear that every woman faces daily harassment and discrimination. But despite the campaign’s many victories, the hashtag also made clear that #YesAllWomen is really just for some of them.

When Stephanie Woodward blogged about #YesAllWomen, she was excited to join the movement and share her own life experiences as a woman with a disability. She never expected her post to spawn hostile messages from activists scolding Woodward for trying to “detract from the real issue” and instead make it about disability.

“I didn’t know that talking about the violence that women with disabilities experience detracted from whatever the ‘real issue’ is,” Woodward says. “Do women with disabilities not count as women? Are we not part of your population?”

Woodward’s experience is, sadly, not unique. Feminists with disabilities say their voices aren’t being heard, and this is very, very dangerous. Why? Because women with disabilities are one of the most at-risk demographics in the world. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, a staggering 80 percent of disabled women are sexually assaulted, and the rates are even higher for women with cognitive disabilities. Disabled women are, in general, 40 percent more likely to be violently treated—usually by their male partners, but also by caregivers and family—than non-disabled women.

Part of the problem that’s keeping women with disabilities from participating in feminism is simply a lack of physical accessibility. Too often, the local feminist group holds its meetings in an upstairs coffee shop with no elevator or a crowded bar with no hearing loop, effectively keeping out anyone with a physical difference. Most of the time, it’s a lack of funds that’s to blame; that hard-to-access pub let’s the group meet for free on Thursdays, whereas the fully accessible meeting hall charges a pretty penny.

But when it’s not physical accessibility, it’s a lack of empathy or understanding that excludes disabled women. Beneath a blog post on The F-Word, a feminist website based in the UK, several commenters acknowledge that engaging in feminism when you have a disability is more trouble than it should be. One commenter says that while she’s physically able to access her local group’s meetings, the fact that she needs her caregiver to tag along is the real problem. “My carer is my boyfriend, and I need to be accompanied by him in most places,” she writes. “Every local feminist activist group I have found so far has stated that its meetings are open to women only. If my carer can’t attend then I can’t attend and that’s that…While I understand why they restrict entry, I feel that there should be some flexibility where disabled women are concerned.”

This lack of understanding that so many mainstream feminists show can even merge into an all-out dismissal of the very oppression disabled women face: ableism. “When it comes to intersectionality, it seems that many feminists simply forget that disability and therefore ableism are issues which feminists should care about,” says Elsa S. Henry, who runs the popular blog Feminist Sonar. Henry says she’s been actively shoved out of feminist discussions after pointing out the ableism present. That’s not surprising, considering the number of pop culture feminists who personally engage in ableism themselves. For instance, English writer and critic Caitlin Moran lost some fans after she described her teenage self as having “the joyful ebullience of a retard” in her 2011 memoir. (She also made marginalizing comments about transgender people and intersectionality as a whole.)

“When feminists align themselves with ableist role models and refuse to accept that there is something wrong with the way that they treat people with disabilities, it further stigmatizes and erodes the ability of disabled feminists to function,” Henry says.

Things get even more heated when feminists with disabilities address the issue of reproductive rights—one of the mainstream movement’s biggest issues. While the majority of disabled activists I spoke to identified as pro-choice, they felt deeply conflicted over some of the arguments that feminists use to justify legalizing abortion. “Every time that we see abortion policies in the news, someone inevitably brings up the fact that abortion should be legal so that people can abort their disabled babies,” Henry says.

“Reproductive rights is a complex issue for people with disabilities,” says Allie Cannington, a youth disability organizer and co-founder of the project #DisabilitySolidarity. “While disability rights and justice activists ground their work in self-determination and bodily autonomy, issues…can get convoluted when abortions still take place to solely eliminate the fetus based on disability.”

The same goes for forced or coercive sterilization of women with disabilities, which is more common than people realize. “You would never hear any woman—any feminist—say, ‘Yes, it’s okay for a parent to have their daughter forcibly sterilized,” Woodward says. “But suddenly, when it becomes a daughter with a disability, there’s so many people saying, ‘Well, you know, there must be a good reason for that,’ or ‘I could see why that would that happen.’ You don’t get the same amount of outrage.”

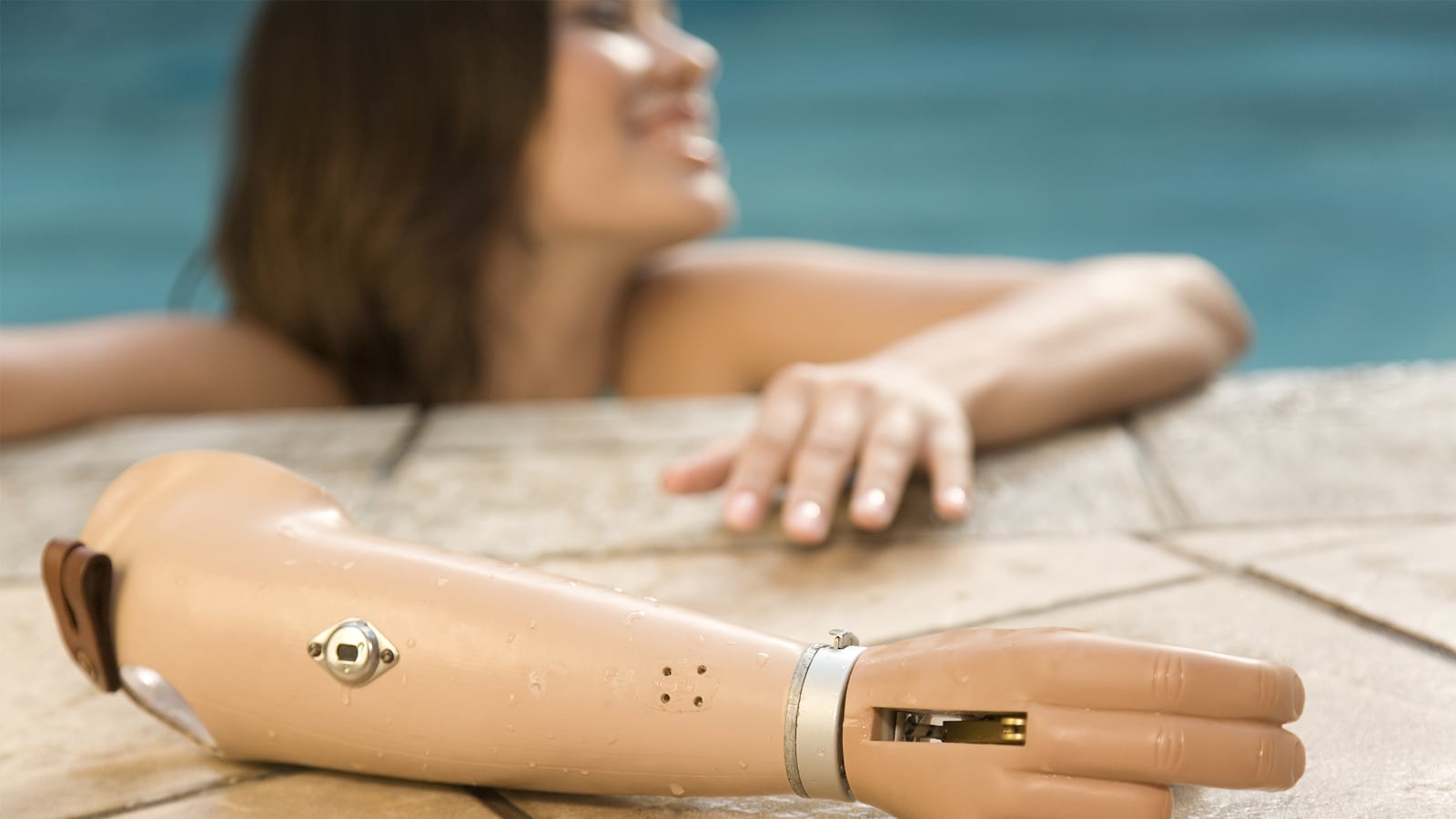

There are currently more than 27 million women with disabilities in the U.S. alone, and the numbers are rising. Anyone can acquire a disability at any time, and the wrongs that women with disabilities feel are wrongs that you could one day feel as well.

“Non-disabled feminists really need to examine their own privilege and ableism and listen to what disabled women are saying,” says Caitlin Wood, a writer and editor. “Because we're here, and we've been here forever trying to get people to pay attention.”