After five days of presenting evidence, plaintiff E. Jean Carroll rested her rape case against former President Donald Trump Thursday. It was yet another bad day for Trump.

The proceedings began with the jury hearing more damaging portions of his deposition. Later, former local news anchor Carol Martin took the stand and corroborated Carroll’s testimony that she had told Martin about being raped by Trump shortly after it happened. Finally, Carroll presented an expert witness on publicity, who testified that Carroll would have to spend approximately $2.7 million to purchase the media time that Trump’s disparaging comments about her received.

Immediately after Carroll rested her case, Trump’s attorney, Joe Tacopina, did likewise—without presenting any evidence or witnesses.

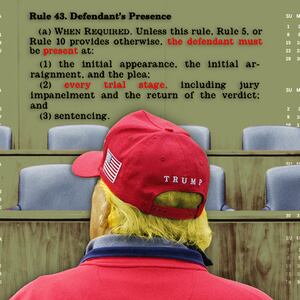

Trump, meanwhile, continued to attack the trial from afar, weighing in from a golf course in the UK. The former president claimed he would cut his golf trip short to “confront” Carroll at the trial, which he called a “disgrace.” Tacopina, however, told the Court that Trump would not attend and would not testify.

Judge Lewis Kaplan, who noted that Trump had said something directly contrary, is giving the former president one final chance to change his mind—allowing him to make a motion to testify by 5 p.m. EDT on Sunday.

Deposition Excerpts Continue to Pummel Trump

When Trump testified at his deposition in October, many people predicted it would go badly for him. It went even worse than the most dire predictions.

I did not think that the Access Hollywood tape—where Trump stated that he could “grab them by the pussy” because he was “a star”—could get worse for him, but it did. When asked about that quote, however, Trump defended it, stating “Historically that’s true with stars. If you look over the last million years, that’s largely true, unfortunately—or fortunately.”

Perhaps the worst part of Trump’s deposition was that he repeatedly identified the woman in a picture with Trump and his first wife, Ivanka as his second wife, Marla Maples. One time he stated, “It’s Marla” and the second time, “That’s Marla, yeah. That’s my wife.” In fact, the woman he called “Marla” was the plaintiff, E. Jean Carroll. Under any circumstances, this gaffe would have been damaging: that Trump was not prepared to answer questions on the only meaningful photograph in the case is astounding. But given the fact that Trump has focused his defense on the claim that Carroll was “not his type,” the fact that he could not distinguish between Carroll and Marla Maples—a woman he found so attractive that he had a torrid affair during his first marriage and eventually married—is devastating. I expect Carroll’s attorneys to return to this theme in their closing arguments.

The jury also heard Trump’s demeaning deposition testimony directed at Carroll’s lead attorney, Roberta Kaplan. When Ms. Kaplan asked Trump what he meant when he said that Natasha Stoynoff (who accused Trump of sexual assault at Mar-A-Lago in 2006) “wouldn’t be my first choice,” Trump turned his fire on Ms. Kaplan, saying, “You wouldn’t be my first choice either.” My experience in more than 25 years as a trial attorney (including trying a case against Ms. Kaplan) is that jurors do not like it when someone makes a personal attack on one of the attorneys. On a related note, I am confident that both Ms. Kaplan and her wife were happy to learn that Trump was not attracted to her.

Local News Legend Corroborates Carroll’s Testimony

When I was growing up in New York during the 1970s and 80s, Carol Martin was a local legend. She was the co-host of the CBS affiliate’s evening news at 5, 6, and 11 p.m. She was the first African-American woman to anchor a newscast in New York. She was always poised, even-tempered, and even-handed. I have to believe that the four jurors (out of nine) who are older than 50 have similar memories.

Martin’s testimony corroborated the most important portions of Carroll’s testimony. Martin said she specifically recalled that Carroll told her she had been sexually attacked by Trump. Martin further testified that Carroll said she already told Lisa Birnbach, who advised Carroll to go to the police and make a complaint. Martin testified that she advised Carroll not to go to the police because “Trump has a lot of attorneys and he would bury her.”

During direct questioning, Martin admitted that she did not like Trump or his politics, but that the reason why she was testifying was “to recount what my friend told me in 1996. I believed it then and I believe it now.” (Judge Kaplan sustained an objection to the “I believe it now” part of the answer.)

The Trump team’s cross-examination of Martin made virtually no headway. Martin admitted she sent a text message deriding Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump as “junior grifters”—but I cannot imagine a New York jury disagreeing. When Tacopina asked Martin what Carroll meant when Carroll texted her, “I have something special for you” (which he insinuated was about the accusations about Trump), she responded, “I think she was referring to the stuffed squirrel she gave as a gift.” Tacopina was taken so aback that he asked, “When did you think of that?”

During this cross-examination, Tacopina again raised the ire of Judge Kaplan. Departing from appropriate protocol, Tacopina began reading from Martin’s deposition. When Judge Kaplan interjected, “Please get to the question,” Tacopina talked back, saying “I’m just setting it up.” Judge Kaplan responded, “Questions, not setting up. We’re not setting up in a restaurant.” Tacopina meekly abandoned the whole line of questioning.

Tacopina was not done being scolded by Judge Kaplan. When Tacopina made a snide comment to Martin, which he tried to turn into a question, Judge Kaplan disallowed the question, calling it “argumentative.” Perhaps because Tacopina previously moved for a mistrial based upon earlier rulings by Judge Kaplan that Tacopina’s questions were “argumentative,” the judge responded by reading the definition of “argumentative” from Black’s Law Dictionary to Tacopina in front of the jury. In my experience, the jurors likely took that exchange as major commentary on Tacopina’s trustworthiness.

Media Expert Quantifies Carroll’s Damages

Carroll’s expert witness on defamation damages, Professor Ashlee Humphreys of Northwestern University, placed a price tag on some of the damages that Carroll is seeking in this case. Humphreys testified she had analyzed the publicity generated by 17 out of the 60 statements by Trump that Carroll has contended in her complaint were defamatory. For those 17 statements, Humphreys calculated how much it would cost for Carroll to purchase time on television and social media to generate the same amount of publicity for a counter-message of “reputation repair.” She testified that it would cost as much as $2.7 million.

This calculation was the first time that anyone has attached a dollar figure to any portion of Carroll’s claim for damages. “Reputation repair” might be the smallest part of Carroll’s damages, which also include (a) the physical and emotional damage from being raped by Trump, and (b) Carroll’s loss of income from his defamatory statements after she accused Trump of rape.

There was no meaningful cross-examination of Humphreys, as the objections to most questions by W. Perry Brandt (another member of the Trump defense team) were sustained.

Only Closing Arguments Remain

Closing arguments are the only thing left for the jury to hear in this trial and will be presented Monday. Each side will be given two-and-a-half hours.

Carroll’s attorneys will go first, with a two-hour block starting at 10 a.m. and going until noon. After a lunch break, Trump’s attorneys will have from 1-3:30 pm. Finally, Carroll’s attorneys will have 30 minutes for “rebuttal” from 3:45-4:15.

I expect that Judge Kaplan will instruct the jury on Tuesday morning, after which they will go to the jury room to deliberate. At some point after that, we will learn what the jury thinks of all of this.

Although it appears to me that this trial has largely gone as well as Carroll might have hoped, I am not going to be so foolish as to make a prediction about what the verdict will be or when it will come.