There’s a sickly-sweet Scottish soda I love called Irn-Bru. It’s hard to find in the U.S., so when I have a craving, I go to Amazon and order a six-pack that shows up on my doorstep a few days later.

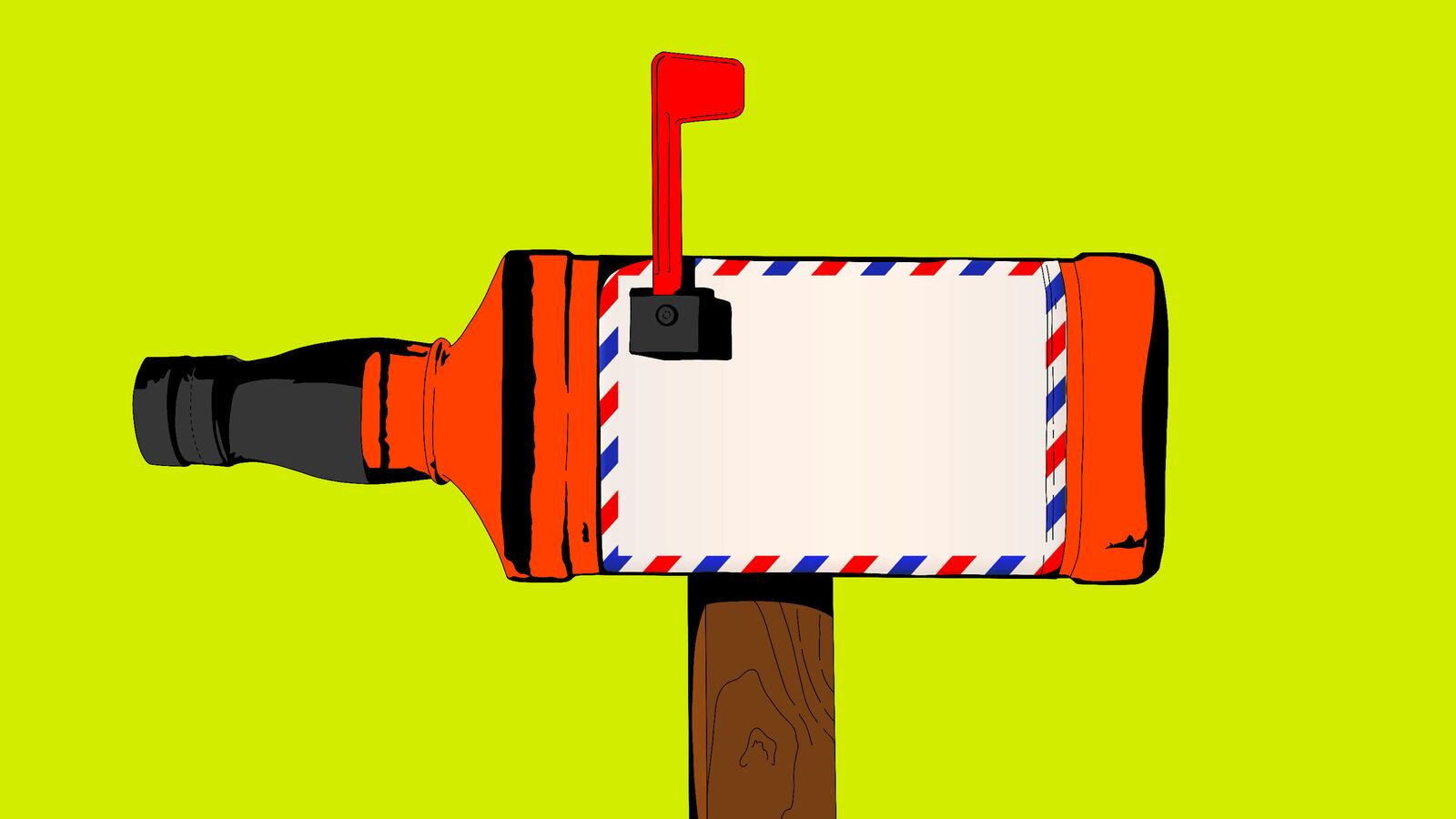

While you can order almost any beverage online nowadays and have it shipped to you, there’s one glaring exception: alcohol.

In most of the U.S., the only way to get a delivery of your favorite whiskey, rum or tequila is to place an order through a local store, often using a third-party app like Drizly or an online storefront like ReserveBar. Services like these may appear to operate a central warehouse, but are actually a façade for retailers, which fulfill orders as they come in.

This isn’t the case elsewhere in the world, but the U.S. has a unique alcohol regulation system—51 of them, actually, for each state and Washington, D.C. The passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933 ended national Prohibition and allowed each state to set its own laws about the production, sale and distribution of alcohol. There was just one across-the-board mandate: no state could transport alcohol to another state in violation of the latter’s laws. Because each state makes its own rules, stores and distributors—which act as the middlemen between retailers and distilleries, wineries, and breweries—have to obtain unique licenses and meet different regulatory requirements wherever they operate.

So, despite the fact that, once upon a time, you could get liquor through the mail, nowadays a store in Manhattan can’t even offer delivery across the Hudson River to Jersey City, regardless of proximity.

When it comes to spirits, right now you’re pretty much stuck with what’s available in your area. But there might be some hope that this situation is changing. Ten states and Washington, D.C., currently allow local distilleries to ship bottles right to residents. While the list is modest, the state that joined most recently—Kentucky—could hold the key to changing how all Americans buy liquor.

Last year, Kentucky’s House Bill 415 passed and as a result distilleries (and importers) within its borders can ship spirits directly to adults anywhere in the state, as well as to other areas with reciprocal agreements. (Distillers and importers in those markets can likewise ship to consumers in Kentucky.)

While a few craft distillers in Kentucky were quick to offer so called direct-to-consumer (DTC) shipping, the state’s biggest players have taken a bit of time to work out how best to proceed. But this past summer, Maker’s Mark and its sibling the James B. Beam Distilling Co. launched DTC options for whiskey fans.

“Here’s something special on your doorstep, a unique release, and then [we] bring it to life with storytelling,” says Rob Samuels, managing director of Maker’s Mark. “DTC provides us just a new way to bring the distillery and some of the very personal, authentic experiences alive for folks that can’t always make it [in person].”

Offering mainly special-edition whiskies and currently limited to just a few hundred members, the Maker’s and Beam programs closely resemble the DTC wine clubs that have existed for decades in California and other parts of the country. Currently, 46 states and Washington, D.C. allow DTC shipping of wine.

Why can wineries ship directly to consumers in more states? The short answer: “wine whined first,” says Margie Lehrman, CEO of the American Craft Spirits Association (ACSA), quoting a state regulator she once met.

The ACSA strongly supports opening up DTC shipping for distilleries, as do the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) and the American Distilling Institute (ADI). These three organizations represent the more than 2,200 distilleries currently operating in the U.S.

Chris Swonger, president and CEO of DISCUS, sees a lot of value in states allowing DTC shipping and thinks it will actually aid the country’s traditional distribution system. “It will help [a distiller] grow the brand, and then that enables them to be better positioned to partner with great distributors,” he says.

Westward Whiskey, based in Portland, Oregon, is trying this idea out with its club, which recently expanded beyond state lines to encompass 28 additional markets. Though club shipments are not technically direct to consumer, and are rather fulfilled via a third-party company, Westward co-founder and CEO Thomas Mooney is in favor of DTC. He says that his club’s goal is to expand the distillery’s fan base with unique one-off bottlings and not to compete with liquor stores selling its core line. “We’re simply taking upon ourselves the work of introducing people to our brand through some of the most interesting things we do,” he says.

DTC shipping allows people to buy spirits that aren’t available locally and boost a distillery’s bottom line. But efforts to expand it are opposed by the country’s distributors, who currently control which brands make it onto retail shelves—a system that can be hard to crack for small and unknown producers. Michael Bilello, senior vice president for marketing and communications at the Wine & Spirits Wholesalers of America, even admits that “there’s currently no solution” for consumers seeking to buy spirits that aren’t available locally. DTC could certainly provide that solution.

Kentucky’s new law gives other states a model to use, especially as more distilleries adopt DTC shipping in some fashion. An informal poll of 16 distilleries in the Bluegrass State, including all of its major players, showed that five were already shipping DTC and another seven were discussing or actively planning for it.

A similar bill to the one passed in Kentucky is currently in the works in California and could be a huge game-changer, given the sheer size of that state. Passage of the bill would allow in-state and out-of-state distillers (plus in-state importers) to ship spirits right to the door of tens of millions of California adults. Wineries, of course, have already enjoyed these privileges since the 1980s.

“This is a country that was built on choice,” Lehrman says. “We see [DTC] as the next phase in the growth of the industry that allows the consumer really to continue to choose, as they do with everything else in their lives.”