A rising wave of extreme anti-Shia sectarian violence is sweeping Iraq. Hundreds have died in terror attacks this summer. The mass slaughter of Shia at the hands of al Qaeda threatens to drag the country back to civil war. Worse, al Qaeda in Iraq has now exported its violence to Syria, and Lebanon is not far behind. Not since the Saudi and Wahhabi sack of Najaf and Kerbala in 1806 has sectarian violence in the Middle East been this extreme.

The origins of this wave of extreme sectarianism are many, and Iraq’s Shia government cannot escape much of the responsibility for allowing it to develop. Prime Minister Maliki’s government encouraged Shia identity and sectarian animosity. Sunni Arabs have been treated poorly. Iran has encouraged Maliki’s sectarian policies at home. The Iranian and Hezbollah intervention in Syria this spring has exacerbated the tensions to the boiling point.

But al Qaeda is the principle culprit. Its Jordanian founder, Ahmad Fadil al Khalayilah, (better known as Abu Musaib al Zarqawi) was called inside al Qaeda by his other nickname, al Gharib, or “the stranger,” because his sectarian views were extreme among extremists. Zarqawi elevated violence against the Shia of Iraq to levels not seen in the last two centuries.

Beginning in 2003, Zarqawi targeted Shia leaders, Shia mosques and shrines, and Shia holy days for extreme acts of violence. Zarqawi likened his hundreds of Shia victims to be modern-day Safavids, after the Shia dynasty that made Iran a Shia state, and saw himself and his al Qaeda gang as reaping grim justice on Shia “heretics.” Zarqawi never made any secret that his real target was the Safavid heartland itself, Iran.

The American surge was supposed to crush al Qaeda in Iraq. Zarqawi was killed after a long man hunt. But Zarqawism outlasted Zarqawi. Indeed, it has grown stronger since his death. Gen. Stanley McChrystal, who brilliantly led the hunt for Zarqawi, has said it came too late. The genie was out of the bottle.

Today, Zarqawi’s successor, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi (a nom de guerre), aspires to outdo his mentor. He orchestrated the massive attacks on two prisons in July that freed hundreds of al Qaeda terrorists. Baghdadi, also called Abu D’ua, has announced al Qaeda’s front group in Iraq had been expanded to be the Islamic State of Iraq and al Shams. Al Shams means greater Syria—that is all of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel.

Baghdadi has announced he has taken on the leadership of al Qaeda throughout the Fertile Crescent, noting rightly that Osama bin Laden gave Zarqawi all that turf back in 2004 when he anointed him al Qaeda’s commander for the entire region. Baghdadi is eager to export his violence into Lebanon, taking Hezbollah on in its own backyard.

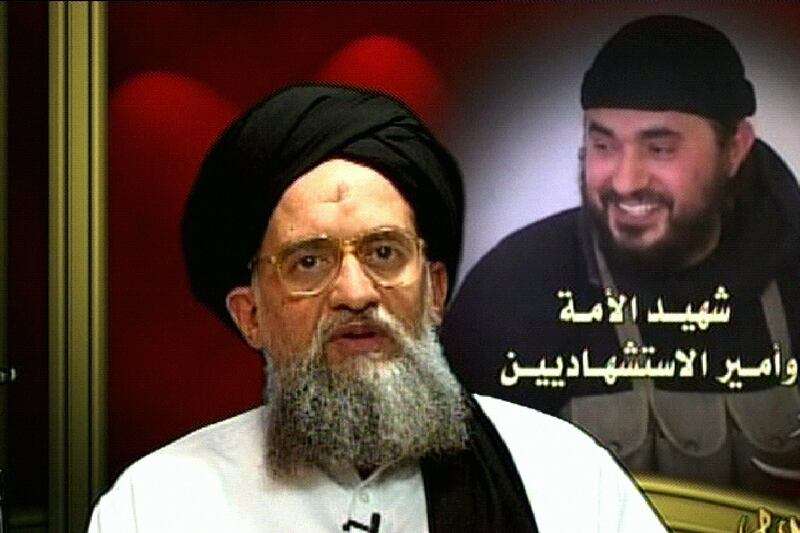

The Syrian Mohammad al Golani, who is the leader of al-Nusra Front, worked with Zarqawi in Iraq a decade ago. His group initially tried to play down its sectarian nature in Syria somewhat but now it uses all the symbols of Zarqawi, including his flag and much of his rhetoric about Iran and Hezbollah. Sunnis from across the Arab world are flocking to al-Nusra’s banner. Dozens of Saudis, Tunisians, Libyans and Jordanians have already been martyred in the Syrian civil war fighting for al-Nusra. Golani proclaims that he is independent of Baghdadi and reports directly to al Qaeda’s amir in Pakistan, Ayman Zawahiri, but on the ground the two al Qaeda groups increasingly cooperate.

The State Department this weekend said Baghdadi has now transferred his base into Syria, probably to make it harder for the Maliki government to find him. There is a $10 million U.S. reward for information that leads to his arrest or killing. But the violence in Iraq is only likely to get worse even if Baghdadi was found and eliminated. Al Qaeda in Iraq has proven it can survive decapitation more than once. Nonetheless, al Qaeda cannot take over Iraq. It is a minority in a minority. It appeals to angry Sunni Arabs who are less than a third of Iraqis. It can create chaos and terror but not a Sunni return to power in Baghdad.

The regeneration of al Qaeda in Iraq and its expansion into Syria is a warning to American decision makers. Few al Qaeda franchises or associated movements have ever been permanently destroyed. They can be disrupted and dismantled and yet fully regenerate once the pressure subsides. The same is likely to happen in Pakistan and Afghanistan if the NATO transition after 2014 does not include a robust counterterrorism capability to target al Qaeda in South Asia.

Zarqawi’s legacy is now very deeply rooted in the jihadist movement that is exploiting the breakdown in law and order across the Islamic world and especially the Arab world this century. His fierce ruthless determination to kill Shia will not vanish any time soon. Zarqawi is admired across the global jihad from Algeria to Baluchistan for his extremism. America’s misguided war in Iraq may have finished for Americans, but its violent backlash is far from over.