The 10th anniversary of 9/11 is painful in two ways. It is painful, obviously, because it makes us contemplate those Americans who died. But it is also painful because it makes us contemplate America itself, a nation that has grown far weaker in the decade since that terrible day.

It was not supposed to be this way. In 1951, on the 10th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Americans could look back with satisfaction on their victory in World War II and America’s emergence as the most powerful nation on earth. In 1989, on the 10th anniversary of the Iran hostage crisis, Americans could look back upon our victory in the Cold War. Today, by contrast, we have descended into two costly and unnecessary wars, a brutal recession, and a highly vulnerable position on the international economic stage.

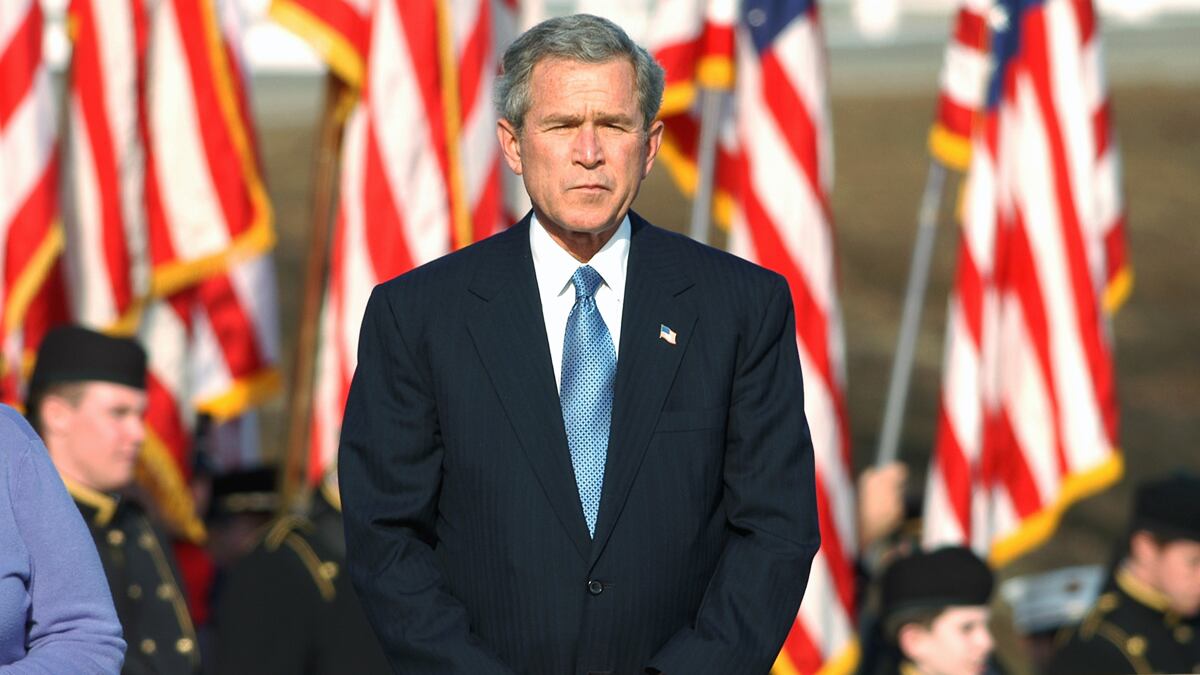

The man most responsible for this trajectory, George W. Bush, will be on hand with Barack Obama for the memorial service. Bush’s central error, in retrospect, was conflating 9/11’s human significance with its geopolitical one. In human terms, 9/11 was one of the singular events in American history. In terms of sheer human pain, no other day in America’s recent past even comes close. It was perhaps natural, therefore, that Bush would see 9/11 as geopolitically momentous, too. But, in fact, it was not. The defining geopolitical reality of our time was, and is, the shift in power from America and Europe to Asia, a shift with profound consequences for the way Americans live their lives. But Bush never grasped the enormity of this shift, and the way in which it would challenge America’s preeminence. Around him were advisers like Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz, who had spent their careers around the Pentagon and assumed that America’s great post–Cold War challenge would be military. And Bush himself, while looking for a grand purpose for his presidency, was unable to find it in the quiet, complex drama of shifting economic power.

Instead he treated 9/11 like it was Pearl Harbor: the beginning of a global war against a 21st-century Nazi Germany and Soviet Union rolled into one. Bush assumed that if al Qaeda could kill 3,000 Americans on one day, it could kill 30,000 or 300,000 on another. And he assumed that Salafist-jihadist ideology was among the most important political phenomena in the Muslim world. But al Qaeda had pulled off 9/11 only because the United States had been asleep at the wheel; once the entire world began worrying about jihadist attacks, large-scale jihadist attacks dropped dramatically. And as the Arab Spring now makes abundantly clear, al Qaeda is as weak ideologically as it is militarily. It is mostly irrelevant to the great struggles in today’s Middle East.

Obama’s challenge today—and from now on—is to delink the emotional crucible of 9/11 from the broader American foreign-policy debate. Sept. 11 was a human enormity produced by a network that, geopolitically, isn’t that important at all. If the man flying from Texas to Ground Zero this weekend had understood that better 10 years ago, we’d be a stronger country today.