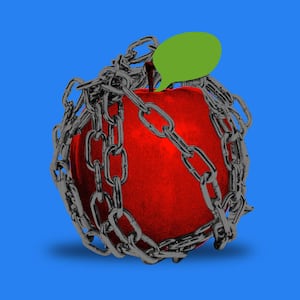

We’re in the midst of a legislative war on American education. At the heart of this conflict are educational gag orders—state legislative attempts to restrict teaching, training, and learning in K–12 schools and higher education.

These bills, which generally target discussions of race, gender, sexuality, and U.S. history, began to appear during the 2021 legislative session and quickly spread to statehouses throughout the country. By the year’s end, 54 bills had been filed in 22 states, of which 12 became law.

These battles have since intensified in 2022.

ADVERTISEMENT

My organization, PEN America, recently released a report on educational gag orders in the 2022 state legislative sessions. Since the start of this year, we’ve tracked a total of 137 educational gag order bills introduced in 36 different states. The number of bills has increased 250 percent compared to 2021. And the bills have tended to be more punitive, to target more types of educational institutions, and to restrict a wider array of speech.

Only seven new gag order bills have become law so far this year, but these include some of the most censorious laws to date. Nineteen states, home to 122 million Americans, now have some sort of educational gag order on the books. The entire year can be summarized in a single word: escalation.

And things are about to get even worse.

For one thing, more educational gag orders seem almost certain to be introduced next year, particularly in states such as West Virginia, where lawmakers missed by four minutes this year’s deadline to pass a gag order bill, and Arizona, where a gag order failed because a single lawmaker was absent. And gag order bills that specifically restrict speech around LGBTQ+ issues and identities—such as Florida’s censorship law, dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” by critics—also seem likely to become more common in 2023.

But even in states that already have educational gag orders on the books, new types of censorious legislation are on the way.

One likely focus of new bills will be to make existing gag orders more punitive. Wade Miller, executive director of Citizens Renewing America—a conservative advocacy group that serves as a clearinghouse of model educational gag order legislation—recently opined that all gag orders should have a “mandatory enforcement mechanism.” Not all currently do, but new proposals may seek to change that. Some bills may also add tip lines for citizens to report alleged gag order violations to the state, similar to the email tip line created by Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s office earlier this year.

Other bills may attempt to expand censorship beyond educational gag orders to more creative attacks on classroom speech. At the K–12 level, many states have seen the introduction of so-called “curriculum transparency” bills that—while they may initially sound reasonable—have in practice often amounted to a kind of surveillance of teachers; legislators may well redouble their efforts next year. Another type of bill likely to see wider introduction are “book ban bills,” such as Florida’s HB 1467, that make it easier for parents to get books removed from school libraries.

Higher education—the subject of over half of the gag orders that became law this year—will likely also remain a prime target. Texas seems poised to lead the way. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick pledged in February to end tenure for all new public university professors and to revoke it for tenured faculty who teach critical race theory—part of a proposal for next year’s legislative session that would enact the most draconian restrictions on tenure, academic freedom, and shared governance anywhere in the country.

More broadly, the battle for public education may be moving beyond state legislatures to local school boards. The CRT Forward Tracking Project at UCLA Law School has documented hundreds of district-level educational gag order measures on instruction related to race. Other district policies have restricted LGBTQ+ identities in troubling ways. In a recent example, the Grapevine-Colleyville district in Texas enacted an educational gag order, a “classroom transparency” policy, a “Don’t Say Gay” policy, and a series of provisions facilitating book bans, along with many other restrictions.

Finally, we are beginning to see a shift from passing new laws to enforcing existing ones in particularly censorious ways.

Some of this over-enforcement has already been attempted through outside intervention. In July, an attorney for the conservative America First Policy Institute tried to force the Baxter Community School District to cancel a planned elective class because of Iowa’s educational gag order, even though all course readings would be selected by students—since the students might choose books that contain prohibited concepts.

In other cases, regulatory bodies have enforced maximal interpretations of gag orders on their own. A few weeks ago, the Oklahoma State Board of Education disciplined two school districts’ accreditation statuses for supposed violations of the state’s law, including one the state department of education later admitted was false. Based on the available evidence, neither district appears to have actually violated the law, but the board proceeded to find them guilty anyway, handing down even harsher penalties than the law called for. In the aftermath, a third Oklahoma district, fearful of being slapped with a similar punishment, disciplined a teacher for telling students about a Brooklyn Public Library program offering digital copies of banned books.

Make no mistake, these attacks on education invite administrative censorship by districts and have a profound chilling effect on teachers and students. According to a new survey by the RAND Corporation, a quarter of teachers nationwide have been directed by school administrators “to limit discussions about political and social issues in class.”

In April, a student at Iowa’s Johnston High School reported that one teacher felt unable to explain the motivations behind the “three-fifths compromise” in the U.S. Constitution without violating the state’s educational gag order. Such strained conditions also seem unlikely to help with the nation’s worsening teacher shortage.

The longer the current campaign of educational censorship persists, the more American students and American democracy will suffer. These trends should alarm advocates of free expression and public education alike.

Jeremy C. Young is Senior Manager of Free Expression and Education at PEN America.