Earlier this fall, the Air Force acknowledged in a little-noticed press release that a virus had affected computers at its Nevada base where many of America’s unmanned aerial vehicles—those famed drones—are operated remotely in faraway war zones. Air Force officials emphasized that the breach did not specifically impact the operation of drones, describing it as “more of a nuisance than an operational threat.”

Now, three months later, government officials are eerily quiet on how a fully operational drone managed to get captured in Iran amid reports the GPS system may have been hacked. Suddenly, America’s vaunted drones—the weapon of choice for spying, killing and tracking U.S. enemies these last few years—seem to have lost a sliver of invincibility and created worries about the vulnerabilities to increasingly curious enemies.

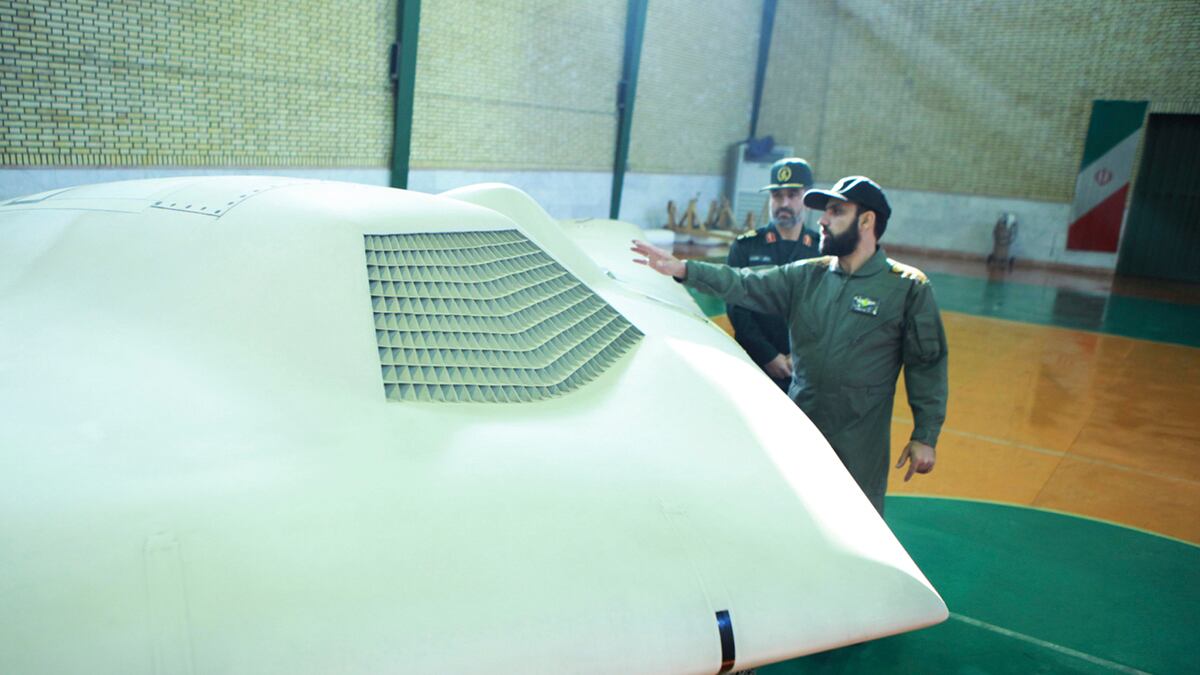

Iranian scientists say that they tricked the CIA-directed drone, a model known as an RQ-170 Sentinel, and forced it to land on their soil, according to The Christian Science Monitor. U.S. officials, speaking only on condition of anonymity because of the sensitive nature of the subject, say that the claims of the Iranians are utterly untrue.

Officials in Tehran and Washington will probably argue for years about what really happened. Still, some uncomfortable facts about the incident are beyond dispute. Michael Toscano, president of the Arlington, Va.–based Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, notes: “A UAV did not perform the way it was supposed to,” using an abbreviation for an unmanned aerial vehicle. “And the bad guys got it.”

This has been a public-relations bonanza for officials such as Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi, who described the drone’s incursion into Iran as a “hostile and aggressive act.”

U.S. officials, unsurprisingly, remain committed to the Sentinel and other drones, regardless of what the Iranians say, but meanwhile some people in this country are wondering if the drones are really as awesome, or flawless, as they have been made out to be.

Ten years have passed since a U.S.-directed aerial drone, gliding over Afghanistan, fired a missile for the first time, and since then the drone has become the most important weapon in the global war against al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

Yet despite its success in taking out al Qaeda leaders in Pakistan, Yemen and other countries, the flaws in the drone program are becoming apparent: insurgents hacked into video feeds from drones in Iraq and Afghanistan a couple years ago; the unmanned aircraft tend to spin off course and crash; and now questions are being raised about the security of their tracking devises.

Security experts say that a new arms race, involving drone technology, is heating up. As Americans increase the deployment of the unmanned aerial vehicles, sending out thousands every year, people in other countries are starting to learn how to take them down.

Air Force officials refuse to speak about “operational” issues in the drone program, and CIA officials refuse to speak about it at all. Nevertheless, the officials will say in general terms that they work hard to eliminate kinks in their operations abroad, and they also say that things are running smoothly.

“We’re obviously constantly looking to identify potential vulnerabilities,” says Lt. Col. John Haynes, a spokesman for the U.S. Air Force, “and when we do see them, we take the most appropriate action.”

They may be taking some action in the future, given the weaknesses that appear to have been exposed in the Sentinel. The main problem lies not with the Sentinel itself or with other drones, say researchers who are familiar with the aircraft, but with their tracking devices: the GPS that they use to navigate rugged lands in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and other places in the world using global positioning system satellites.

The drones apparently use encrypted GPS devices during their flights, and are also outfitted with civilian tracking devices, just in case the encrypted system goes down. That might have been what happened to the Sentinel that landed in Iran.

Like with any technical problem, there is a way to work around it. Drones could operate on their own, without GPS or input from ground commanders, for example. “It’s possible to recognize a mountain on the horizon and then another mountain and then cross-reference it,” explains Kasper Rasmussen, a visiting researcher at University of California, Irvine, who has written about GPS spoofing attacks.

Yet the challenges are immense, and for that reason officials equip the aircraft with GPS tracking devices. “It’s probably the best tool they have available,” Rasmussen says.

When engineers and supporters of the drone program talk about the failure of the Sentinel in Iran, they sound like ... engineers and drone supporters. “You take a look at what went wrong,” the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International’s Toscana says. “Then you look at what measures you need to put in place so it doesn’t happen again.” He also believes that the incident in Iran has an upside.

“It’s like when the oil spill happened in the Gulf, and it caused people to pay more attention to the problem, and after that things got better,” he explains.

Others, too, believe Americans will learn—and in this way benefit—from the incident in Iran. “These problems with GPS are relatively trivial. We will fix it. That’s how innovation happens,” says Missy Cummings, a former U.S. Navy pilot who is now an associate professor of aeronautics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It is the natural course of technological development.”

Not everybody is sanguine. Roger Johnston, the section manager of the Vulnerability Assessment Team at the Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois, helped to demonstrate weaknesses in civilian GPS tracking devises nine years ago in a New Mexico desert. He and his colleagues used a GPS satellite simulator and managed to send GPS signals for more than a mile.

Johnston and his colleagues later wrote papers about the weaknesses in the GPS tracking devices, alerting government officials about the problem and also about the dark scenarios that could unfold. “They just kind of went, ‘Oh,’ and then they said, ‘That’s not very likely,’” he recalls.

Years later, the technological prowess of the drone won over President Barack Obama and administration officials, as well as top-level officials at the Pentagon and the CIA, and they made it into a signature weapon of the Obama White House. That may have been part of the problem. Johnston believes that government officials, as well as engineers, have been so taken with the seductive appeal of the drone that it has blinded them to its flaws.

“Falling in love with your own technology is always a mistake,” he explains. “That’s what they did with the Titanic.”

When Johnston talks about the failure of the Sentinel in Iran, he sounds frustrated. “In my view, this was a total no-brainer,” he says. “If indeed it involves spoofing of civilian GPS, this is jaw-droppingly stupid. I don’t buy the argument, ‘Oh, well, who could have seen this?’ We did.”