First, customs officials seized a crate full of the contraband at the San Francisco port. But that didn’t solve the problem. Some of the banned product had already gotten through and was being distributed on the hard, lyrical streets of San Francisco. So, the authorities had to resort to more extreme measures: an undercover operation to catch the alleged criminals selling the obscene material out in the open. It was a success.

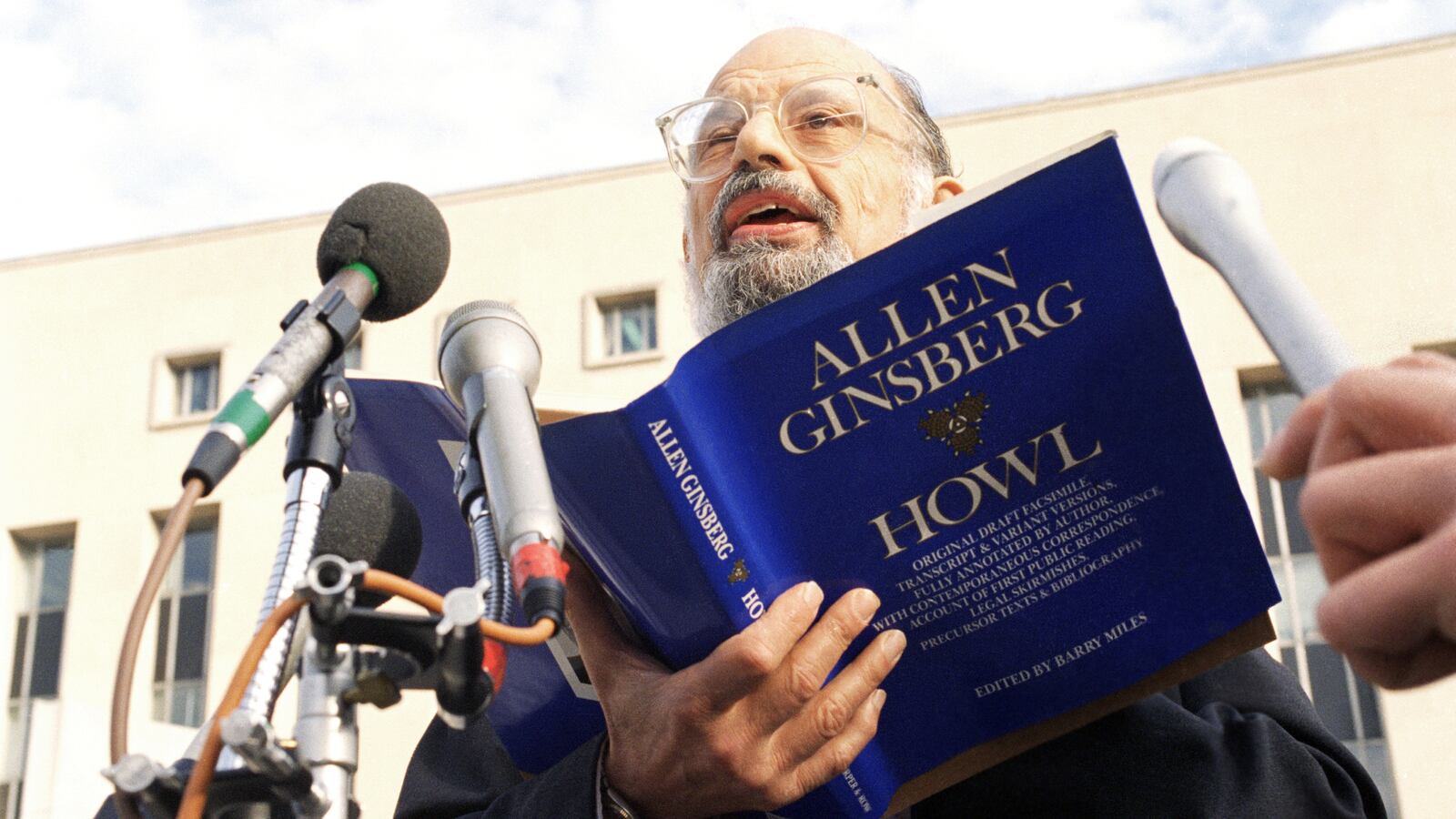

The crime in question, you ask? That would be the sale of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s famed bookshop, City Lights. That’s right—the persona non grata in San Francisco in 1957 was a slim book of poetry.

The origin story of America has one resounding theme: Let freedom ring. Yet, throughout the past 239 years, efforts to curtail said freedom in one of the most banal but insidious ways—telling people what they can and can’t read—have continuously popped up. Book banning is like the ocean; the tide may have gone out, but you can bet it will always come back in again.

Just look at some headlines from this very year: “‘Unparalleled in intensity’—1,500 book bans in US school districts.” “Report Finds ‘Alarming Spike’ in Book Bans in US Schools.” “Efforts to ban books jumped an ‘unprecedented’ four-fold in 2021.”

Clearly, the powers that be learned nothing from the 1957 trial of Howl. In that case, not only did the very conservative judge conquer his own prejudices when he ruled that Howl “cannot be held obscene,” but the notoriety of the trial itself launched Ginsberg’s book into a popularity they may not have been achieved had the law left them alone.

The authorities tried to suppress the brash, vulgar, raw poem-cum-beating pulse of a generation. Instead, they ended up giving it and the entire countercultural movement it helped spawn a totem and rallying cry.

“There was an invitation to experiment”

Ferlinghetti knew exactly how good Howl was when he heard Ginsberg first read it publicly in 1955. “I knew the world had been waiting for this poem, for this apocalyptic message to be articulated,” Ferlinghetti wrote in an essay for Howl on Trial: The Battle for Free Expression published in 2006. “It was in the air, waiting to be captured in speech. The repressive, conformist, racist, homophobic world of the 1950s cried out for it.”

To the burgeoning poet, he sent a more direct and immediate message via telegram: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

By the time a 29-year-old Ginsberg sat down to write Howl, he had already lived a whole lot of life.

Ginsberg grew up in New Jersey, the son of a famous poet and an artistic, Communist mother who struggled with mental health issues. When he was only 21, Ginsberg made the difficult decision to authorize a lobotomy for his mother. He graduated from Columbia University in 1948 despite getting kicked out twice. During his school days, he hung around with the likes of Jack Kerouac, Neil Cassidy, and William Burroughs, as well as a host of characters from the seedier side of the city. He sometimes heard voices.

After graduation, Ginsberg entered the corporate advertising world by day. But by night, he was still hanging out with the rough, avant-garde Greenwich Village crew, which eventually landed him in some legal trouble. He escaped more severe repercussions for said trouble by agreeing to check himself into a psych ward. He was committed for seven months.

In 1954, four years after being released from the hospital, Ginsberg moved to San Francisco, where he immediately found his place among the set that would become the Beats.

As Jonah Raskin explains to NPR, “San Francisco was, in a way, a refuge for people from all over the country. In the ’40s there was a substantial community of anarchists, pacifists, experimental poets. In part because it was far away from the East Coast centers of power and you could do things that you couldn't do elsewhere, there was an invitation to experiment. Ginsberg became part of this intellectual and cultural scene right away.”

While Ginsberg arrived in the city with another corporate advertising job, he soon gave it up to focus his attention on writing the poem that would become Howl.

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,” the poem famously begins.

On Oct. 7, 1955, Ginsberg staged a culture-shaking reading of this new work for the first time. The crowd at Six Gallery was enthralled. Ferlinghetti was among the viewers that night—as was Kerouac. The City Lights maven soon worked out a deal with Ginsberg to publish Howl.

And with that decision, the ancient wheels of censorship began to turn. Ferlinghetti wasn’t naive. He knew Howl might cause a cultural dustup, so he decided to print the books in England, though the plan was always to send them straight to the U.S. He also showed the manuscript to the ACLU and lined up their support for whatever happened next.

Which was a good thing, because what happened next was like a scene out of a Charlie Chaplin movie.

One thousand copies of the were officially printed on Nov. 1, 1956. That printing escaped notice. But it was the second installment, released in early 1957, that drew the attention of San Francisco customs.

On March 25, 1957, Collector of Customs Chester McPhee had all 520 copies of the books seized as they entered U.S. soil. When that news came out, Ferlinghetti announced that he had managed to get 1,000 copies into the country at the same time and that every last one of those as well as the previous printing had quickly sold out.

Poor prude McPhee had probably anticipated pushback from the burgeoning beatniks of his city. But what he surely didn’t plan for was that he would also have to go against his counterparts on the other coast. Shortly after he issued his ban, the D.C. customs office overruled McPhee and gave Howl the green light.

But the customs officer did not give up his sanctimonious fight. McPhee may have lost the customs battle, but there were other authorities in San Francisco. He took his cause to the SFPD and convinced the men in blue to officially declare the book as “lewd.” They not only did that, but they took the initiative to stage their own sting operation at City Lights.

While this ping pong game over a volume of poetry continued, columnist Herb Caen was having a ball in the San Francisco Examiner.

In a column about the “characters around town” on May 14, 1957, he wrote about “The hungry intellectuals who hang around the City Lights bookshop in No. Beach—and, when the keeper isn’t looking, steal copies of Allen Ginsberg’s book of poetry, ‘Howl’.”

“When will those self-apptd. censors in the Police Dept. realize that by trying to ban Allen Ginsberg’s book of poetry, ‘Howl,’ they’re merely stirring up a big audience of curiosity-seekers who, left alone, would never have heard of it? That’s MY howl…,” he asked on June 7.

Three days later, he reported a sighting of Howl in the wild: “Poet Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl,’ banned here by the Intellectual Safeguards Div. of the Police Dept., is being peddled openly near the Cal campus in Berkeley. On guard, Berserkeley!”

In August of 1957, the trial of Ferlinghetti and his clerk who had actually sold the book to the undercover officer began. They were charged by the state of California for the crime of “willfully and lewdly print[ing], publish[ing] and sell[ing] obscene and indecent writings, papers and books, to wit: ‘Howl and Other Poems.’”

The question at hand was not whether or not Ginsberg’s poetry was obscene, but whether that element was part of what constituted a literary work of art or whether the poem was pure, valueless smut.

The sides were well divided. The prosecution was helmed by a publicly militant, anti-porn activist. Ferlinghetti was defended as promised by the ACLU as well as famous defender of the stars Jake Ehrlich. The judge was a Sunday school teacher and moral crusader.

The trial lasted nearly a month, with the typical starts and stops (the judge issued a continuance at one point so he could actually read Howl), and the stand was occupied by a a parade of literary scholars arguing for or against the merits of the poem. But in the end, free speech prevailed. The judge may not have liked Howl, but he did acknowledge Ginsberg’s literary intent and the work’s social value.

The sentiment was right in line with Ginsberg’s views on his art. As he later said, “Poetry is not an expression of the party line. It’s that time of night, lying in bed, thinking what you really think, making the private world public, that’s what the poet does.”

Ferlinghetti for his part was stunned when he was declared not guilty, but he sensed the decision “might foreshadow a sea change in American culture.” He was right. The trial launched Allen Ginsberg and the Beats into the national consciousness, a cultural movement that evolved into the Swinging Sixties and the rise of the hippies.

Writing in 2006, Ferlinghetti ended his reflection on that moment in his life with an urgent message that is still relevant today: “Fifty years later, Ginsberg’s indictment still rings in our ears, and his insurgent voice is needed more than ever, in this time of rampant nationalism and omnivorous corporate monoculture deadening the soul of the world.”

As for what happened after the trial, Ferlinghetti returned to selling books, namely the 5,000 copies of Howl that he quickly had printed after the trial to meet the exploding demand.