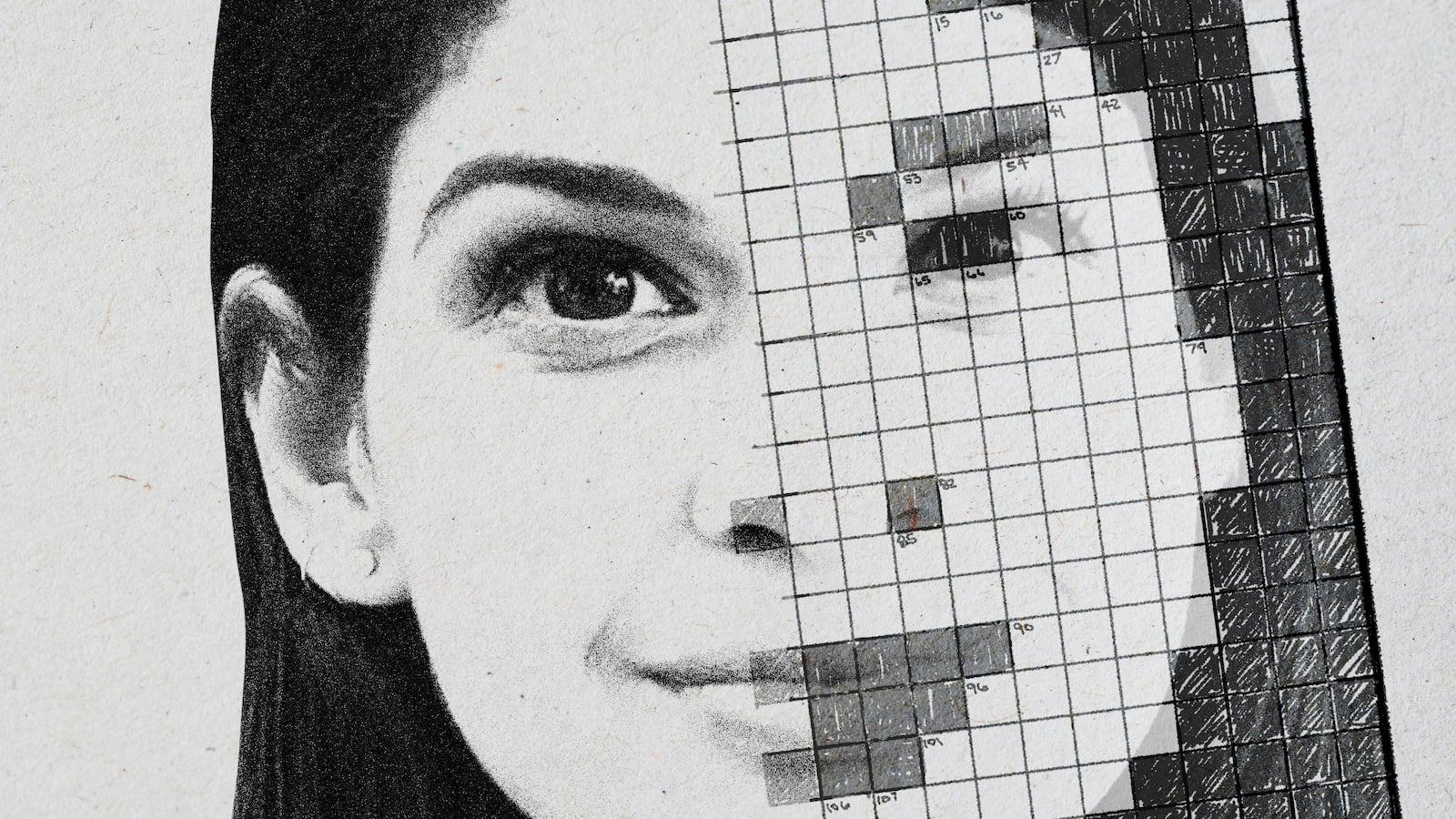

“I’m what they call a ‘cruciverbalist,’” Anna Shechtman says as she introduces herself. “It’s the term they use for crossword designers.” She pauses for a beat. “It always makes me think it should be a fancy word for a serial killer or something.”

That morbid, snarky, deadpan humor Shechtman hints at is why she’s become a star in the tiny community of cruciverbalists. Last spring, Shechtman was chosen to be part of a select group of cruciverbalists to help launch The New Yorker’s Monday crossword section, after publishing a crossword as a teenager in The New York Times.

Since then, Shechtman’s puzzles have become stars in their own right, dancing between sharp-tongued feminism, politics, and hat-tips to the cultural zeitgeist of the day. In doing so she’s welcoming a whole new class of crossword enthusiasts, particularly young women.

“Crosswords have this bad rap (justly earned in many quarters) for being excessively reliant on arcana and trivia,” Michael Sharp, an assistant professor of English at Binghamton University and considered a “master” of New York Times puzzles, told The Daily Beast. “Anna is very aware of this, and is trying actively in her puzzles to broaden the puzzle’s cultural reach, to be more inclusive in all kinds of ways, while also maintaining a sense of lightness, pleasure, and joy. It’s like she’s using her book smarts to welcome you, to hug you, rather than to test your worthiness.”

And that’s what makes Shechtman’s crosswords so delightfully, refreshingly feminist. Rather than stodgy trivia, her clues are eyebrow raising and boundary-pushing, dropping Beyoncé lyrics, challenging solvers to pencil in “outer edge of a smoky eye,” asking for “the cost of being a female consumer.”

Her clues speak to the fact that she’s an anomaly in the close-knit, tiny world of cruciverbalism. She’s a woman, and a young one at that. At 28, Shechtman has marked herself as a rebel, openly criticizing the inherent sexism and classism within the crosswording world. In her puzzles she advocates for the black and white squares to double as opportunities for puzzlers to reflect on their own actions and worldviews, however gray those may be. In doing so she is helping to make crosswords a vehicle for understanding our rapidly changing culture, while tapping into the resurgence of charming retro, analog hobbies.

Until she was 14 years old, Anna Shechtman had never done a crossword puzzle. Shechtman grew up in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood and had what she described as a fairly normal childhood.

But when the documentary Wordplay came out, she tagged along with her mother to SoHo to watch it. The film chronicles the infamous constructor of the New York Times crossword puzzle, Will Shortz, and crossword puzzle aficionados and cruciverbalists alike who savored—and sometimes grew frustrated by—Shortz’s clues.

“The movie is a little bit didactic—it actually instructs you on how to create a crossword puzzle,” she recalled. Something about the movie stuck with Shechtman, and without having ever penciled in a letter within the black and white boxes of a crossword puzzle before, she decided that she’d become a cruciverbalist.

Shechtman started off small. Her first crossword was for her high school newspaper. It was successful enough to become a regular feature. “I’d have puzzle themes about the lunch menu in the cafeteria and midterm exams,” she said with a laugh.

That continued to Swarthmore, where Shechtman became the crossword builder for the college newspaper, The Phoenix.

Unbeknownst to Shechtman, her college boyfriend submitted one of her crosswords to Shortz one day. To Shechtman’s surprise, Shortz accepted her crossword, launching the preternaturally talented cruciverbalist into the big leagues. No longer was crossword puzzle designing just an odd hobby; it was her job.

Even then, Shechtman’s puzzle challenged the traditional norms of a “normal” New York Times puzzle: Her clues included snide commentary (“modern education phenomenon” was GRADEINFLATION), snippy puns (“chokes after bean eating?” was GOESOUTONALIMA), and Twitterspeak (“noncommital suffix” was ISH).

Shechtman, after all, had had no formal training besides being a fanatic of a cult documentary; her experience prior to being Will Shortz’s assistant was limited to quirky, themed crosswords for her college peers who happened to grab the paper.

Almost immediately though she felt the male-female divide, something she hadn’t really known when her only exposure to cruciverbalism—“the crossworld”—was from Wordplay.

“In the movie, there’s actually a fair number of women featured because it’s mostly a movie about crossword solvers, and actually most crossword solvers tend to be women, but most constructors tend to be men, by a large margin,” she said.

That’s something that has arguably made crosswords similar: their overwhelmingly white, upper class, educated, cisgender male point of view have made them boring and uninspiring.

Shechtman was a 19-year-old sophomore when she burst onto the scene with a Wednesday puzzle in The New York Times and became a protege of Shortz. (She wasn’t the youngest ever published by the Times; that honor goes to then-14-year-old Ben Pall in 1995.)

“I was an outlier in the field,” Shechtman reflected. “It’s a male-dominated field, with a lot of men form computer sciences. And at the time [when she first started designing crosswords], I was a woman from New York who majored in humanities.”

Shechtman’s puzzles hit that cultural nerve and are often reflections of the culture she’s consuming. “I live in the internet,” she said. “The Spice Girls were the most important cultural phenomenon to me when I was in elementary school. I love Cardi B. Sex and the City was a huge thing for me in high school.”

These pop culture references have influenced her creative grids.

“I want the grid to feel like a variety of different people can recognize themselves,” she said. “Crossword puzzles can feel exclusionary. I want them to feel inclusionary. To me, I think of puzzles as a democratic institution.”

Shechtman said she immediately felt the brashness of her presence in the “crossworld” and how her worldview, age, and gender made her crosswords instantly foreign territory—ironic, given how accessibly littered with pop culture her crosswords are.

Shechtman thinks the gender imbalance exists between male designers and female solvers because most editors of major crossword puzzles are male, and women are often discouraged by “snarky” blogs and commentary online.

Elizabeth Gorski, a fellow female cruciverbalist, said the male/female divide of crosswording relates a lot to the fact that the design is often “autobiographical.” “We see a world through the constructor’s lens.The specific word choices and cluing angles are windows to a puzzlemaker’s soul, so to speak.”

She continued, “People’s perceptions are changed when puzzle markets actively recruit—and retain—experienced women constructors,” she said. “The buy-in from the top, the vote of confidence in their published work, and the belief that women constructors can do the job—these things change perception. Some markets do this very well”—including The New Yorker, which has Shechtman and another female cruciverbalist on rotation.

Today, Shechtman is a senior humanities editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books and working on her PhD in English & Film Studies at Yale. And every month or so, she publishes a puzzle with The New Yorker, where she’s garnered a legion of fans.

She’s also dedicated to teaching and mentoring other women about the art of cruciverbalism, hosting events at the Wing in New York “I want there to be more female crossword puzzle constructors, here are still not enough women entering the field,” she said.

“I got to share one of my grids built around feminist history [at the Wing],” Shechtman said, before adding, “it was considered (ugh) ‘too niche’ for the Times audience.”

Despite her work writing reviews, crosswords remain Shechtman’s first love. “I have to tell you that what was so gratifying and exciting about this [working with The New Yorker in designing crosswords] for me was letting my literary freak fly,” she said. “I can create a puzzle as a meta commentary about the literary and publishing industries.”

For Shechtman, that commentary ultimately can be educational for people who are shocked by the terms she drops in her work. “Why not make it a space for feminist expression?” she asked. “The personal and escapist is political. I think of the puzzle as a frame of reference. It’s not cheating to look up words, it’s learning. If you didn’t know what the ‘male gaze’ was but Googled it, I’m happy to have helped.”