Recent excavations in the ancient Kingdom of Judah, close to Jerusalem in Israel, has unearthed a number of anthropomorphic male figurine heads from the 10th century B.C. A bearded man with a square flat-topped head, protruding nose, holes for earrings, and somewhat bulging eyes. The similarity between the figurine heads suggests that they depict the same figure, but who is this oddly shaped character? In an article published this week, archaeologist and Hebrew University professor Yosef Garfinkel argues that they show the face of Yahweh, the God of Israel. If accurate the sensational claim would mean both that ancient Israelites made idols (despite the strict biblical commands not to) and that we now have an early portrait of God.

The results of Garfinkel’s research were published this week in Biblical Archaeology Review. Three figurine heads were recently excavated from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Tel Mozạ, sites located close to the modern city of Jerusalem. (Garfinkel also refers to two other figurines, that were almost certainly looted, but BAR does not publish unprovenanced artifacts). Garfinkel argues that the discovery of some horse-like figurines close by to the heads from Mozạ shows that, originally, this anthropomorphic figure was a rider on a horse. For Garfinkel it’s clear that the image depicts an ancient deity. The question is, which one?

There are several candidates up for the position. The Canaanite deity Baal (a rival of Yahweh’s in the Bible) is, as Nicholas Wyatt has written, repeatedly described as the “rider of the clouds” in ancient Ugaritic texts. Garfinkel argues, however, that the figure isn’t Baal but, rather, Yahweh. The same language of riding the clouds, he writes, appears in the Psalms, Deuteronomy, 2 Kings, Isaiah, and Habbukuk. Psalm 68:4 reads, “Sing to God, sing praises to his name; lift up a song to him who rides upon the clouds.”

Which is it? Is the figurine Yahweh, the protector of Israel or Baal, the Canaanite storm God who enjoyed infant sacrifice?

“The Canaanites,” writes Garfinkel “did not depict a male god on a horse. Only in Iron Age texts and iconography does the horse became a divine companion animal. So, the iconographic elements of the figurines correspond with descriptions of Yahweh in the biblical tradition.”

Tenth and ninth century B.C. pilgrims, he argues, would have journeyed to cultic centers in order to see the face of Yahweh. Just as other ancient Near Eastern pilgrims were shown the face of God, so too devotees of Yahweh were able to see the face of the idol. This encounter between the pilgrim and the face of God, he writes, was an important religious experience and “metaphysical moment” in which heaven and earth are brought together.

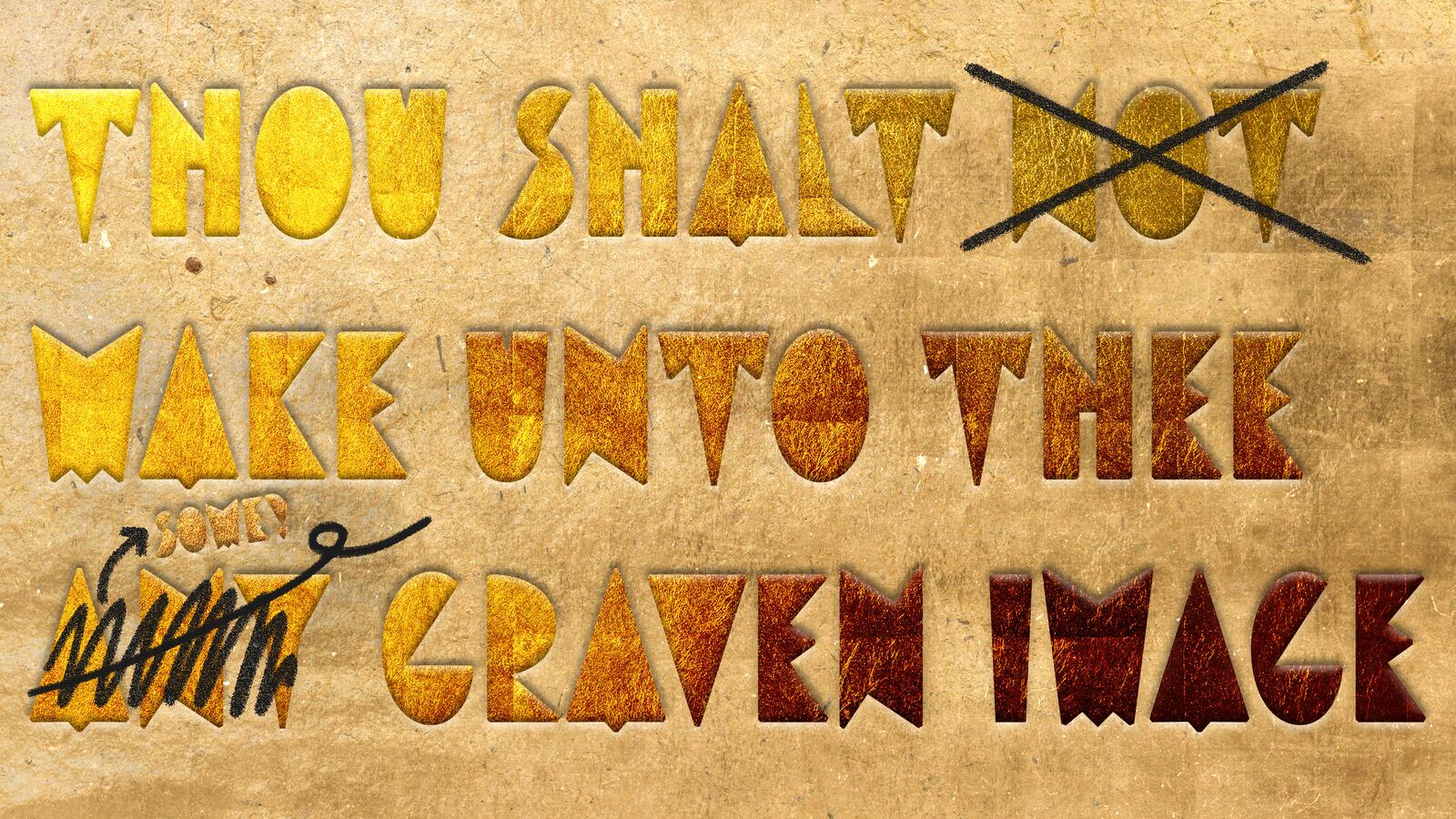

One straightforward objection to Garfinkel’s hypothesis is that this is just the kind of thing that the Bible tells ancient Israelites not to do. Idols are expressly prohibited in a number of texts including the Ten Commandments. Maybe the references to seeing the face of God in the Hebrew Bible are strictly metaphorical? Drawing on earlier scholarship, Garfinkel argues that the ban on cultic images of Yahweh was not operative in the 10th century, when the figurines were in use, but was only introduced during the eight century B.C.

It’s a bold and eye-opening claim, but there are many who disagree. In an article published earlier this year, University of Tel Aviv scholars Shua Kisilevitz and Oded Lipschits, the archaeologists who oversee excavations at Tel Mozạ, argued something quite different about the temple where two of the figurines were found. While Kisilevits and Lipschits agree that the figurines are cultic objects, they do not believe that they are images of Yahweh. Noting parallels to the example from Khirbet Qeiyafa and other examples from the region, they describe them as “human figures” that were used in ritual practices in the temple at Tel Mozạ. They persuasively argue that the previously unknown temple at Mozạ was dedicated to the worship of a local Canaanite fertility deity. The cultic center in Jerusalem allowed the Canaanite temple to remain active because it produced a great deal of revenue. In sum, the figurines can’t be images of Yahweh, because this was never a temple dedicated to Yahweh.

When it comes to interpreting the archaeology of ancient Israel, tensions run high. Lipschits regularly clashes with Garfinkel on matters of archaeological interpretation; in particular, Garfinkel’s pattern of linking all of his discoveries from the 10th century to biblical and national hero King David. In a recent interview on King David for the New Yorker, Lipschits said “Yossi Garfinkel is a prehistorian who hadn’t dealt with this period before, and he came into it with no real understanding.”

This is more than just an academic disagreement turned public spat, however; the political and financial stakes are high. There are many, both Jewish and Christian, who are invested in the Bible’s narrative of conquest for political or religious reasons and sponsor excavations in the region. For these putative investors King David is more appealing than ancient Canaanite society. William Schniedewind, a professor at UCLA, intimated that these motivations may be at work when he told the New Yorker that Garfinkel’s excavations “have been seminal, but his interpretations sometimes are a little bit... Well, I mean, you need money, right?” The first season of Garfinkel’s excavations at Qeiyafa, for example, were sponsored by Foundation Stone, an organization that uses history to support a particular notion of Jewish identity.

Prof. Robert Cargill, the editor of BAR and an archaeology professor at the University of Iowa, told The Daily Beast that the magazine’s mandate “is to report the claims made by professional archaeologists at licensed excavations in Israel… while [Garfinkel’s claims are] certainly a sensational interpretation and minority opinion, we felt obligated to publish the claim made by this tenured Hebrew University of Jerusalem professor of archaeology.”

The jury is out on whether or not these figurines actually depict Yahweh, the God of Israel, but if they do we have learned something unexpected about the appearance of God. In addition to riding a horse, sporting a beard, and wearing his hair in a longish COVID-era style, he also has pierced ears.