This summer a new documentary TV series premiered on the Discovery Channel. Hunting Atlantis follows a pair of experts “on a quest to solve the greatest archaeological mystery of all time—the rediscovery of Atlantis.” There’s just one problem: there’s not an ancient historian or archeologist working in the field today who believes Atlantis was a real historical city.

Academics and documentary filmmakers often find themselves at odds, but as criticism of the show spilled over onto social media things turned ugly. A well-respected archaeologist was verbally abused by a flood of true believers who were committed not just to Atlantis, but also to white supremacy and eugenics.

Hunting Atlantis is co-hosted by Stel Pavlou and volcanologist Jess Phoenix. Phoenix is an expert in natural disasters (specifically volcanic eruptions), who has spent a great deal of time in the field as a geologist. In 2018 she even ran for Congress. Pavlou is a successful TV host, producer, screenwriter, and bestselling author: one of his films is a cult classic and his children’s books have won awards. The basis for their show is Pavlou’s argument that the date of Atlantis’s destruction should be placed at the beginning of the fifth millennium BCE.

That the show has something of a sensational bent is to be expected; making archeology TV friendly often involves inflating or sensationalizing what can otherwise be quite dry material. There are also certain ancient artifacts and locations—like the Holy Grail or Noah’s Ark—that hold the attention of viewers and will always be evergreens for documentary history-telling.

As bioarchaeologist Stephanie Halmhofer has discussed in an insightful blog post, everybody loves Atlantis, “thanks to things like Disney’s Atlantis: The Lost Empire, DC’s Aquaman, and the popular television show Stargate: Atlantis.” People are broadly familiar with it as a cherished part of their childhood imagination.

The difference between the Ark and Atlantis is that while people acknowledge that there was a cup that Jesus drunk out of or that the Ark of the Covenant existed, I don’t know any archeologists who think Atlantis was a real place. Searching for it, for most archeologists, is only slightly more reasonable than hunting for Narnia. “Greatest archeological mystery” it is not.

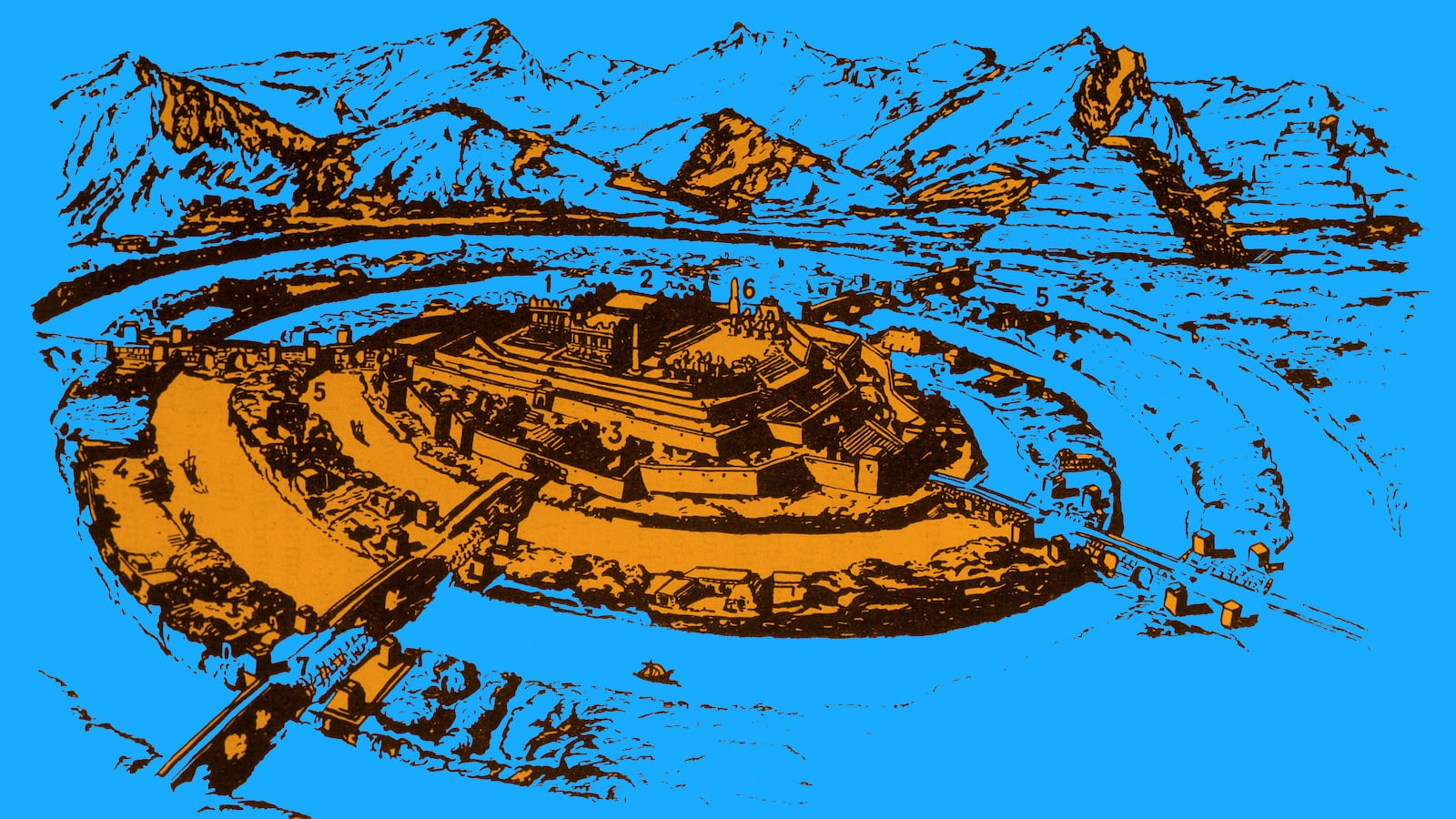

Our sources for Atlantis are the philosophical dialogues of Plato (specifically the Republic, Timaeus, and Critias) in which characters in the fictional dialog have a hypothetical conversation about the ideal society. Atlantis, in Plato’s imagination, was a technologically advanced and harmonious society that gradually descended into corruption, disorder, and greedy warmongering. It was ultimately destroyed by a series of earthquakes that led to the city disappearing into the ocean.

It was the presentation of Atlantis as an actual place that drew concern from archaeologists when the show was first announced in May 2021. With so much rigorous archaeological research going undiscussed and underfunded, there was a palpable sense of frustration that a popular channel would air another show on what experts call pseudoarcheology.

To his credit, when challenged on social media, Pavlou offered to share what he described as the “academic” paper on which the show was based. Having been volunteered by a colleague, Dr. Flint Dibble, a Mediterranean archeologist and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at Cardiff University, rose to the challenge.

Dibble was unimpressed: “I read the paper carefully, refreshed my own research on Plato and the archaeology of Athens in the 5th millennium BCE and wrote a Twitter thread. This thread debunked the paper and exposed its logical faults in some places where scholarly research was cited, explored examples where conclusions were drawn from uncited statements.”

The scholarly consensus, he told me, is very clear: Atlantis was not a real place.

After watching the show, Dibble said, he remained unpersuaded. He was concerned by the way that the credible research of legitimate archaeologists was being used to prop unfounded claims about Atlantis. If you watch carefully, he explained, you’ll notice that “scholars never mention the name ‘Atlantis’ nor ‘Plato’ on air. At no times on air do the two co-hosts …ask the scholars any questions about Atlantis or bring it up in front of them.”

When I corresponded with Pavlou he was frustrated with the response from academics on social media. “At no point have I ever claimed Atlantis is real,” he said, “I find it hard to believe [Plato] invented the whole story… None of [the research I have done] proves that Atlantis is real but [it] does suggest there may have been a real myth buried somewhere behind Plato’s writing.” Pavlou told me that he is “agnostic” about the existence of Atlantis: “Atlantis as Plato wrote it certainly doesn’t exist” but there may have been a myth tied to the memory of earlier geological events.

There are many reasons that scholars would dispute this more nuanced claim, but this is a different kind of argument. But even so this is not the impression one gets from watching the show. The series ends with Pavlou saying that, “It feels like Atlantis could be right beneath our feet.” A feeling is not a statement of fact, but this and many other elements in the show imply a belief in the historical Atlantis.

When I asked Pavlou why an Atlantis-agnostic would make a show called Hunting Atlantis he claimed that he had originally pitched the series as a myth busting style show. He wasn’t even originally supposed to host it, he added. Over time, and with input from producers and executives, the series morphed into something else: a show grounded in his theories of a preexisting earlier myth. As someone who has made documentaries myself, I have to wonder: what parts of the show stem from the host, which are the input of the production team, and what is just slick marketing?

Dibble told me that he asked the hosts and producers for a comment about misrepresenting the research of the academics interviewed on the show. This is when things started to get heated, Pavlou’s wife made some ad hominem attacks on Dibble that questioned his credentials and dragged his family into the fray (Dibble’s father was a famous archeologist, but in a different period and field).

Dibble, in turn, contextualized his objections by exploring the problematic ways that Atlantis has been utilized throughout history. By the next day, Dibble said, both he and Pavlou were engaged in a full-on Twitterstorm. He woke up to “hundreds of colleagues and supporters” defending him to Pavlou and similar numbers of Atlantis-believers trying to dispute his claims and insulting him.

“At one point,” he said, “Robert Sepehr, a pseudoarchaeologist who has a YouTube channel called ‘Atlantean Gardens’ and praises Nazi research, began targeting colleagues and friends who were tweeting about the situation.” From archeology to white supremacists overnight, the bizarre situation raises the question: how did we get here?

For almost two thousand years after Plato’s death everyone read the story about Atlantis for what it was: a fictional account about an ideal city that lost its way and was being use by Plato as a foil for his hometown of Athens.

Interest in Atlantis as a real place first emerged, writes Halmhofer, in the 1500s when early European explorers wondered if the indigenous people of Central America were the descendants of the Atlanteans. Interest in this theory continued to build over several centuries until, in 1882, Ignatius Donnelly published his highly influential book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World and inaugurated a new era of study. In it, Donnelly claimed that Atlantis was the origin point for human civilization. Others took up this cause and argued that the Atlanteans were the ancestors of a particular group of people: the “Aryan race.” This, as I imagine you have already guessed, is where things take a dark turn.

As Halmhofer writes on her blog and Dibble articulates in one of his Twitter threads, the “history” of Atlantis has, since the nineteenth century, been interwoven with the study of evolution and eugenics. Plato ends the Critias with a discussion of how the divine nature of the Atlantides was corrupted when it was mixed with the inferior nature of mere human beings.

The discussion lends itself well to 19th and 20th century eugenicist theories of the races. The Nazi Institute of Atlantis founded by Himmler aimed to find evidence for the theory that the Aryan race was descended from the biologically divine Atlantides.

To be inescapably clear, racism and eugenics are not at work in Hunting Atlantis. On this Pavlou and Dibble are in agreement. Pavlou told me “There is nothing about the show, my paper, or the way I live my life that has any connection whatsoever.” Dibble agreed “[Pavlou’s] family fought Nazis in WWII…he seems like he would be someone fun to have a beer with, if it wasn't for this show and the Twitter eruption from it.” Some worry, though, that white supremacists might use this show to support their dangerous claims. Indeed, some already are.

While many people love reading archeological fan fiction in their youth and some become archaeologists because of it, pseudoarcheology is not always harmless. We find ourselves in a difficult position. Where are the boundaries between pseudoarcheology, slick soundbites, and minority opinions? Do good production values always mean bad or exaggerated archeology? And, is every writer, TV host, or academic responsible for the potential misreading or misuse of our arguments?

None of us begrudge children who love comics about Atlantis or expect to receive a letter from Hogwarts, but does the blurring of the line between minority opinion and scientific facts harm cultural and scientific literacy in wider society? Can we afford confusion in a society already plagued by a lack of trust in expertise and information accuracy?

Academic concerns about how ancient history can be used by white supremacists are far from unique; the poster child for this issue is the wildly successful show Ancient Aliens. Here the problem is even more acute because crediting aliens for human ingenuity involves erasing the contributions and work of historically excluded groups. In this series, a team of commentators–most famously the meme-able Georgio Tsoukalos—analyze ancient artifacts and suggest that they were built by or refer to extraterrestrials.

For several years Dr. David Anderson at Radford University has criticized the show and called for a retraction of some of its claims. Anderson told me that many of the claims made in the show are based on troubling older work. As an example, he mentioned the sarcophagus lid of the Maya ruler of Pacal. In 1968 international best-selling author, theme-park founder, and convicted white collar criminal Erich von Däniken—whose book Chariots of the Gods pioneered the ‘Ancient Aliens’ theories—claimed that the image was an astronaut blasting off in a spaceship.

A recent tweet by Tsoukalos rehearses this interpretation. “The basic issue”, said Anderson, “is [that] these claims don't even begin to ask where or when Pacal's sarcophagus was found and what it might have meant to the Maya, they simply squint at a confusing image from a foreign culture and say it kind of looks like a rocket ship.

When we compare this image to other pieces of Maya art we find that it is full of symbols that are widely known and repeated.” There’s no mystery here: the lid “depicts a Maya ruler falling from this world to the underworld at the moment of his death.” The artifacts are taken out of their original context, people are asked “what does this look like to you?” and an alien genealogy is offered with no regard for ancient interpretations or contexts.

Then there’s the “helicopter” found in the temple of the Egyptian Pharoah Seti I at Abydos. Ancient Aliens suggests that a strange looking hieroglyph is a helicopter or flying saucer but traditional archeology identifies it as a re-carved inscription in which one name had replaced another. It might look strange but this, said Anderson, is just because the paint has been chipped away. The roots of many of von Däniken’s theories about Ancient Aliens are actually pop culture. The theory that aliens built the pyramids, for example, first shows up in the 1898 science fiction novel, Edison’s Conquest of Mars. In a forthcoming article, Anderson shows that von Däniken was pipped to the post by science fiction writers who had already hypothesized that ancient people would have confused aliens with gods.

To say that the theories that underpin Ancient Aliens have been rejected is to understate the case. In the foreword to a book debunking von Däniken’s claims Carl Sagan wrote: “That writing as careless as von Däniken's, whose principal thesis is that our ancestors were dummies, should be so popular is a sober commentary on the credulousness and despair of our times. I also hope for the continuing popularity of books like Chariots of the Gods? in high school and college logic courses, as object lessons in sloppy thinking.”

The troubling part of this kind of pop entertainment isn’t so much that it’s wrong (though that is incredibly frustrating to academics), but rather that it erodes the accomplishments and ingenuity of ancient peoples. As University of Iowa historian Sarah Bond has written, it is not a coincidence that these peoples are almost universally non-white and non-European (the lone European outlier, of course, is Stonehenge). The racist assumption that indigenous peoples weren’t intelligent or “evolved” enough to build the Native American earthen mounds in the eastern half of the United States or the Great Zimbabwe in Africa fed early twentieth century archeology and public policy. In fact, said Anderson, “when President Andrew Jackson called for the removal of Native Americans to Oklahoma, a call that led to the ‘Trail of Tears,’ he did so [by] invoking the lost white race of Mound Builders.” Bad archeology has violent real-world consequences.

This is not to say, as professor and Ancient Aliens voice-of-reason Robert Cargill, has pointed out that everyone who believes in ancient alien theory is racist. The problem is structural and systemic, but in some cases, the racism is shockingly straightforward. Museum curator Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews has gathered choice quotes from various archeologists including a von Däniken ‘question’ that went: “was the black race a failure and did the extraterrestrials change the genetic code by gene surgery and then programme a white or yellow race? [sic]”

As modern archeologists have debunked the racist assumptions that everything of value was built by white people, the conspiracy theories have just shifted target. The aliens-theorists are the heirs to this lineage. Anderson told me, “Ancient Alien authors started picking up the same examples of temples and monuments that European Colonialists imagined being built by lost white races but instead imagined that that they were built by extraterrestrials.”

The same assumptions of indigenous incompetence are at the heart of alien mythologies, yet with 196 episodes and sixteen seasons under its belt the Ancient Aliens juggernaut continues apace.

Looking at Hunting Atlantis, perhaps the lingering question here is, what and who is excluded by the Atlantis myth? Why do we search for this fictional utopia? Is our collective fascination with and search for Atlantis a form of escapism? Bond, who has tweeted one example of cultural erasure involving Atlantis, said to me, “People would rather focus on it than the mess we live in now. But ignoring science is what got us into this mess in the first place.”

Does the search for a perfect city prevent us from fixing our own social problems in the present? If it does then perhaps part of the blames lies with us, the viewing public? Only time will tell but, in the meantime, the mythic status of Atlantis has been settled by unlikely authority: IMDB.com categorizes the show as fantasy.