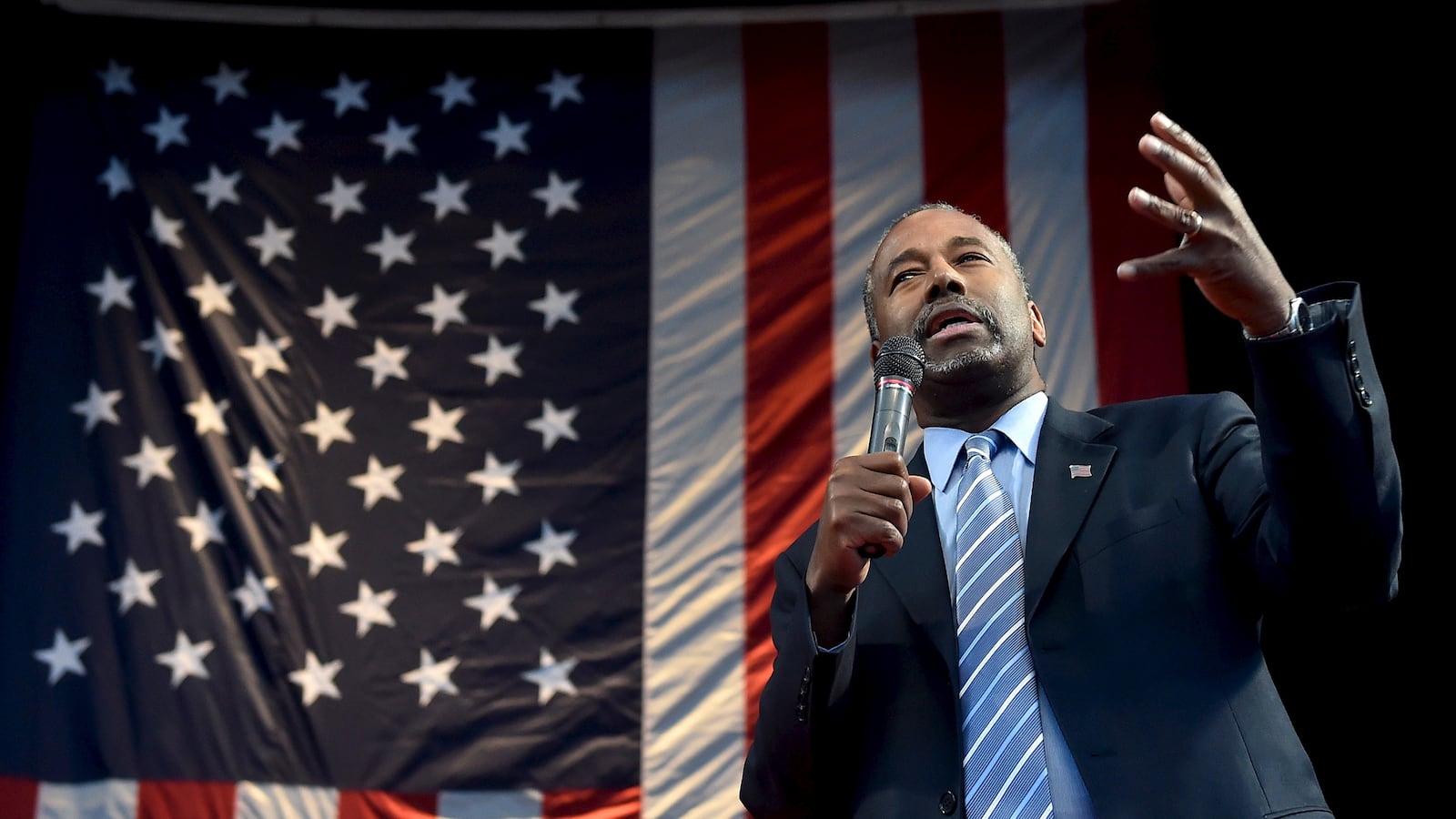

Ben Carson doesn’t have a lot of time to go to Saturday services at the Spencerville Seventh-day Adventist Church anymore but his fellow Seventh-day Adventists are fine with the glare of the presidential race being far away.

Carson has made his faith a central part of his campaign for president and credits it for his extraordinary accomplishments over the course of his life.

However, there is trepidation among many of the church’s thought leaders about their association with a candidate for political office. And some simply view his controversy-prone bid for the White House as a lose-lose for the church’s public image.

There are nearly 1.2 million Seventh-day Adventists in the United States. Followers abide by many elements of Evangelical Protestant doctrine but emphasize the importance of the Saturday Sabbath, promote religious liberty, focus on diet and health, and want to preserve conservative values like same-sex marriage. They are also firm believers in the eventual Second Coming of Jesus Christ and that those who don’t accept him linger in eternal sleep rather than go to hell. Some of the more controversial elements of the faith stem from the writings of co-founder and 19th-century prophet Ellen White, who saw in a vision that the U.S. government would unite with apostate Protestants and the Roman Catholic Church to suppress the Saturday Sabbath and imprison those who practiced it.

Spencerville, where Carson belongs, is a mainstream Adventist church by most standards, according to theologian Jonathan K. Paulien, which means not all of White’s writings are taken as gospel.

Located in Silver Spring, Maryland, about 45 minutes by car from the Capitol, the church’s aesthetic is an amalgamation of old and new. The ceiling has sloping panelled wood meeting at a triangular point above the pews, drawing attention to the central focus of the area of worship: a massive organ bathed in the light of a towering stained-glass window behind it.

The window depicts a passage in the book of Revelation, representing a central tenet of the Adventist faith. Three angels carry messages to be delivered to the world, including “a book containing the everlasting gospel,” the church’s website reads, a call to bring men and women out of apostasy and a reminder for people to focus on the commandments of God rather than seeking righteousness simply through human effort alone.

“Welcome to worship at Spencerville Church,” this past Saturday’s service began. “We’re happy to see you all.”

A choir decked in purple robes sang the “Hymn of Praise No. 300,” according to the program, welcoming newly appointed Pastor Chad Stuart to the pulpit with ringing repetitions of “Hallelujah.”

Stuart, whose blond shock of hair is reminiscent of 98 Degrees-era boy bands, has been with the church for a year.

His first words on Saturday, facing pews which slanted diagonally inwards toward the center, were focused on the horrific terrorist attacks in Paris on Friday.

“Be consistent in prayer,” Stuart asked the congregation on behalf of those suffering. The events, according to his faith, add to a mounting feeling that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ is nearing. Without positing a guess as to when this ultimate salvation for Adventists would be, Stuart said in an interview with The Daily Beast that the world’s ongoing tumult makes it all the more clear that those who accept Jesus Christ as their lord and savior will find an ultimate place with him in heaven at some point in the future.

“As things grow more and more troublesome, there’s a greater and greater—we believe—indicator of the nearness of the Lord’s return,” Stuart said, careful to not distinguish the attacks in Paris as the sole sign of the imminent salvation. “We are attentive to the fact that no one knows the day or the hour, but it seems that the world is in greater chaos as we go along. Unsolvable chaos in some ways.”

This is one of the central Adventist tenets with which Carson agrees, drawing skepticism from mainstream media.

He once told Sharyl Attkisson you could guess that we are getting closer to “the biblical End Times.” In an apparent effort to maintain his grip on evangelicals, Donald Trump attempted to make it an issue, telling a crowd in Florida, “I’m Presbyterian. Boy, that’s down the middle of the road, folks, in all fairness. I mean, Seventh-day Adventist, I don’t know about. I just don’t know about."

And while the approach of the end of days may seem like an odd idea to some, especially when tethered to calamitous world events like the Paris terrorist attack, 41 percent of Americans said they believe that Christ will return by 2050, according to a 2010 Pew Research Center poll. Carson has an 87 percent approval rating with white born-again evangelicals.

The conundrum Ben Carson presents to Seventh-day Adventists is not about how he expresses his faith. But that inherently, they are cautious about mixing their politics with religion.

“I think there’s a feeling among some of the more professional Adventists that this isn’t a win-win, it’s a lose-lose for the church,” David Trim, the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s archivist, told The Daily Beast.

“I’ll be honest with you, I’m a little more centrist in my political views than him and I find some of the things he says really rather troubling or just doesn’t make any sense. The feeling is, ‘Will we be tarred with a brush because of what he says?’” Trim said. “Or even if he turns out to be—even if he were a more unifying figure than he is—would the position that he has to adopt to be elected be such that he’d have to compromise his principles, and then the church wouldn’t be happy with that either. It’s kind of like, can this really end well for us?”

Trim, who is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and has written extensively on the history of his faith, said the question for some is whether an Adventist should be getting involved in politics at all.

In May, the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s North American Division released a statement saying there would be no formal endorsement of Carson’s candidacy.

“The Adventist Church has a longstanding position of not supporting or opposing any candidate for elected office,” the statement read. “This position is based both on our historical position of separation of church and state and the applicable federal law relating to the church’s tax-exempt status.”

This message rang loud and clear even at Spencerville. Daniel Weber, the director of communication for the Seventh-day Adventist Church in North America, would not permit interviews with church attendees about their knowledge of Carson. Pastor Stuart expressed a similar lack of desire to discuss politics and Carson’s campaign did not provide a comment for this article.

“There’s the perception that things go badly for religion whenever religion and the state unite,” Jon Paulien, dean of the School of Religion at Loma Linda University, told The Daily Beast. He is a prominent Seventh-day Adventist theologian and author who runs a site called “The Battle for Armageddon.”

Paulien thinks Carson’s rise offers a chance to explain Seventh-day Adventism to more people.

“Adventists I’m aware of are in two camps. The one camp, probably the larger camp, is delighted that a Seventh-day Adventist is taking on such a prominent role,” Paulien said. “It gives us a chance to state our case to a wider public that maybe didn’t know us before. I think a lot of Adventists are very happy about that.”

Others, he said, who may be more liberal, “are horrified by some of the things he’s said or at least been reported to have said.”

Paulien also said that the skepticism Seventh-day Adventists have in regards to the political process has made some wary of “Ben Carson getting into bed with evangelical politicians.”

“We have a history of being advocates for religious liberty because we suffered from it in our early days,” Trim said. “Adventists were imprisoned for keeping Saturday a Sabbath and for working on Sunday. Adventists have always been a bit more skeptical about the American myth of religious tolerance than many American Protestants would be.”

Carson doesn’t have to worry about being imprisoned for working on a Sunday, but his schedule may be different than others in a potential administration.

Even now on a given Saturday, Carson is far from the confines of Spencerville, where attendees are given envelopes for tithe offerings during service. But he carries the faith with him everywhere, even proposing tithes as a model for federal tax plans. And his story of devout redemption, a transition from angry teen to willing subject of God, was told in a somewhat different iteration in the sermon this past Saturday.

Pastor Stuart spent almost 30 minutes humorously delivering a series of anecdotes that were meant to be allegories about letting Jesus Christ take over one’s life. In one, he says he spent an entire day of his youth trying to figure out why he smelled bad, only to discover that he had put on a musty undershirt before leaving the house in the morning. This silly tale turned into a rationale for forsaking what is bad in one’s life by accepting the Lord.

“If we allow these things to linger,” Stuart said to the congregation, “even what is good will eventually become corrupt.”

And if people don’t give themselves up for Jesus, Stuart says, they are destined to spend an eternity in the grave. He explained that modern Adventists don’t believe in eternal hell but rather an eternal kind of sleep.

“At the Second Coming of Christ, the trumpet of God and the voice of the archangel looks down and the dead in Christ will rise first,” Stuart told me. “At that point people will go up to heaven. We don’t believe in a god that tortures people for all eternity.”

This is a departure from the work of White, who referenced hell in many of her writings.

According to Trim, many modern Adventists really only adhere to White’s writing about the benefits of drinking water and emphasis on healthy practices. And Carson’s campaign has denied in the past that he believes that her foretold prophecy will take place.

In recent interviews, Carson has cautiously embraced his faith, so as to keep appealing to his base, while dispelling the more outlandish preconceived notions about it.

"I think there’s a wide variety of interpretations of that,” Carson told the AP in response to a question about White’s particular End Times scenario. “There’s a lot of persecution of Christians going on already in other parts of world. And some people assume that’s going to happen every place. I’m not sure that’s an appropriate assumption.”

What is an appropriate assumption is that Carson and his church’s emphasis on giving oneself to Jesus to guarantee a spot in heaven when End Times near, is central to the Seventh-day Adventist faith and the candidate’s own biography.

“I don’t have the power to overcome the sinful state within me,” Pastor Stuart told me. “I have to rely upon the grace and the work of the Lord.”

“Trust in the Lord with all your heart ... and he will direct your path,” Carson said, quoting the Bible’s Book of Proverbs at a recent address at Liberty University.

“I have clung to that through all kind of adversity in my life. I cling to it now because so many in the media want to bring me down because I represent something they can’t stand.”

Even as Carson ventures far from Spencerville Church and its congregation of suit-wearing adults and Bible iPhone app-toting kids, the doctrine of the faith doesn’t venture far from him.

And as Seventh-day Adventists observe with mixed emotions, for better or worse, his faith is paying off.