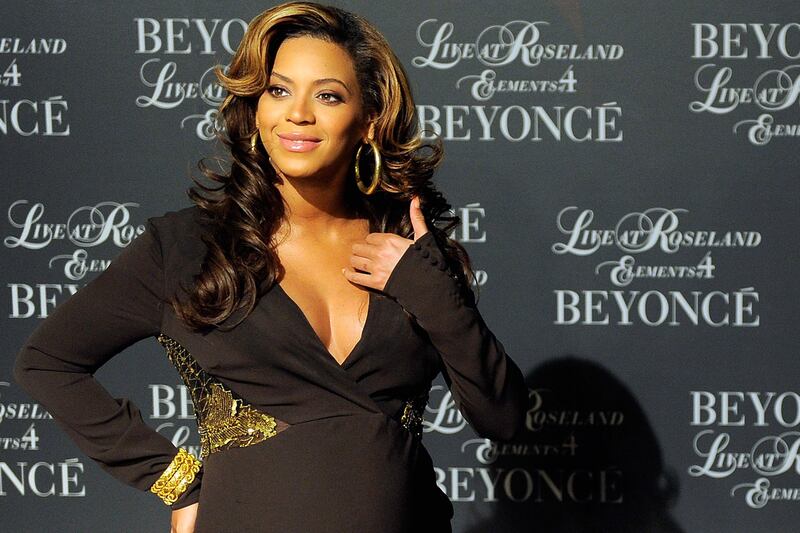

The flawless face of Beyoncé Knowles is more than a frequent guest on our television sets, courtesy of her electrifying commercials for L’Oréal.

Whether the singing sensation is hawking a new hair color, lipstick or foundation formulation seems to barely matter; the audience is simply captivated by her presence.

But lately, even in the midst of Blue Ivy mania, Beyoncé’s choice of ad material has received its fair share of criticism and complaints. Oddly enough, the dissatisfaction isn’t being directed toward the product or even the L’Oréal brand itself. It’s all about the skin. The skin Beyoncé’s in.

While appearing in the new ads for the L’Oreal foundation True Match, the 30-year-old mother of Blue Ivy cites her mixed racial background of “African American, French, and Native American.” She notes that her skin’s combined mixture is the reason the patented technology behind the foundation works so well.

The commercial immediately set off a firestorm of controversy with one very simple question: Why isn’t being “just black” good enough?

“When I first saw the commercial, I didn’t know what to make of it,’’ says Fred Mwangaguhunga, editor of Media Take Out, one of the largest African American entertainment websites in the country. “You know you’re used to hearing black people say they’re mixed with something to appear different from everyone else. But we’re all mixed with something—and we’re still just black.’’

L’Oréal also received stinging criticism in 2008 for displaying ads with Beyoncé that seemed to digitally lighten her complexion while editing her nose to appear slimmer. L’Oréal denied the accusations.

Fueling fire to the debate is Jennifer Lopez’s ad for the very same foundation in which she describes herself as “100 percent Puerto Rican.”

“Jennifer had her own backlash years ago in Hollywood when she tried to portray ‘colorless’ in films,’’ says 21-year-old Hosea Reyes, a film and race relations student at UCLA. “I think she learned from that how careful you have to be when you identify yourself in a world that still defines everyone by race. Being a celebrity doesn’t make you immune to that.’’

Skin color and its importance around the world—and particularly in the African-American community—has been a hot-button issue for generations. The debate over skin color and its painful origins dates back to the days of slavery, when lighter skin often equaled a better overall quality of life. With more pronounced European features, bearers of a lighter complexion were also considered more attractive than their darker-skinned peers. Possessing this trait was believed to open the cracked doors of opportunity ever wider.

Attitudes haven’t veered very far from that notion, says noted character actor (Predator, American Gigolo) and film producer Bill Duke. The veteran Hollywood actor recently produced and directed the haunting documentary Dark Girls, which examines the lives of African American women whose dark skin tones often have no “true match” when they approach the cosmetics counters.

“In the 1960s they did a test on young black girls by showing them dolls of all colors,’’ says Duke. “Each time they were shown the dolls and asked which wasn’t pretty or smart, they pointed to the black doll—the one that looked most like them. They did that same test recently and the results were the same. What does that tell you?’’

The documentary features heartbreaking personal accounts by women dismissed as unattractive and unworthy based on mainstream ideals of beauty. One young woman painfully describes her own mother’s suggestion that she’d be even prettier with a lighter skin tone. Another discusses being bathed by her grandmother as a child with lye soap in an effort to lighten her complexion.

Duke stresses the African American community’s continued confusion and denial of a bias toward darker-skinned African Americans by other African Americans. He suggests that the community’s message will only foster feelings of low self-esteem and rejection among future generations.

“I’m a dark-skin man, so I know the mean and ugly things said to me by other black people,’’ says Duke. “Then I had to watch my sister and now my young nieces face the same thing. We shouldn’t be here, but we are. We have to practice a self love with being black, no matter what that black may look like.’’

Some say it is in fact that intense sensitivity to skin color and race that’s unfairly made Beyoncé a controversial figure when matters of beauty and its meaning arise. In an earlier interview with Newsweek magazine, the singer admitted feeling harshly judged by others because of the lightness of her skin.

“I think people look at me and jump to conclusions without getting to know me,’’ said Beyoncé. “I think they think I feel I’m better because of my skin, and I don’t. The unfairness goes both ways.’’

Damone Roberts, a member of Beyoncé's “glam squad,’’ says criticism of the superstar appears to have no bounds.

“A lot of people have been trying to find something to hate about Beyoncé since the beginning,’’ says Roberts. “I know her and I know she’s not trying to be anyone other than who she really is.”

The discussion is the right step into understanding the pain behind the bias of skin color, but Bill Duke doesn’t expect an end to the debate anytime soon. That’s one reason he’s taking Dark Girls from city to city for viewing and discussion.

“Seventy-five percent of people really get it when they see it,’’ says Duke. “The other 25 percent complain about me airing ‘our dirty laundry.' ’’

To address Beyoncé’s point of view on the issue, Duke is currently working on The Yellow Brick Road, a documentary examining stigma and issues faced by women with lighter skin tones.