As the call to remove the Confederate flag from its official position in states across the South gathers momentum, the question that remains is, How far should this process go?

New York Times columnist David Brooks has responded to that question by observing that we now have a Robert E. Lee problem.

Brooks is, unfortunately, only half right. Lee, who led the South’s armies in the Civil War, should be distinguished from a racial extremist like Confederate general and slave trader Nathan Bedford Forrest, who became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. But as the recent exchange between CNN’s Legal View host Ashley Banfield and CNN news anchor Don Lemon shows, Lee is not our hardest problem when it comes to dealing with the South’s slave legacy.

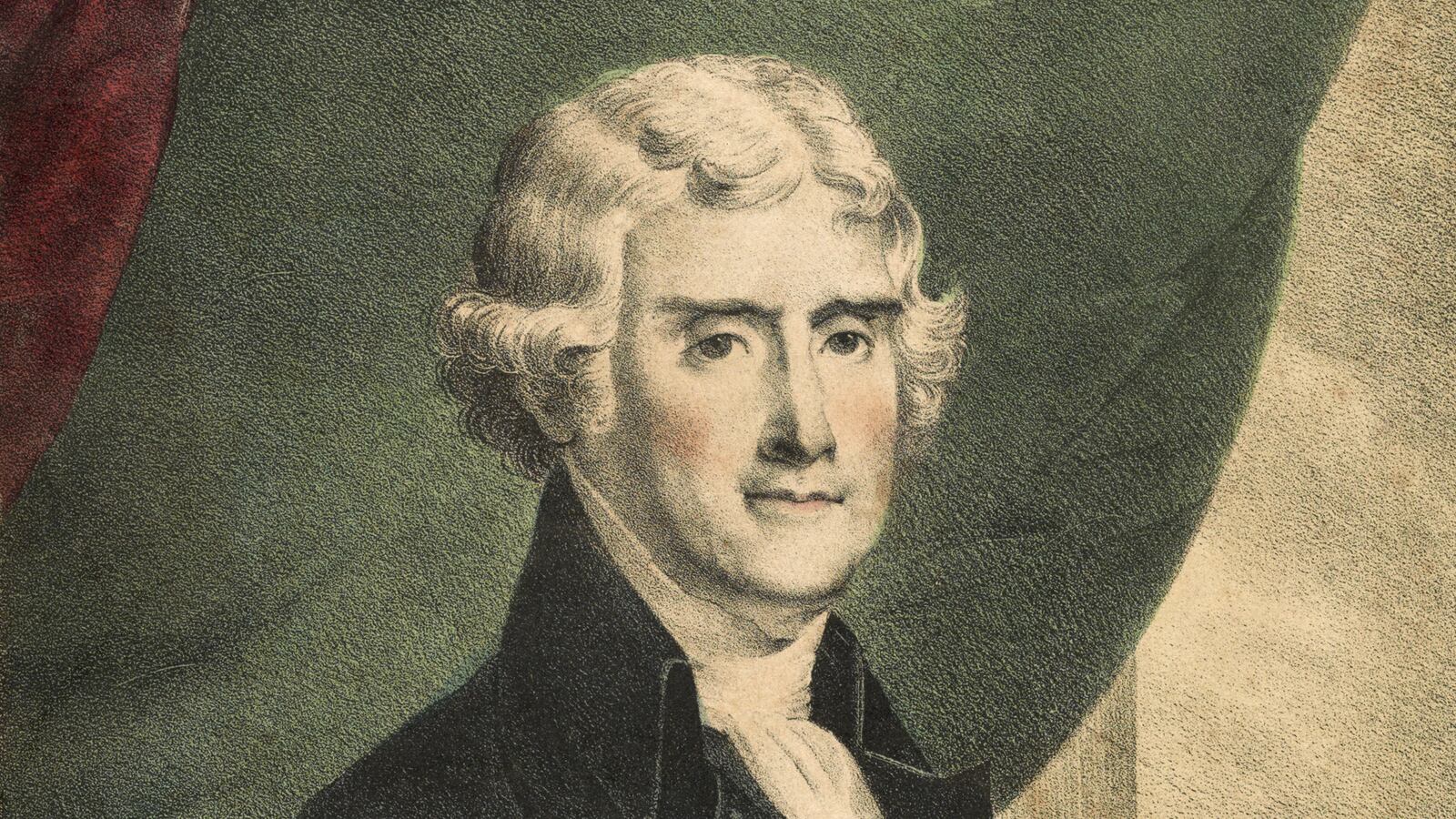

Our hardest problem is Thomas Jefferson, who kept slaves, had children by one of them, and as his biographer Fawn Brodie notes, freed only five of his slaves in his will. As C. Vann Woodward observed of Jefferson in his classic study, The Burden of Southern History, “After all, it fell [to] the lot of one Southerner from Virginia to define America.”

On the eve of the Civil War Lincoln summed up the Jefferson he revered in an 1859 letter in which he wrote, “All honor to Jefferson—to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times.”

But the Jefferson whom Lincoln admired and the nation honors in Washington with a memorial was far from consistent in his views on slavery and race.

In his 1785 Notes on Virginia Jefferson had no doubt that in their reasoning the slaves were “much inferior” to whites. “Never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration,” he writes in an entry in which the racism is unmistakable.

To his credit, Jefferson did not fool himself into believing that white-black differences justified slavery. “Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever,” Jefferson observes later in Notes on Virginia when he thinks of slaves and their masters.

What Jefferson would not do, though, was risk his personal comfort as a slave owner or his status as a politician to demand the end of slavery.

“You know that nobody wishes more ardently to see an abolition not only of the trade but of the condition of slavery,” Jefferson writes to Jean Pierre Brissot de Warville, a French friend, in 1788. But in the same letter he defends his reticence on the subject by observing that “those whom I serve having never yet been able to give their voice against this practice, it is decent for me to avoid too public a demonstration of my wishes to see it abolished.”

Decades later, with the country more deeply torn by the slavery question, Jefferson was still cautious, even though his fears had increased. Freeing the slaves scared him more than keeping them in bondage.

In 1820, the year of the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, Jefferson still would not call for the end of slavery. In a figure of speech that likens the slaves to wild animals, he writes, “But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

These contradictions in Jefferson are understandably not part of his memorial in the Capital. Only his inspiring thoughts appear in the quotations engraved on the Jefferson Memorial walls. When on April 13, 1943, the 200th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth, President Franklin Roosevelt dedicated the Jefferson Memorial, he remarked, “Today in the midst of a great war for freedom, we dedicate a shrine to freedom.” Like Lincoln, Roosevelt focused only on the side of Jefferson that inspired him.

In the midst of World War II, with D-Day more than a year way, FDR could not be expected to do better. But today we can. The only question is how we go about it. Jefferson famously referred to the slavery question sounding “a fire-bell in the night.” The murders in Charleston have become our racial fire bell.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Every Army Man Is with You: The Cadets Who Won the 1964 Army-Navy Game, Fought in Vietnam, and Came Home Forever Changed.