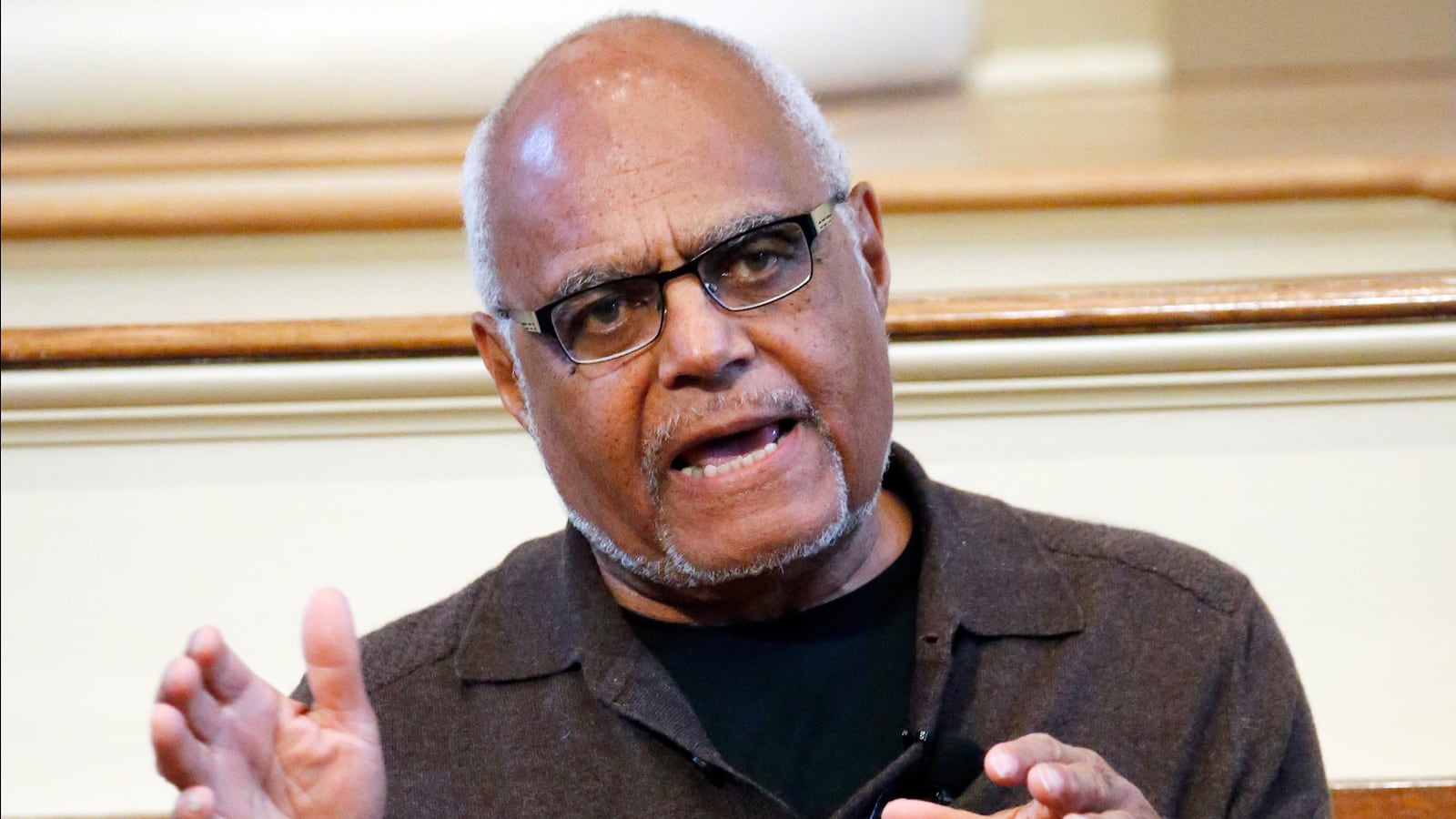

On January 24, Bob Moses will be honored with an 80th birthday party in Cambridge, Massachusetts, his home since 1976. In contrast to Martin Luther King Jr., whose January birthday is a national holiday, Moses is not widely known for his role in the civil rights movement. He should be. He was the driving force behind the historic Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964.

Unlike the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery Voting Rights March, Freedom Summer was not a short-term undertaking in which massive crowds were crucial for success. Freedom Summer lasted from June to August and depended on a black-white alliance working together on a series of planned, civil rights projects.

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), an amalgam of civil rights groups, of which the most prominent was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), provided the leadership for Freedom Summer. Volunteers, primarily northern college students, were in turn the foot soldiers for Freedom Summer.

The volunteers, who numbered under a thousand, taught in Freedom Schools designed to supplement the meager educations of most black children in Mississippi, helped register black voters, and lent their support to the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as it sought to unseat the segregated Mississippi Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City.

From the outset, Freedom Summer faced the hostility of a state in which Governor Paul Johnson Jr., considered a political moderate, prided himself in saying that the initials of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stood for “Niggers, Alligators, Apes, Coons, and Possums.”

Those who took part in Freedom Summer, whether they came from inside or outside Mississippi, paid a steep price for doing so. Three Freedom Summer workers—James Chaney (a black Mississippian), Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman (white Northerners)—were killed in June shortly after arriving from their Freedom Summer orientation session in Ohio. In August their bodies were found buried in an earthen dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi, and by the end of Freedom Summer, COFO would report four additional shootings, 52 serious beatings, and 250 arrests.

But long before “The Whole World Is Watching” became the slogan of the antiwar movement, Freedom Summer showed how the media, particularly television, could be mobilized to expose longstanding social problems. The president and the FBI became involved in Mississippi as a result of the publicity surrounding the murdered Freedom Summer workers. Previously unregistered black Mississippians made it onto voter rolls that they had been kept off for years, and the Democratic National Convention, although it never seated the Freedom Democratic Party, rewrote its rules so that segregated delegations were banned from future conventions.

“When you come South, you bring with you the concern of the country—because the people of the country don’t identify with Negroes,” Moses told the predominantly white volunteers during their summer orientation session. The volunteers’ presence, he correctly believed, would put a spotlight on the racial violence white Mississippians felt they could get away with—and did get away with. Seven of the men responsible for the deaths of Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman were eventually sent to prison in a case brought by the Justice Department.

Since 1960, Moses had been a presence in rural Mississippi, working on voter registration, seeking out the young Mississippians who would become the backbone of a home-grown, voter-rights movement, and it was during this early period, when few outside of the civil rights movement were interested in Mississippi, that Freedom Summer had its genesis.

As Moses later observed in Radical Equations, the book he co-wrote with journalist and civil rights activist Charles Cobb Jr., “The great campaigns of protest so identified with Martin Luther King Jr., were swirling around us, inspiring immense crowds in vast public spaces. But along with students from the sit-in movement, in Mississippi I became immersed in and committed to the older but less well-known tradition of community organizing.”

For Moses the key to community organizing was not being the most spellbinding orator in the room. The key was being the organizer who helped future civil rights leaders find their own voices. As he later observed during a tribute to Ella Baker, the veteran civil rights worker who played a crucial role in the founding of SNCC, “You don’t have to worry about where your leaders are… The leadership is there. If you go out and work with your people, then the leadership will emerge.”

In a 1961 letter that he wrote after being put in the Magnolia, Mississippi, jail for his part in a voter registration drive, Moses described the challenges he faced in Mississippi in prose that was a match for the bib overalls and white T shirt he so often wore at the time. In its concreteness and detail, Moses’s letter is very different from Martin Luther King’s more famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” with its memorable declaration, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

In his letter Moses did not offer an overview of the civil rights movement or theorize about its future. Instead, he evoked the vulnerability of himself and those with him in the Magnolia jail, even as he saw their presence as a crack in the edifice of segregationist Mississippi. “Twelve us are here, sprawled out along the concrete bunker,” Moses wrote. “We lack eating and drinking utensils. Water comes from a faucet and goes into a hole. This is Mississippi, the middle of the iceberg… This is a tremor in the middle of the iceberg—from a stone that the builders rejected.”

Today, King’s and Moses’s jail letters are as moving and significant as when first written, but we have given the author of only one of them his full due. That needs to change. Moses, who has now lived more than twice as long as King, has not used the time since Freedom Summer to romanticize the ’60s or the role he played in them. “I’m really lucky that way,” he says when he talks of how he managed to survive the beatings and shootings he experienced in Mississippi.

After Freedom Summer ended, Moses became involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement, and since 1982, when he received a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, he has devoted himself to developing the Algebra Project, a nationwide effort to teach poor and minority students math and science.

Convinced that students without a knowledge of math and science are destined to be “serfs of the information age,” Moses sees the Algebra Project as an extension of the goals of Freedom Summer. “I believe that the absence of math literacy in urban and rural communities throughout this country is an issue as urgent as the lack of registered Black voters in Mississippi was in 1961,” he wrote after starting the Algebra Project. “And I believe that solving the problem requires exactly the kind of community organizing that changed the South in the 1960s.”

Moses does not underestimate the enormous problems currently facing the Algebra Project and its offshoot, The Young People’s Project, but now, as in Mississippi, he remains an organizer with the temperament of a long-distance runner.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America.