In late February at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, Remy Ohara, a UCLA music student, sounded a shofar, the ram’s horn usually used for High Holiday services at Jewish temples—first in short blasts, then longer sustained tones. Surrounded by a brass and percussion orchestra and flanked by two sections of a large choir, she held the shofar aloft. I was struck by the image of her instrument, directly beneath the large cross affixed to the front wall of Holman church, where, just three weeks before his assassination in 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a sermon about the meaning of hope.

Thus began a performance of The Gates of Justice, a 12-movement cantata composed by Dave Brubeck in 1969. The work was originally commissioned by a rabbi, Charles Mintz, to premiere at the dedication of the Rockdale Temple in Cincinnati, Ohio. Yet it had a deeper, broader intent: to help heal the wound opened during a period of pronounced violence and unrest following King’s death and, specifically, to repair a growing rift between American Black and Jewish communities—rooted in racism, antisemitism, class privilege and historically unequal partnerships, among other factors—where there had previously been common cause in fighting social injustice.

A performance of “The Gates of Justice” at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles on Feb. 28, 2023.

Juan Tallo“The essential message of The Gates of Justice is the brotherhood of man,” Brubeck wrote in his note to the 1970 Decca LP of the piece. (That recording is now out of print; in 2001, the Milken Archive of Jewish Music, founded by the businessman Lowell Milken, recorded the work for Naxos.) “Concentrating on the historic and spiritual parallels of the Jew and the American Negro, I hoped through the juxtaposition and amalgamation of a variety of musical styles to construct a bridge upon which the universal theme of brotherhood could be communicated.”

To that end, Brubeck composed the principal vocal roles for a tenor, in Jewish cantorial fashion (sung in Los Angeles by Azi Schwartz, a cantor at New York City’s Park Avenue Synagogue) and a baritone, drawing on Black Spirituals and blues (sung here by Phillip Bullock). The piece includes among its textual sources, the Bible, the writings of the Jewish sage Hillel, and excerpts from King’s speeches, all compiled and shaped primarily by Brubeck’s wife, Iola, who was his frequent collaborator.

Musically, the piece’s 12 movements include complex sections that grow raucous, as well as more meditative ones in which vocals seem to evaporate into air. The music evokes both sacred and secular styles. There is, early on, a lovely Bach-style chorale, and sections based on the characteristically Jewish, so-called “Freygish scale” as well as on blues chord progressions. There are stark, sometimes rapid-fire allusions to pop, rock, and Latin music as well as Chopin Preludes, and a final movement based on the “tone rows” once championed by composer Arnold Schoenberg. And there is swinging jazz with improvised interludes. These sections were originally played by a trio led by Brubeck. In Los Angeles, they were performed by a trio of his sons: pianist Darius (named for Brubeck’s clearest musical mentor, composer Darius Milhaud); drummer Dan; and Chris, who played both electric bass and trombone.

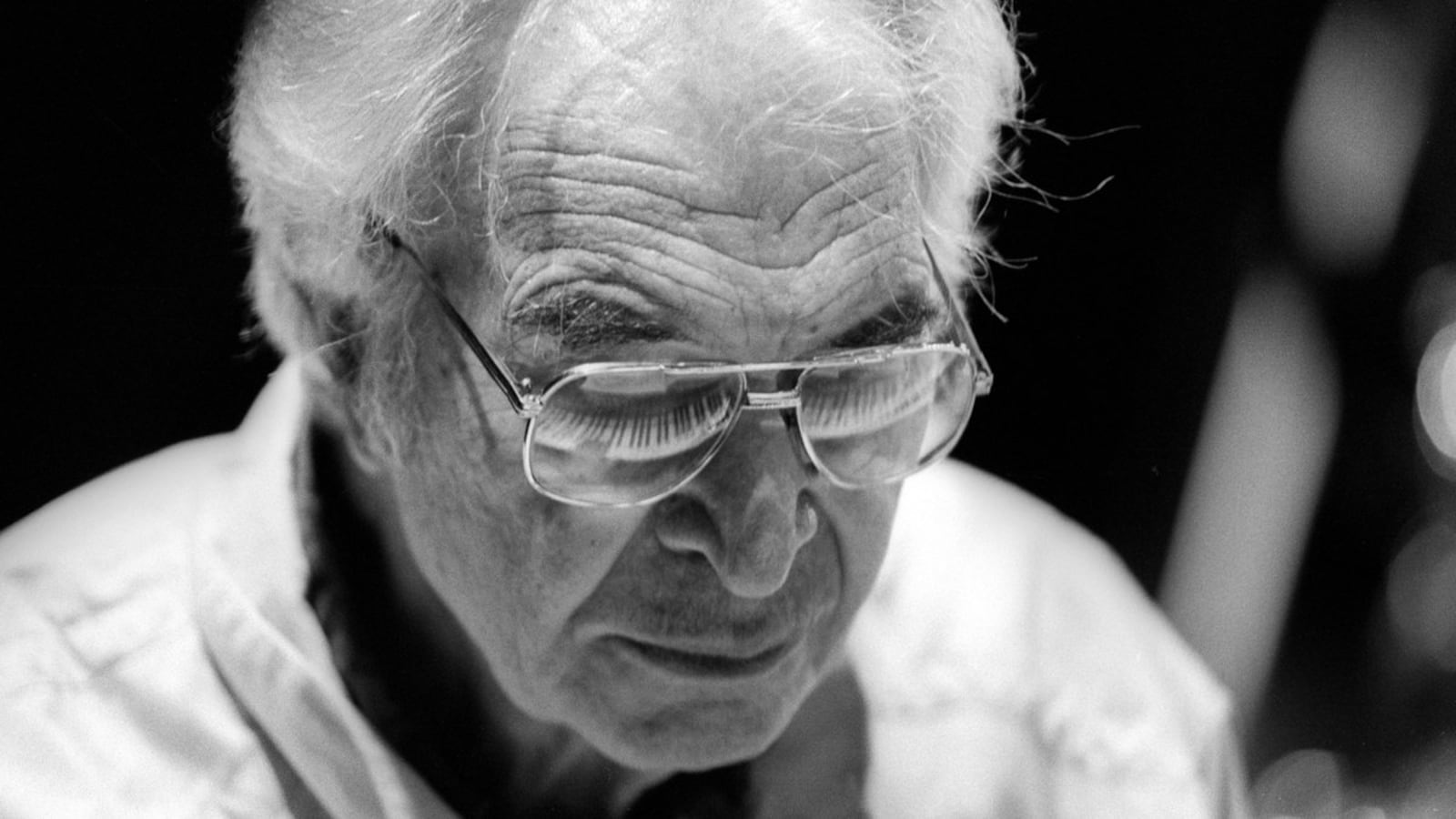

Dave Brubeck, of course, became a household name more than a half-century ago on the strength of his popularity as a jazz pianist, composer, and bandleader. Long before he composed The Gates of Justice, he achieved a level of fame known by few American musicians. He made the cover of Time magazine in 1954. Five years later, his quartet recorded Time Out, the first instrumental jazz album to sell 1 million copies. And Brubeck’s image is quintessentially American in many respects: He grew up a cowboy-in-training, riding horses on a Concord, Calif., cattle ranch; served in Gen. George S. Patton’s army in World War II; displayed ingenuity with the odd-metered swing of his early hits; and was tapped by President Eisenhower to represent Democratic values to Soviet-bloc nations.

Brubeck’s commitment to social justice and his commentary upon it long predate this piece. In 1960, at the height of his popularity, he canceled a lucrative tour of Southern colleges because the promoters objected to the presence of bassist Eugene Wright, who was Black. The decision cost Brubeck a great deal of money and made headlines. “I’d be selling these kids short to go down South with an all-white group,” Ralph Gleason quoted him as saying in a 1960 Down Beat magazine piece. “We simply couldn’t consider it. It would be morally, religiously, and politically wrong. Prejudice is indescribable. To me it is the reason we could lose the whole world.”

Around the same time, Dave and Iola Brubeck created “The Real Ambassadors,” a “jazz musical” starring Louis Armstrong, which made a powerful statement against the hypocrisy of a government that sent jazz musicians abroad to extoll the virtues of American democracy in the face of racism at home (and which, uniquely for its time, cast Armstrong as a proud Black man rather than a crowd-pleasing caricature). Brubeck told his biographer Philip Clark that it was “a satirical show. Through laughing at such a situation as racism, we bring it down.”

By 1969, after Brubeck’s classic quartet disbanded, he began composing classically oriented and choral works, all of which took as subjects social justice, morality, and spirituality. That year, he told a Washington Post reporter, “I think I can reach more people with what I think is important now—at this time in my life, and at this time in our history through this medium.” That focus would continue until his death in 2012, at 91. The first of these, 1968’s The Light in the Wilderness adapted biblical texts to contrast the teachings of Jesus with the horrors and hypocrisy that he witnessed firsthand during World War II. He followed The Gates of Justice with another cantata, Truth Is Fallen (1972), in response to the killing of student protesters at Kent State University in 1970.

‘They Damn Well Better Hear It’

In 2004, in connection with a San Francisco presentation of The Gates of Justice, I interviewed Brubeck at his Wilton, Connecticut, home. He spoke movingly of early awakenings about the history of racial conflict in the United States: how his father once asked a Black friend to open his shirt, revealing a chest that had once been branded; how the “Wolf Pack,” the band Brubeck led to entertain front-line GIs, “might have been the first integrated unit in World War II”; how easily he made the decision to cancel that 1960 tour (“I found out that the teachers and the presidents of the universities wanted us,” Brubeck told me, “but they were afraid of losing their government support.”) “I was thrilled to hear the similarities between Hebrew chant and Spirituals and blues,” he told me of his experience composing The Gates of Justice.

I asked how he thought the piece would be received all those years later, and what his hopes were for its presentation. “We’ll see,” he said, and then paused before going on. “You know, when Dr. King said, ‘We must live together as brothers,’ people didn’t hear it. Now they damn well better hear it. In this piece, that’s what I’m talking about.”

I was pretty sure that’s what Dave Brubeck would have said in late February. “That’s exactly what he would say,” Darius, the eldest of Brubeck’s sons, told me in Los Angeles. We had all been invited by UCLA’s Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music, which had mounted performances of The Gates of Justice at the university’s Royce Hall as well as at the Holman church; in between, the center hosted a day-long conference, “Music and Justice: A Dialogue Through Thought, Creativity and Music.”

We now find ourselves in another especially divisive moment, one in which racism and antisemitism are newly potent and weaponized, in which those same bonds of concern to Dave Brubeck in 1969 are again getting torn apart. For Mark Kligman, the center’s director and a professor of ethnomusicology and musicology, the idea of a fresh context for Brubeck’s piece offered one way to address present-day ills.

Darius Brubeck told me, “In a way, my parents believed—and had a right to believe—that when Obama was elected, a goal had been achieved, a corner was turned. But my parents didn’t live to see what has come since. It doesn’t matter: The principles on which The Gates of Justice is built and its message are non-negotiable. Dave and Iola were saying and would say now, ‘This is what we believe, what we’ve been taught to believe, and we invite you to see how everyone would be better off with true justice.” Not long before Dave Brubeck composed that piece, Darius, then a college senior, had traveled to Mississippi to volunteer for voter registration drives. “There’s a need to restate that particular struggle for justice,” he said, “for people who don’t remember it.”

The first half of each concert in Los Angeles reframed the very words and deeds of that struggle through contemporary pieces, some of which were composed specifically for the event. The poetry of Langston Hughes formed texts for three works from composers Joel Thompson, Jared Jenkins, and Arturo O’Farrill (the latter, a world premiere based on Hughes’ “I Dream a World”). Hardest-hitting of all was “Dear Freedom Riders,” a piece composed by Diane White-Clayton, who is on the faculty of UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music. Its text was compiled from letters White-Clayton invited the student musicians to write to the Civil Rights activists who famously rode interstate buses into Southern states in 1961 to protest the unconstitutional segregation.

“When you look at today’s America, what do you see?” one lyric asked. “Have we softened? Are we complacent?” The effect of this was deepened greatly at the Holman church concert by the presence of Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely, a poet and member of Holman church, who was among those Freedom Riders, and who had been jailed for her work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The original poem she recited to White-Clayton’s piano accompaniment, “Just Leaving: 1961,” was elegant yet also brutally stark in its details: “When the boy spit / When the siren screeched / When the sheriffs came / When the handcuffs cinched.”

At the conference in between the two concerts, scholars mined the inspiration for Brubeck’s composition, his manner of creative expression, and the contemporary context for its themes. Hasia Diner, author of several books on American Jewish and immigration history, talked about social and political alliances between Black and Jewish communities, but also histories for each group in this country that “couldn’t be more different.”

Kelsey Klotz, whose recently published book Dave Brubeck and the Performance of Whiteness includes enlightening reporting and analysis on The Gates of Justice, discussed in detail Brubeck’s Third Movement, which begins in an agitated state, with a percussive chant to “open the gates,” and then moves to a Bach-style chorale, “as a way of saying, ‘Here is how we could work together to open the gates of justice.’” And yet, she pointed out, Brubeck inserts “harmonic ambiguity” into what would otherwise be a consonant and triumphant moment, as if to say, “We’re not there yet.’”

Dwight Andrews, an Emory University professor who is also a pastor, composer, and saxophonist, spoke of the importance of bringing Brubeck, who despite his popularity has been largely overlooked by scholars, “back into the literature.” He’s working on a book about the connections between spirituality, religion and jazz, in which he’ll consider Brubeck alongside the likes of Duke Ellington, Mary Lou Williams, and John Coltrane. “We have secularized our understanding of the Civil Rights Movement,” Andrews said. For him, Brubeck’s setting of King’s words in this context help remind us of the inseparable bond between faith and action that helps guide both morality and activism. Brubeck’s deft combinations of musical styles mirror what we now term “intersectionalities” that help us understand the nuances of identity. And in his 12th and final movement, which Brubeck built on “tone rows,” Andrews hears both advanced musicological development and a simple statement of inclusion—an accessible melody that moves through all 12 tone rows, implying “all of the people.”

At the conclusion of each concert, as an encore, the three Brubecks—Darius, Chris and Dan—returned to the stage to perform “Blue Rondo à La Turk,” one of their father’s best-known compositions, which displays his brilliance at floating a melody based on a 9-beat phrase atop what is essentially a 4/4 blues. Aside from their mastery was the sheer buoyancy of their joy, like brothers cutting loose on a favorite tune in their garage. After a grand and more profound statement of “brotherly love” as Jesus and King had meant it, here was a literal, palpable expression of the familial variety.

Music without category

Was it a coincidence that the celebratory dinner that evening was held in the “Optimist Room” within a campus conference center? Earlier, Andrews had described The Gates of Justice not as testimony of individual religious experience but rather “a sermon of sorts—a narrative, a prayer through darkness, toward light.” At dinner, Chris Brubeck explained that, for all his musical sophistication, Dave Brubeck was, “in a way, like an American primitive folk artist. He’s so damn sincere that it just kills you, and you end up changed.” No less sincere and affecting was Chris’ stirring trombone solo in his father’s Fourth Movement that night. Earlier, Dan Brubeck recalled for me the memorial after his father’s death. Eugene Wright, the bassist, pulled him aside. “He told me that my dad was one of the few guys who put their money where their mouth was, literally, who refused to do anything that went against his moral principles. All those years later, that’s what he remembered more so even than the music.”

Neal Stulberg, whose deft conducting lent cohesion to the orchestra, choir, and jazz trio, considers The Gates of Justice a “living work,” whose musical elements are open to some interpretation. (In Los Angeles, some of the musical references—“Jarabe Tapatío,” [or “Mexican Hat Dance”], for instance—were excised from Movement Ten; the racial epithets meant to be shouted in Movement Five were replaced by cacophonous choral outbursts.) But the meaning, he said, never changes. “Through an ingenious integration of texts, voices, and instrumental techniques,” Stulberg said, “he managed to create music without category, that represents both interfaith expression and social activism.”

Dave Brubeck, who was neither Jewish nor Black, was nevertheless perhaps especially well equipped to negotiate a divide that widened in the 1960s and seems widening once more in dangerous fashion, simply because he was, throughout his career, a seeker regarding musical and spiritual matters. Mark Kligman thinks The Gates of Justice helps define the mission of the Milken Center, and that the piece’s larger message is more urgent and necessary now than perhaps even when Brubeck composed it. His hope in presenting it anew was for it to “be that lightning rod, that spark, for a very important conversation.”

That’s what Dave Brubeck was talking about in 1969, and what his legacy demands today.