If you purchase something from our posts, we may earn a small commission.

The 1990s is a decade bracketed by two cataclysmic events: the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the fall of World Trade Center in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. During the brief period between these events, Americans felt safe from dangers abroad. Neither the collapsed Soviet Union nor a China on the rise could, it seemed, harm us.

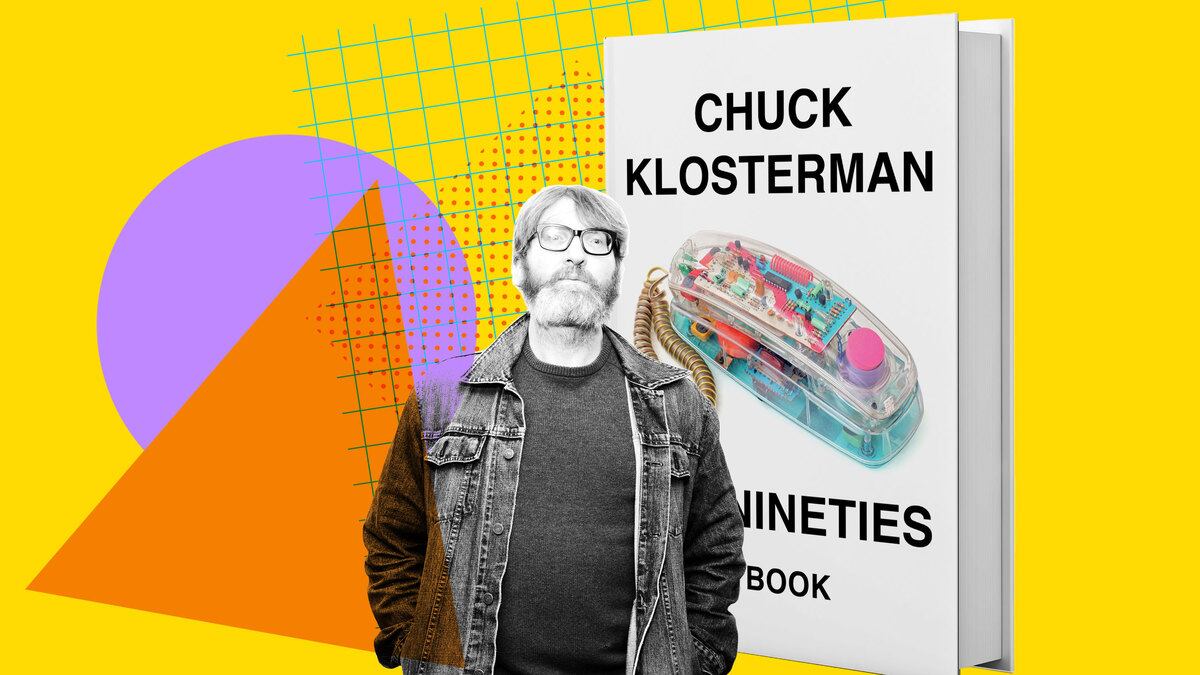

Today, with Vladimir Putin’s Russia threatening Ukraine and Xi Jinping’s China threatening America’s economic self-sufficiency, it is easy to sentimentalize the 1990s as the last great American era. As Chuck Klosterman writes of the decade in his new book, The Nineties, “Communism, and whatever threat it allegedly posed, was over. There was only one superpower remaining, and that was the U.S.”

Why did the United States not do more at home and abroad in this period of relative calm to make life better for itself and rest of the world? It is a question that lies at the center of The Nineties and one that Klosterman, a wide-ranging writer, is well-suited to answer. He has published fiction and nonfiction, been a music journalist, and served as Ethicist for The New York Times Magazine.

“It was, in retrospect, a remarkably easy time to be alive,” Klosterman says of the ’90s. “The United States experienced a prolonged period of economic growth without the complications of a hot or cold war, making it possible to focus on one’s own subsistence as if the rest of society were barely there.” The internet was coming, but it had not arrived with full force. In 2001, daily newspaper circulation was 55.6 million, roughly what it had been for the 40 previous years.

Klosterman is most revealing when he explores what underlies an event or a person we think we knew. He explains how the triumphal Gulf War that President George H. W. Bush led in 1991 did not, as Bush expected, work to his political benefit. When voters remembered the Gulf War, they thought of Norman Schwarzkopf, the burly general who commanded Allied forces, and Colin Powell, the cool chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Being associated with them worked to Bush’s detriment, Klosterman points out. In their presence, “Bush devolved into a milquetoast figure no one wanted.”

With equal finesse Klosterman explains how Friends, the popular CBS sitcom about six twentysomething college grads living in New York City managed to last 10 years despite seeming to be about nothing more substantial than the group’s dating problems. The show, which began in 1994, captured in a way that was reassuring to its audience, Klosterman observes, the reluctance of Generation X (those born from 1965 to 1980) to get bogged down with raising children or tied to an all-absorbing job.

There are more than enough of these insights in Klosterman’s book to hold our attention as he swiftly moves from topic to topic. The problem is that the collage-like organization of The Nineties is also a weakness. The book does not have a clear chronology, nor is it based on chapters that take on a single topic in depth.

It is hard to know the basis for inclusion and exclusion in The Nineties. When it comes to literature, David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest and Elizabeth Wurtzel’s memoir Prozac Nation gain Klosterman’s attention, but Philip Roth, whose writing flourished in the 1990s but who was not, like Wallace and Wurtzel, a Gen Xer, gets no mention despite the scope of his literary career. Similarly, there is no mention by Klosterman of the landmark 1992 case of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey in which the Supreme Court upheld a woman’s fundamental right to abortion as guaranteed in Roe v. Wade but also said a state had a right to regulate abortion if it did not impose an “undue” burden on a woman.

The result is that, when we get to the end of The Nineties, we are unsure if we have the full story despite the material that Klosterman has assembled. That’s too bad, because what his book makes clear is that time and again the ’90s offered a preview of issues that would become more extreme in the new century.

A case in point: the 1992 beating of Black motorist Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers after a high-speed chase. The officers were acquitted by a state jury on assault charges despite a videotape of them hitting King with their batons as he lay helpless on the ground. Nearly three decades later that beating and acquittal were still very much part of public memory when George Floyd, another Black victim of police brutality, died in 2020 at the hands of Minneapolis police following his arrest for cashing a counterfeit $20 bill. This time the police officer directly responsible for Floyd’s death received a lengthy prison sentence. The current result is an improvement over the King verdict, but what has not followed is what is most needed: nationwide police reform.

A similar link between past and present holds for the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center in New York City and the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City by Timothy McVeigh, a decorated military veteran. In the first case, a van loaded with 1,300 pounds of urea nitrate was used. In the second case, a rented van containing 5,000 pounds of explosives was the weapon of choice. The deaths—seven at the World Trade Center, 168 at the Alfred P. Murrah Building, were tragic, but far short of the nearly 3,000 deaths that resulted from the 9/11 attacks. The lesson that should have been learned in the ’90s—the government needed to recalibrate the way it kept ordinary citizens safe from foreign and domestic terrorists—never got through.

Had we thought more deeply about the ’90s while the decade was occurring, might life be better for us in the 2000s? It is comforting to think so. From our current vantage point, the ’90s seems like an age of both lost innocence and lost opportunity—claims we would never make about the present.

The Daily Beast has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though we may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links.