This story was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter here.

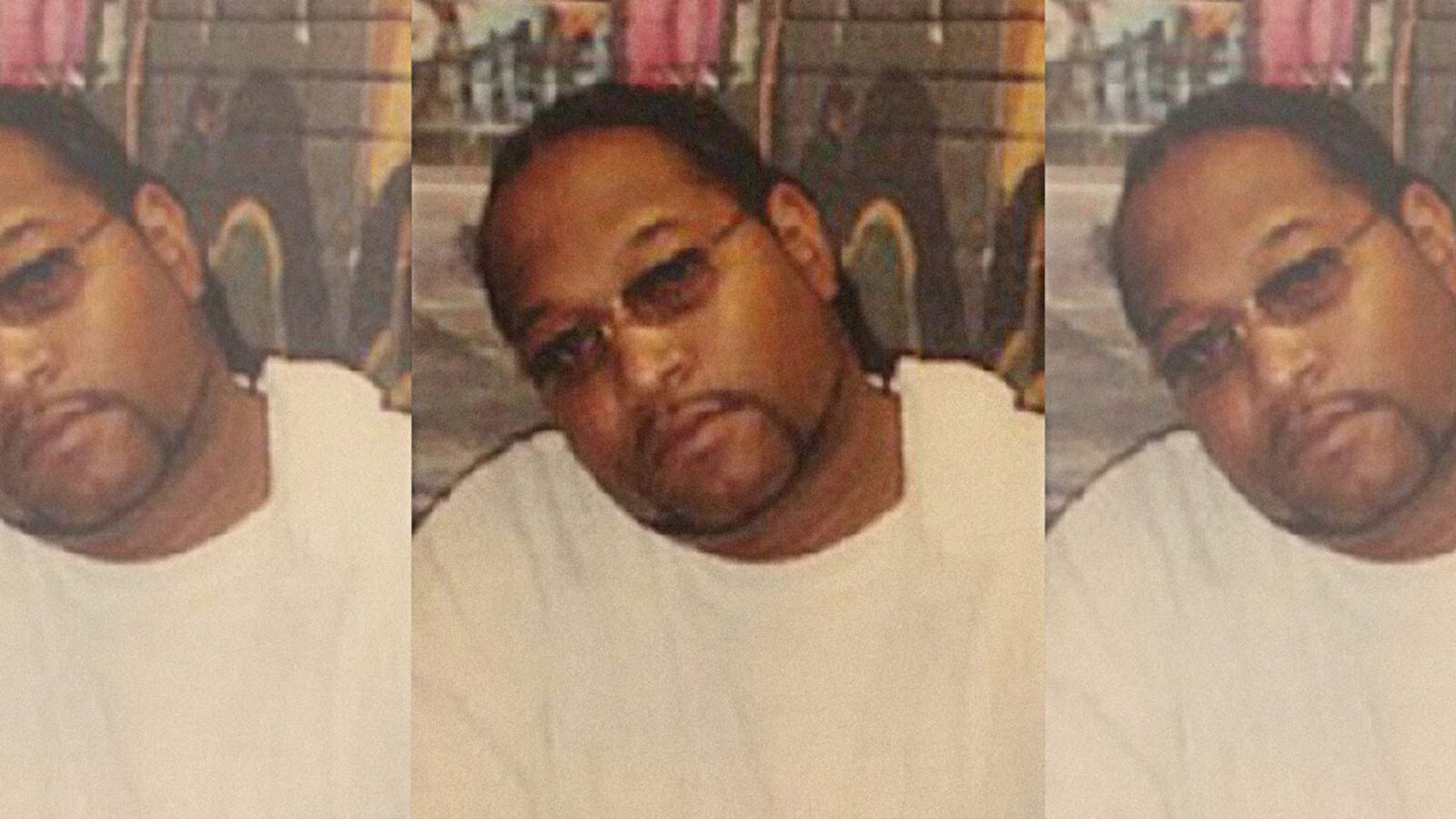

When Patrick Jones called his family members from a federal prison in Louisiana, he’d talk about how hard he was trying to get out. He wanted to return to Texas and open a restaurant, serving everything from tacos to brisket to soul food. He’d even learned to make pastries while inside.

But most of all, he was worried his own son might be on the path to prison, and, having spent so much of his own adult life in and out of trouble, he wanted to get out in time to intervene. “Patrick’s goal was to get out to try to stop him from living that type of lifestyle,” recalled Jones’s stepdaughter, Lateasha Crumpton-Scurry.

Jones was serving 27 years for selling cocaine in Temple, a small city between Austin and Dallas, in 2007. Over the last year, his lawyers had been asking a federal judge to let him out under the new terms of the First Step Act, the bipartisan criminal justice reform bill signed by President Trump. “Patrick deserves another chance at life,” one lawyer wrote. The judge denied the request, but Jones told his family he would appeal.

“I could hear in his voice that he was very hurt,” said his sister, Debra Canady. “But he always stayed strong towards me.”

On March 28, Jones became the first federal prisoner to die due to complications from COVID-19, according to a Bureau of Prisons press release. He was 49. He was the first of five prisoners who have died after contracting the coronavirus at FCI Oakdale I, a federal prison in Louisiana that holds nearly 1,000 men. The virus has spread so extensively in the facility, according to The Lens, that those who show symptoms are no longer being tested.

Even as prisons around the country cancel family visits and classes, they continue to house large numbers of elderly and otherwise vulnerable people. U.S. Attorney General William Barr has ordered officials to release some federal prisoners, but his plan has been criticized for potentially excluding people with prior arrests, many of whom tend to be black. The debate over whom the government should release during this health crisis mirrors years of political wrangling under both Obama and Trump over who deserves a second chance and who is likely to commit further crimes.

Although it’s unlikely Jones was ever personally mentioned in the halls of power, he was the kind of person these debates were about.

“His case is exactly the type of case we’ll need to grapple with,” said Kevin Ring, president of the advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums, pointing out that Jones was not a first-time drug offender, but also wasn’t the “repeat violent offender who will never change.” Still, Ring, who himself is formerly incarcerated, considered Jones’s sentence of 27 years excessive: “He was killed before the coronavirus killed him, because that sentence was absurd.”

Much about Jones’s early life is shrouded in mystery, even to some close relatives. Canady, who is 16 years younger, said they were not biologically related, although they considered one another brother and sister. “His grandmother died when he was 6, and he shuffled between relatives and the street for the rest of his childhood,” wrote his former lawyer, Alison Looman, in October 2019, as she asked a judge to see him as deserving release. “By the age of 16, Patrick started engaging in petty crime. Given the lack of structure or support during his childhood, this may not be totally surprising.”

At the same time, Jones’s family members said they saw another side to him, that he maintained legal employment as a handyman who also took care of lawns. “He loved to fix up cars,” said Canady, recalling how they’d drive around in a black Cadillac he’d refurbished. He seemed to always be moving. “He’d always put us to work: ‘Hey, go plant this rose bush.’” He was known to experiment in the kitchen, according to family members, which led to the nickname “Chop Chop.”

Around 2001, he fell in love with a woman who had moved to the Temple area with several children from Alabama, and they had a son together. “His childhood made him want more, want better for his kids,” Canady said.

Jones’s stepdaughter, Lateasha Crumpton-Scurry, said she never remembers any sign of his illegal activities at home. She suspected they were in part an effort to provide for his growing family — he had several kids of his own, along with the stepkids — after years of feeling alone. “He really didn’t have anybody to turn to,” Crumpton-Scurry said.

She said he kept up with her mother even after he was locked up briefly around 2005. They split and he remarried. Then, in 2007, Jones was arrested after a Temple police officer, while looking for a different person in apartment, found a tool used to clean a pipe after smoking crack cocaine. Jones had been convicted of burglary nine times (all stemming from a spree when he was 17, according to one of his lawyers), as well as selling drugs, and had a warrant out for his arrest because he’d violated his parole conditions. The officer searched the apartment, finding 23.1 grams of crack cocaine, according to court records, and 21.4 grams of powder cocaine.

Jones’s wife testified at his trial that together they manufactured and sold the drugs, and based on her account, prosecutors charged him with 425.1 grams of crack cocaine, even though this vast quantity was never found. (After testifying, his wife received three years of probation.) His sentence was also increased because they lived within 1,000 feet of a junior college. His projected release date was Aug. 9, 2030, followed by five years of supervision.

The length of his sentence could be traced in part to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, crafted by then-Sen. Joe Biden, which vastly increased mandatory minimum sentences for crack cocaine versus powder cocaine. This provision was later criticized for disproportionately punishing African-Americans. “The road to hell is paved with good intentions,” Biden later said.

Jones went to prison just as federal lawmakers were beginning to rethink such long prison sentences for drug crimes. A year into his sentence, Congress reduced (without eliminating) the disparity between crack and powder cocaine. Eventually, Obama went further, announcing that he would personally intervene to free numerous federal prisoners by granting them clemency. Jones was among the applicants.

Although he did receive several disciplinary infractions inside prison, court records suggest that by 2016, with a much longer sentence than he’d ever served previously, he had turned his life around. (Criminologists often speak of people “aging out” of crime.) “Productive worker,” a supervisor wrote about his job sewing buttonholes on shirts. He studied for his GED and took classes with names like “Five Secrets to Finding a Job” and “Ticket to the Future.” From prison, he sent family members pictures of men whose hair he had braided. “My brother has learned from his mistakes,” his sister Canady wrote.

One son, who he had last seen as a toddler, was now a teenager. “I’m worried my son will follow down the wrong road his father did,” his mother, Claudette Crumpton, wrote to President Obama, who had made “responsible fatherhood” a focus of his administration. “The talks they have when he calls hurts me as a mother,” she explained, “to see my child cry night after night missing his years with his father.”’

Although Obama commuted the sentences of 1,715 men and women, the most of any president in decades, the process was criticized for its slowness and arbitrariness. “Humans making decisions will not always be perfect,” White House counsel Neil Eggleston told The Marshall Project.

Jones was denied. “The timing leads me to believe it is possible his petition was not reviewed at all,” Jones’s lawyer later wrote. When she told him the bad news, she noted, “he expressed concern not for himself but for me … it is a telling example of what a kind and compassionate person Patrick is.”

Washington’s rethinking of old criminal justice laws continued as Trump took office and a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers passed the First Step Act of 2018, which made prisoners like Jones eligible for release by rendering Obama-era policy changes retroactive.

During the run-up to passage, lawmakers fought — and they continue to fight today — over whether those given a second chance might commit new crimes and whether it's necessary to include people who committed violent crimes as deserving of those chances.

Jones had re-offended in the past, as well as committed burglary as a teenager, a crime that has been considered both violent and non-violent at different times. But after Trump signed the First Step Act, Jones applied again to leave prison early. His lawyer told the court that

the new laws signed by Obama and Trump were a clear illustration that his sentence had been excessive, and that offenses he committed as a teenager were still being held against him as he neared 50.

Jones himself wrote to the court. “I feel that my conviction and sentence was also a punishment that my child has had to endure also and there are no words for how remorseful I am,” he wrote. “I have not seen him since he was three years old.” He continued, referring to his prison identification number, “83582-1800 has no meaning. It is just a number to be forgotten in time. But Mr. Patrick Estelle Jones is a very good person. Caring, hardworking, free and clean of drugs and a lot smarter now, with a balanced outlook on life.”

“He was trying to make amends,” said one of Jones’s older sons, Christopher Walker. “Everybody makes mistakes.”

Federal prosecutors opposed letting him out. “Jones was not a small-time crack dealer whose sentence far outweighed the scope of his criminal activity,” read a December 2019 response filed by U.S. Attorney John F. Bash, who pointed to Jones’s burglary and drug convictions. “He maintained a leadership role in his ‘crack’ distribution enterprise, using another person to distribute ‘crack’ for him.”

In late February, U.S. District Judge Alan Albright ruled to keep Jones in prison, calling him a “career offender” with a history of committing new crimes each time he was let out on parole.

On March 19, Jones complained of a persistent cough, according to the Bureau of Prisons press release, which noted that he had “long-term, pre-existing medical conditions which the CDC lists as risk factors for developing more severe COVID-19 disease.” He was taken to a local hospital, where he tested positive and was placed on a ventilator. He was pronounced dead on March 28.

“So many people out there are worried this is going to happen to their family members,” Crumpton-Scurry said.

A group of public defenders wrote a letter to Barr calling Jones’s death a “grim milestone” and demanding “rapid decarceration.” Since his death, four more men at the prison in Louisiana also succumbed to coronavirus complications. One was there for child pornography charges, another for an armed bank robbery and the other two for charges related to selling marijuana and methamphetamine.

Each, as they are remembered by family members and encountered by news readers, will have the details of their lives scrutinized for whether they should have been in prison in the first place.

Kevin Ring, the advocate, cautions against extreme portrayals of victims and villains. “We don’t need to make him out to be the greatest person ever,” he said of Patrick Jones, “in order to say his life has value.”