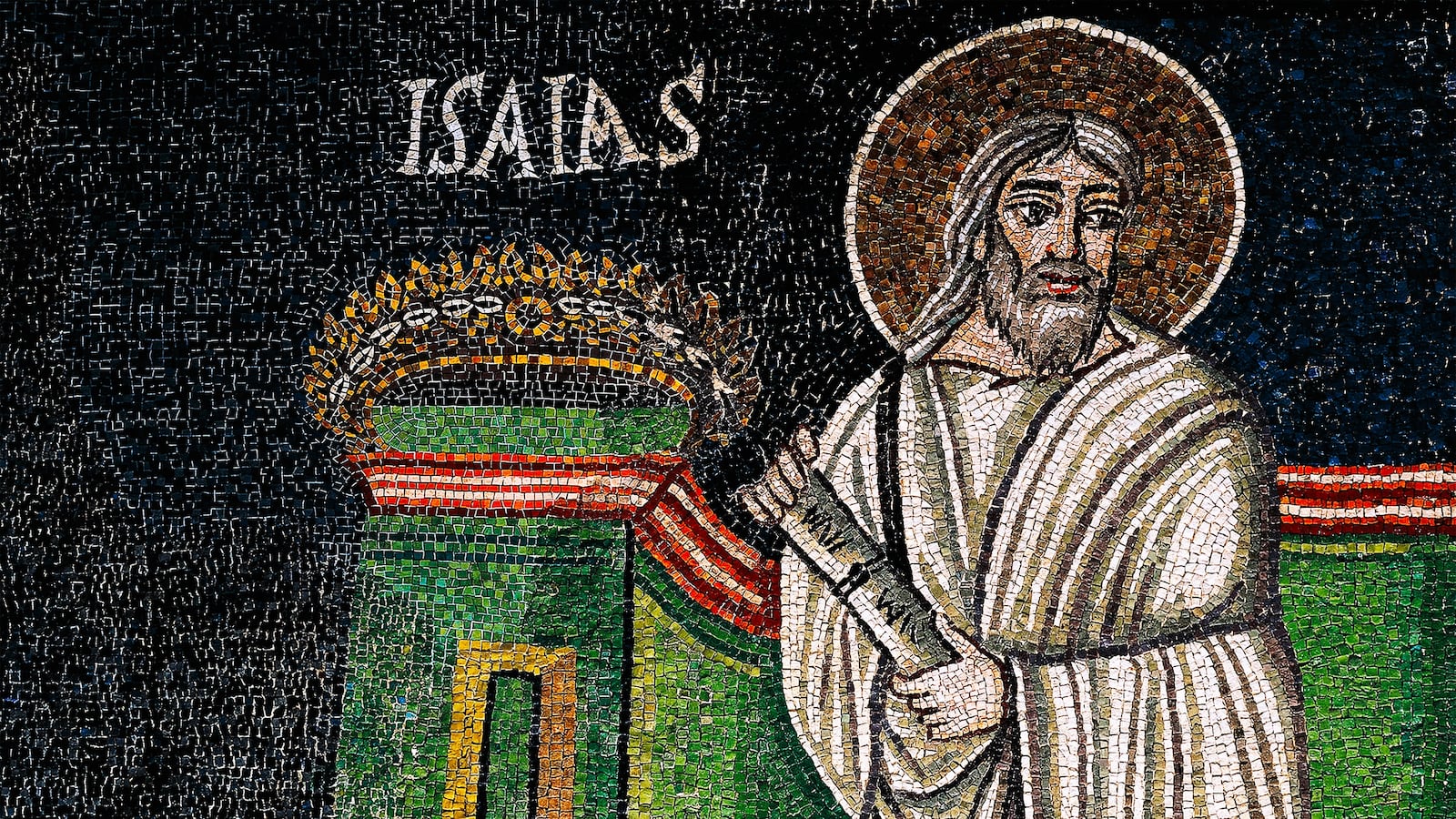

If you asked people whom their favorite biblical prophet is, there’s a strong chance they would answer Isaiah. Sure, Moses gets all the accolades, received the tablets, and is the most important; but Isaiah is the prophetic book most quoted by authors of the New Testament. For Christians, Isaiah predicts the coming of the Messiah, the death of Jesus and the Virgin Birth. So, it is particularly auspicious that in a stunning article published today in Biblical Archaeology Review archaeologists announced that they have stumbled upon the first physical evidence for the existence of the prophet Isaiah.

The evidence itself comes in the form of a small piece of clay (an impression left by a seal), a mere 0.4 inches long, which appears to bear the inscription “Isaiah the prophet.” It was unearthed as part of excavations of a previously undisturbed pile of debris at the Ophel excavation in Jerusalem. The dig is headed by Eliat Mazar, who provides a description of the discovery, significance, and translation of the seal in an article published in this month’s issue of BAR. The debris contained figurines, pottery fragments, pieces of ivory, and some clay seal impressions, known as bullae. These impressions were created when the owners of the seals stamped their seals into the soft clay and include the mark of King Hezekiah, previously reported here at The Daily Beast.

According to Mazar, “alongside the bullae of Hezekiah… [were] 22 additional bullae… among these is the bulla of “Yesha‘yah[u] Nvy[?],” which is most straightforwardly translated as “Isaiah the Prophet.” Given the importance of Isaiah to religious history, this seal impression is of great significance to Jews and Christians alike.

According to the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah was an eighth-century BCE prophet during the reign of King Hezekiah (one of the few “good kings” who ruled Judah before the Babylonian conquest. In the book of Kings, Hezekiah is described as second only to King David). Isaiah began prophesying during the reign of King Ussiah and appears to have lived through the reigns of Kings Jotham, Ahaz, and the first 14 years of the reign of Hezekiah. He is responsible, among other things, for the earliest biblical description of heaven, which he saw in a vision (Isaiah 6). Many scholars think that Isaiah’s vision of God enthroned in the heavens laid the groundwork for subsequent descriptions of heaven.

Isaiah is influential in Christian circles for his prophecies about the birth of the messiah and the necessity of the messiah’s suffering. Christians liked him so much that they composed the Ascension of Isaiah, an account of his ascent into heaven and martyrdom (by being sawed in half by a wooden saw, which sounds dreadful). The fourth-century Christian theologian Gregory of Nyssa wrote that the prophet Isaiah knew “the mystery of the religion of the Gospel” more perfectly than any of the other prophets. The biblical translator Jerome describes him as an “evangelist,” a term that implies that he is on a par with the authors of the Gospels, and the famous Christian orator John Chrysostom wrote that “the mouth indeed was Isaiah’s, but the oracle was wafted from above.” Andrew Davies, director of the Edward Cadbury Centre at Britain’s University of Birmingham, told The Daily Beast that “without Isaiah we’d be missing some of the most sorrowful but also the most hopeful of all religious poetry and some of the greatest theological innovation of all time.”

Even in his own day, Isaiah was important. Not only did he reside in Jerusalem and have a close relationship with the kings of Judah, but subsequent generations added to his words and work. The majority of scholars believe that the Book of Isaiah should be divided into two if not three sections, with each being attributed to a separate author. The author of the second segment, Second Isaiah (Isaiah 40-55), is thought to have written during the exile and predicted the return of the Jewish people from Babylon to Jerusalem. What the incorporation of these later sections in to the book shows is that Isaiah was important enough that others wanted to use his memory to spread their message.

Now, for the first time, we have an example of what might be his signature. Not only is this proof that Isaiah existed (not something scholars truly disputed), but, arguably, evidence of his role in eighth century BCE Jerusalem society. Not everyone who had a seal was of elevated high status (as they were a means of solidifying identity), but the Bible does describe Isaiah as a counselor of the king to whom the monarch would turn for advice. The discovery of his seal impressions in close proximity to that of King Hezekiah confirms the picture of a court prophet that we get from the Bible.

There are, as Mazar acknowledges in her article, some problems with the seal impression. Some of the letters that comprise the wording of the seal appear to have broken off. Additionally, most seals identify their owner with reference to their father “X, the son of Y.” On Mazar’s reading, the Isaiah seal doesn’t follow this format and instead identifies him by profession (i.e., prophet). Mazar weighs these options in her article and begins by considering all of the alternative explanations for the seal.

Robert Cargill, a professor at the University of Iowa, self-described skeptic, and the editor of BAR, told The Daily Beast that this was a “carefully written, responsible article” and that the magazine was careful not to claim definitively to have found the seal of Isaiah. “I appreciated Dr. Mazar’s methodical, responsible approach to this discovery, suggesting critical alternatives to the inscription rather than simply sensationalizing it.”

The discovery itself, Cargill noted, appears pristine: “There is no evidence to suggest that the scientifically excavated and provenanced material from the Ophel excavation was tampered with and/or mixed while it awaited wet-sifting.” He added that while he has personally spent much of his career debunking false archaeological claims, he thinks that Mazar has indeed discovered a seal impression of the prophet Isaiah and “the first archaeological and extra-biblical reference to the prophet.”

The ramifications of the discovery remain to be seen. Excavations in Jerusalem are inevitably politically charged because of the Israel/Palestine conflict. Mazar herself has been criticized in the past both for her involvement in excavations in Silwan (East Jerusalem) by Zionist organizations. The Ophel is, as Cargill noted, especially controversial “because of its proximity to the Temple Mount, and specifically to the al-Aqsa Mosque. In the past, any discovery speaking to a Jewish presence on the Temple Mount has been immediately seized upon by Israeli politicians for political purposes, touting it in support of their claims of the sovereignty of Jerusalem vis-à-vis the Palestinians. This, in turn, often leads the Palestinians to respond by claiming that any discovery is a fake, or by protesting the very presence of Israeli or Jewish archaeologists in what they understand to be Palestinian territories. Thus, excavating in Jerusalem, especially near the Temple Mount, is not for the faint of heart; it is intrinsically political, whether the archaeologist wants it to be or not.”

As politicized as all of this might be, the seal impression establishes in concrete terms something that scholars never really doubted in the first place: that a prophet named Isaiah served as adviser to King Hezekiah. What it is does not prove is the authenticity of his prophetic vocation, the accuracy of his predictions, or the truth of the Bible’s message.