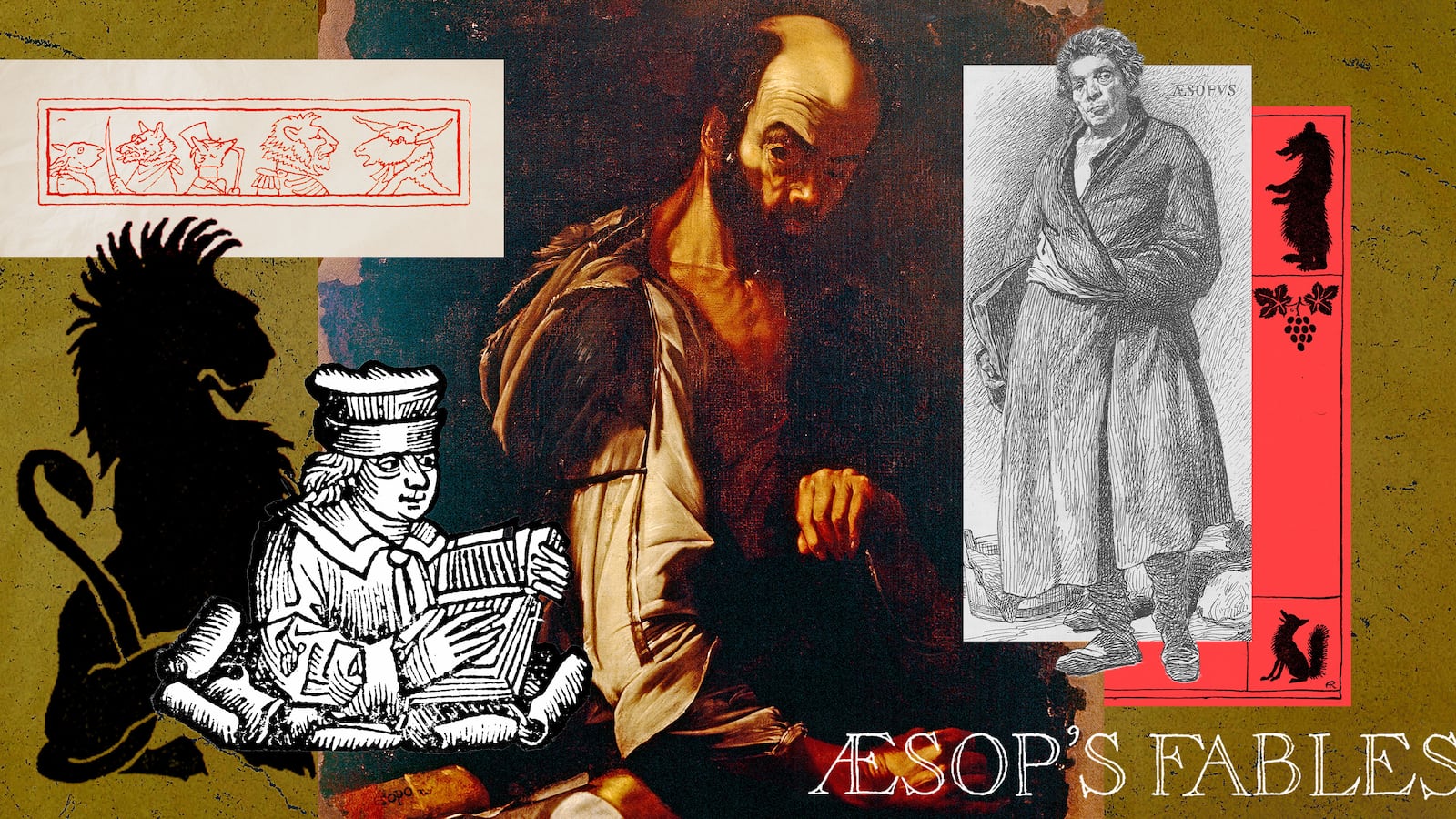

Chances are that at some point in your life you have run across Aesop’s Fables. Even if no one read you the Hare and the Tortoise as a child, a family member or teacher will have mentioned the Boy who Cried Wolf. These are child-rearing fan favorites that teach values like honesty and the rewards of hard work. Even if you somehow missed a moral education and skipped ahead to the world of finance some boardroom hawk will have mentioned the perils of ‘killing the Golden Goose.’ This saying also comes from Aesop and his morality tales. No ancient Greek figure has been as widely read and illustrated as Aesop, but the truth of the matter is that we don’t know if he even existed.

For a man whose stories have given shape to our childhoods, and those of hundreds of generations before us, he’s curiously hard to pin down. The earliest reference to him comes from the fifth century BCE historian Herodotus, who tells us that Aesop was a fabulist who lived roughly two hundred years beforehand. According to the Histories, Aesop was enslaved during his early years and was murdered by the people Delphi.

The list of ancient writers who know about Aesop and his fables is a veritable Who’s Who of ancient Greek intellectuals, but there’s little about Aesop that they can agree on. Aristotle says that Aesop was born in Mesembria, a Greek colony; the third century BCE poet Callimachus says that he was from Sardis; Maximus of Tyre called him the “sage of Lydia”; and a slew of ancient authors say he was born in Phrygia.

There’s a fictional Life of Aesop from the first century CE but it almost certainly represents traditions that grew up around the Aesop legend in the centuries that preceded it. This romance novel preserves many of the biographical details that appear scattered in other ancient sources. According to the oldest and longest version of the Life, our hero began his career as a hideous enslaved man who worked the fields and was unable to speak (Hideous is not an overstatement: one unsavory character likens him to a turnip with teeth and others compare him to garbage).

After assisting a lost priestess, however, Aesop receives the gift of speech from the Muses and becomes a “composer of fables.” He is purchased by the philosopher Xanthus and repeatedly outwits his new slaveholder by hilariously following his orders to the letter. In one instance, Xanthus asked Aesop to bring him an oil flask, which Aesop did without filling it with oil. On another occasion, when Xanthus instructed him to prepare a lentil pot for dinner, Aesop responded by cooking a single lentil.

This kind of pedanticism and blunt honesty usually doesn’t win you friends. Even after Aesop was manumitted and began to write fables his directness continued to offend. After insulting the inhabitants of Delphi, he was framed for temple theft. Despite his best storytelling efforts and attempt to claim sanctuary in a shrine dedicated to the Muses, he was forced off a cliff. Aesop had the last laugh, though, as the inhabitants of Delphi were punished three times over for their actions while Aesop achieved immortality through his fables.

As entertaining as it is, the Life of Aesop is less a source for the historical Aesop than it is a sign of the popularity that Aesop and his fables had achieved by the lifetime of Jesus. The “real” Aesop is nowhere to be found. Dr. Joseph Howley, an associate professor of classics at Columbia University and a scholar of Roman culture who studies enslavement and literature in the ancient world, told the Daily Beast that really “Aesop” is just the name we give to the imagined ‘author’ of a tradition of fables that emerged over a long period of time. This is a lot like (spoiler alert) the way the name “Homer” was applied to the imagined author of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

One of the most consistent things about Aesop’s biography is that he is identified as having been enslaved. This designation is connected to the character of his speech and use of the fable. Howley told me that Phaedrus, a Latin poet who rewrote many of the fables and was himself formerly enslaved, “explains that enslaved people cannot speak plainly, but must learn to speak obliquely in order to survive.” The fable, says Phaedrus, is something that only an enslaved person could devise. Thus, even though all kinds of elite people speak in fables, in the minds of ancient readers the fable was seen to represent what Oxford Professor Teresa Morgan has called “a kind of popular moral philosophy.” This kind of philosophy, Howley agreed, was “associated with enslaved, working, and otherwise disempowered or exploited parts of society.”

When the Life of Aesop took on literary shape in the first century CE collections of Aesopic fables were being re-written by people like Phaedrus and the Greek poet Babrius. The fables, like the Life, were in a state of interpretative flux. Writers like Phaedrus and Babrius saw themselves as participating in an unproblematic tradition of retelling that involved expansion and interpretation. The origin of these traditions was Aesop, but it was socially acceptable to re-tell those traditions.

As a mode of communicating, fables could serve a number of purposes, but they were generally seen as a fictitious and entertaining way to explain some aspect of life. The literati may have seen them as children’s tales for the uneducated, but even illustrious orators like Demosthenes had to recognize that people from all walks of life prefer to hear stories about donkeys to ponderous speeches. This doesn’t make them useless. Even animal tales can contain important ethical lessons and create what Morgan calls an “ethical landscape.” That’s why we teach them to our children, after all.

The landscape of the Aesop’s Fables, however, is a little vaguer about the traditional social virtues than we might think. Morgan notes that “friendship, trust, reliability, and honesty” are recommended, but only in a guarded manner. There’s a sort of pragmatic virtue at work here that emphasizes survival rather than principles. The world of the Aesopic corpus may not be as emancipatory or black and white as we might hope, but it is still a world in which the powerful are constrained by practicalities and the weak can survive through cleverness and co-operation. Neither Aesop nor Phaedrus’s fables are idealistic—their worlds are full of immovable hierarchies and threats of violence—but they do paint a picture of a world in which justice is omnipresent. Honesty may not always serve you well, and it certainly didn’t for Aesop himself, but you will always reap what you sow.

Whether we are talking about Aesop and his story or the fables themselves we are encountering a cultural mishmash of ideas and influences. The Life of Aesop follows the literary conventions of the ancient romance novel and borrows from other stories. The most popular version uses elements of the Sayings of Aḥiqar, an Aramaic text about a different fifth century BCE sage. Some of the Fables, too, seem to come from non-Greek sources. What this means is that both the man and the text are composite of a variety of cultures and traditions. “What fascinates me most about Aesop” said Howley “is that although the Greek tradition claims him and his fables, it always registers him as an outsider…The fact that some of his surviving fables appear in Akkadian, Egyptian, and other traditions leads me to think of Aesop as something of a fig leaf, a figure invented by the Greeks to mask their assimilation and co-opting of other, earlier traditions from West Asia and North Africa.”

When the printing press spread throughout Europe in the fifteenth century, Aesop’s Fables (and the story of his life) was one of the first works to be printed. The enduring popularity of “Aesop” means that he is constantly being told and retold: he has been read as an Ethiopian slave, a critic of industrial capitalism, a Japanese folklore teller, a Christian moralist, and an inspiration for Founding Fathers. Perhaps part of his appeal lies both in his status as an outsider and his malleability in the hands of his readers. Just as “Aesop” uses animals to speak about the realities of power, we use a mistreated outsider to talk about the human condition. There’s something alarming about that kind of appropriation, but there’s also something revealing and even Aesopic about it. In the long arc of the battle for cultural immortality, chickens come home to roost, the marginalized will have their say, and justice will out. And as we all know, slow and steady wins the race.