Today, remembering things—how to spell words, your partner’s cellphone number, birthdays and anniversaries—is fundamentally unnecessary. Who needs to remember details when all of human knowledge is available to you at the touch of a button? The cause of the recent decline of simply ‘knowing stuff’ is clear enough: blame the internet, blame smartphones, blame Google.

To those of us who grew up in pre-internet age we seem spoiled, but the truth is that we are all spoiled. Before the drawn of widespread literacy, information was transferred orally. People remembered lengthy stories, hours-long folktales, and songs and poems that were thousands of verses long. Scholars are in near-agreement that Homer’s Iliad began life as an orally performed poem. Ancient Celtic bards, too, are famous for their ability to recall thousands of stories and poems.

It’s easy to see why memory was so important to ancient peoples and that custodians of a community’s knowledge (religious leaders, elders, etc) would have elevated social status as a result. The question is, how did people do this? Are we just out of practice? How is it that ancient memories were so much better than our own?

Science writer Lynne Kelly studied the memory techniques of Aboriginal peoples, who commit vast amounts of information about plants and zoology to memory, in an effort to understand how this is done. In The Memory Code, the published version of her PhD dissertation, Kelly recalls how Aboriginal elders disclosed how it is that they remember so much information. According to Kelly they “encode” knowledge in song, dance, story and place.

The process by which people associate information with a specific place is known to historians and neurobiologists as the method of loci (or method of place). The first reference to this mnemonic practice is found in the writings of the Roman orator Cicero who attributed it to a poet Simonides of Ceos. Simonides narrowly escaped the collapse of a banquet hall and was able to identify the bodies of the dead based on his recollection of where guests had been seated during the dinner party that preceded the tragedy.

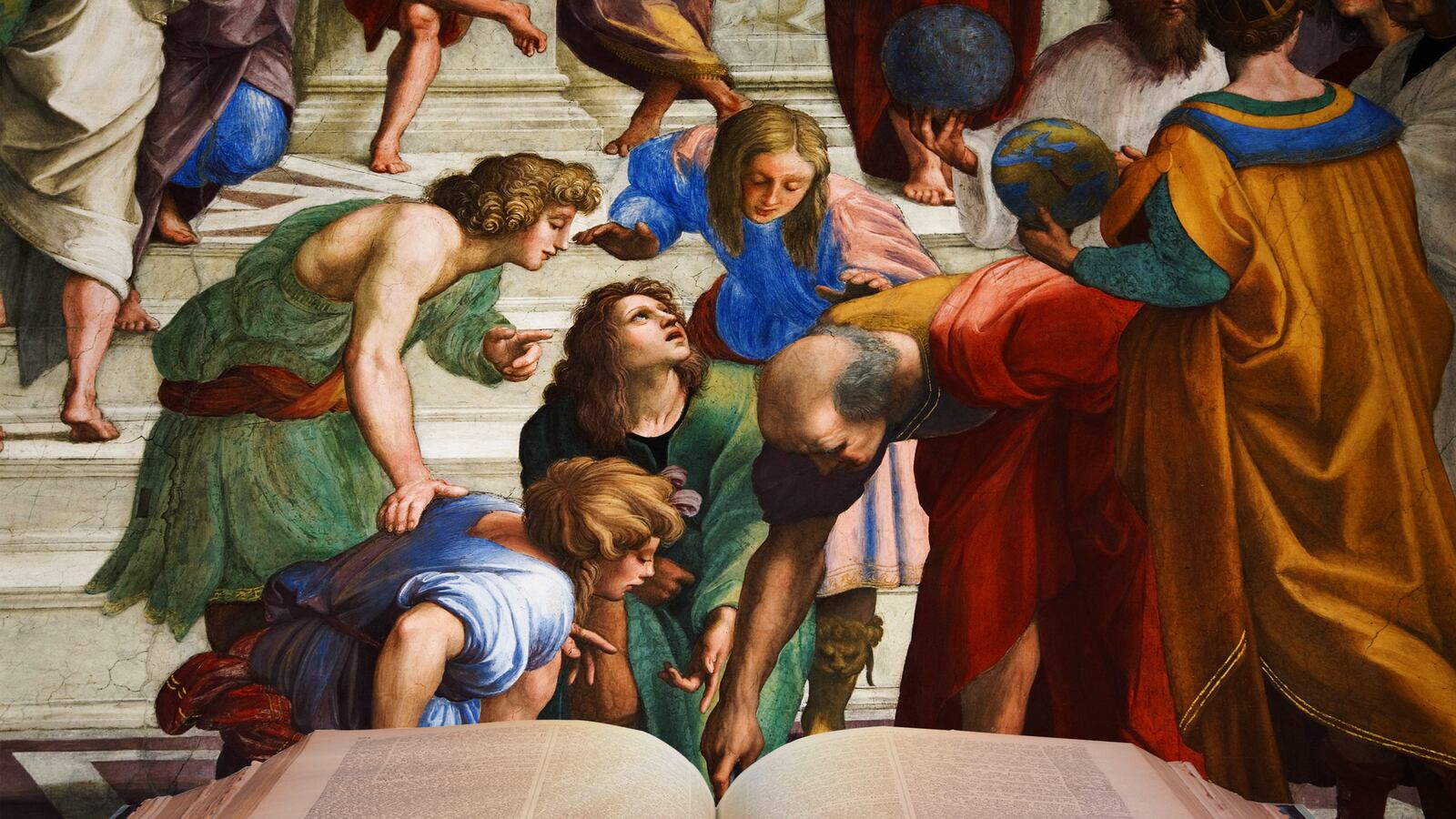

This method of associating a particular piece of information with the mental image of a location (the method of loci) is discussed at length by Aristotle. And features prominently in the writings of the Roman rhetorician Quintillian, because it allowed ancient orators and politicians to give speeches without notes. It was adapted by Christian monks and theologians and remained popular until the seventeenth century when phonetic mnemonic systems, like that of Stanislaus Mink von Wennssheim, came into vogue.

For Christians there’s a great deal at stake in the idea that ancient people had excellent memories. If they didn’t, how can we be sure that the Gospels accurately portray who Jesus was? After all, the Gospels weren’t written down for decades after the death of Jesus. In answering this question a number of scholars have turned to the study of memory and social memory theory in particular to explain the relationship between what actually happened and the events recorded in the New Testament. For example, biblical scholar Richard Bauckham, author of Jesus and the Eyewitnesses has argued that the memories of eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus impacted the subsequent tradition.

The problem is that theories of memory demonstrate that memory is always unreliable. It is possible, for example, to implant memories. Professors Chris Keith and Anthony Le Donne, contributors at The Jesus Blog, and specialists in social memory theory and the study of the New Testament told The Daily Beast that even if people had excellent memories in the ancient world, those memories would have been filtered through the thinking of subsequent generations.

In his book Jesus against the Scribal Elite Keith demonstrates that in the first century Christians remembered Jesus as both an illiterate person and a literate person. It is tempting, Keith told me, to try decide which of these two possibilities is true, at the outset and proceed only with that image of Jesus, but the more interesting question is why did Christians choose to think about Jesus in these ways? Any historical questions must come after asking that preliminary question. In other words, even individual memory does not escape the power of collective memory.

This shouldn’t bother us as much as it does. It might be shocking, LeDonne told me, to realize that your memory is only 85% effective. “That’s 15% of your life that you might be getting wrong. But it’s enough to keep living, keep loving the people close to you, keep acting like you can talk intelligently about Joan of Arc and Alexander the Great. It’s just about changing our default settings.”