Pay Dirt is a weekly foray into the pigpen of political funding. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox every Thursday.

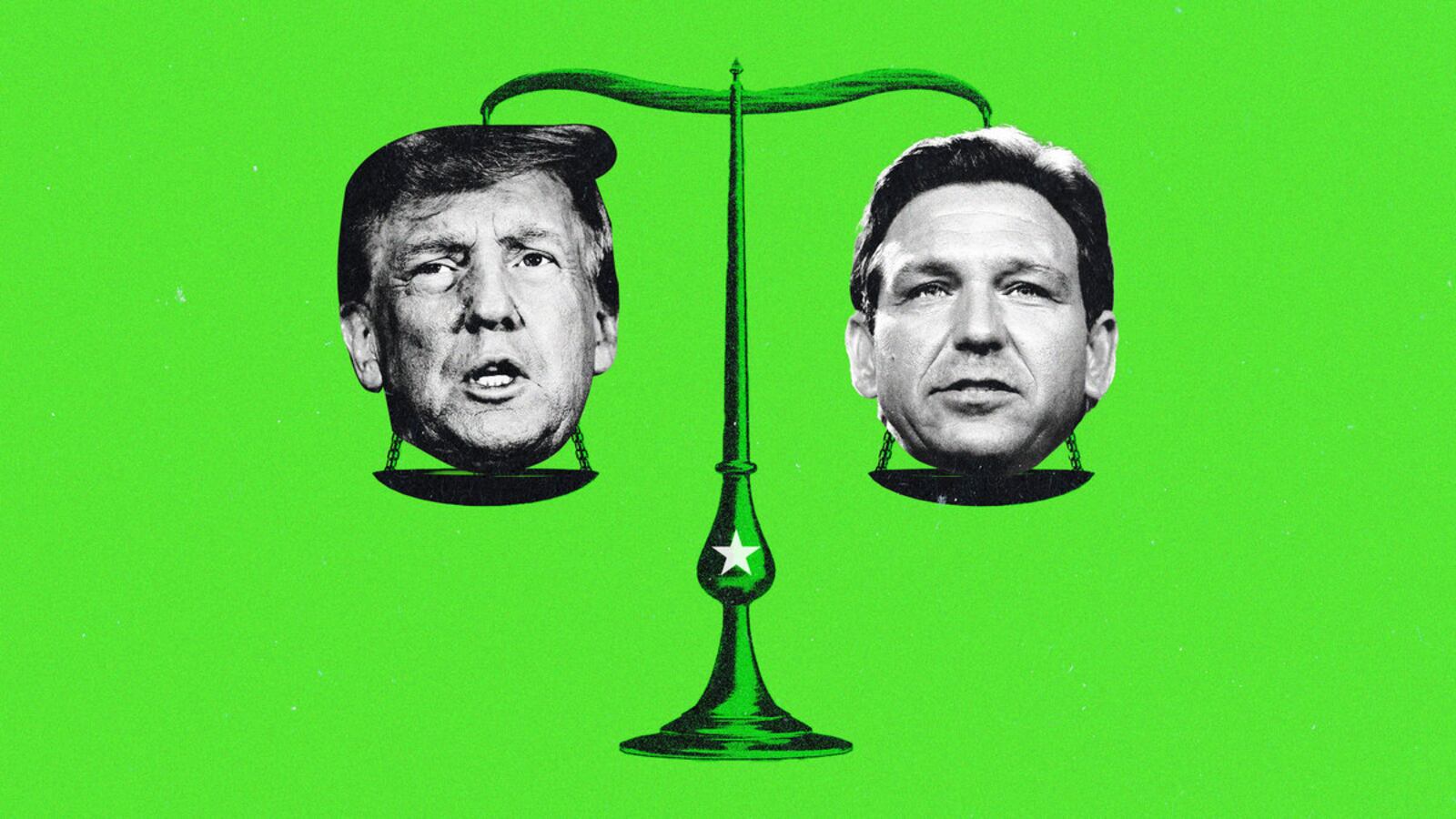

While the top two contenders in the nascent 2024 Republican presidential primary will at some point have to differentiate themselves for GOP voters, it doesn’t seem like campaign finance law is stacking up to be much of a battlesphere.

The campaigns of both former President Donald Trump and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis have pushed the bounds of federal fundraising laws in the early days of their bids. Legal experts say those moves—tens of millions of dollars worth of transactions in each case—may violate the law, give megadonors even more of an outsized influence, and undermine public faith in the democratic system.

Trump, of course, boasts a storied history of thumbing his nose at campaign finance regulations—and, according to legal analysts, repeatedly violating those laws. Of course, he didn’t let the fact that he’d left office deter him.

After departing the White House under the cloud of the Jan. 6 attack, Trump has continued to solicit money around false claims that the 2020 election was “rigged” and “stolen”—including several solicitations sent out in recent months. (A fundraising email from Dec. 28, 2022, said, “Donald J. Trump never thought, for even a moment, that the Presidential Election of 2020 was NOT Rigged or Stolen.”)

The Jan. 6 House select committee excoriated that tactic, and former federal prosecutors previously told The Daily Beast that dimensions of the Trump team’s 2020 efforts appeared to fit the definition of wire fraud. Those moves—including how the Trump operation spent that money—are now reportedly a focus of Special Counsel Jack Smith’s sprawling investigation into the events surrounding the attack on the Capitol. (Trump’s baseless election claims haven’t stopped him from raising money for a so-called “Ballot Harvesting Fund” ahead of 2024.)

More recently, however, both candidates have tested the limits of “testing the waters,” specifically the ban on so-called “soft money.” According to legal experts, Trump and DeSantis have flouted rules in order to bulwark their campaigns with astounding piles of cash—tens of millions of dollars in both cases.

Erin Chlopak, senior director of campaign finance at bipartisan watchdog Campaign Legal Center, explained the soft money ban.

“It’s fairly simple: Federal law prevents federal candidates and associated entities from soliciting, receiving, directing, transferring, or spending soft money—funds that are not subject to federal campaign finance rules,” Chlopak told The Daily Beast.

These rules, she said, are in place to “ensure that our system is transparent and as free from corruption as possible.” They include disclosure requirements, restrictions on who can donate, and, importantly, individual contribution limits. (In 2024, donors can give no more than $3,300 to a candidate per election.)

But according to Chlopak, there’s a specific rule where both Trump and DeSantis appear to have crossed a legal line—the “testing the waters” period.

Under the law, someone becomes a candidate for federal office when they raise or spend more than $5,000 in support of their candidacy. But the law also allows for a “testing the waters” grace period, where potential candidates can engage in financial transactions without triggering federal reporting requirements even if the amounts exceed the $5,000 threshold.

“It’s a timing issue,” Chlopak explained. “Campaign finance rules apply to someone who’s a candidate, and sometimes there are questions about what point that happens. But you can’t just say you haven’t quite made up your mind and use that as an excuse to raise or spend millions of dollars.”

When a candidate decides to run and exits the testing-the-waters phase, the laws kick in retroactively, requiring them to disclose their prior activity. The FEC makes it clear that “all funds raised and spent during the testing the waters period must comply” with rules governing contribution limits and other prohibitions—such as accepting corporate money. (Failed GOP Senate contender Mehmet Oz retroactively disclosed spending millions of dollars of his own money ahead of his announcement.)

Trump and DeSantis, Chlopak said, abused the testing-the-waters period to stash massive amounts of money while engaging in what would otherwise be prohibited transactions. Specifically, they used the window before they officially declared their bids to raise giant sums of money directly into super PACs supporting them—something candidates aren’t allowed to do, since super PACs have much looser restrictions than campaigns and can raise unlimited amounts of money from individuals and corporations.

The Trump operation did this through his “Save America” leadership PAC, transferring $20 million to the “MAGA Inc.” super PAC in the weeks before he officially declared his 2024 candidacy. More recently DeSantis tried the same move with his state-level PAC, which this spring transferred more $80 million into the “Never Back Down” super PAC dedicated to supporting his run. That same super PAC is also reportedly routing $500,000 back to the DeSantis campaign.

After The Daily Beast reported on Trump’s scheme last October, CLC filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission alleging that the transfers were illegal. But the Trump operation plowed ahead, and CLC amended that complaint in May to account for more transfers—a standing total of $60 million.

Then, on Tuesday, CLC filed a similar complaint targeting DeSantis, alleging that his PAC broke the same law.

“When somebody running for federal office—particularly the highest office—is raising and spending massive amounts of money without complying with the law, that can really undermine faith in our already fragile political system,” Chlopak said.

The DeSantis team also appears to have pushed the limits of ethics rules governing who can raise campaign money, enlisting administration officials to reportedly pressure lobbyists for donations.

Jordan Libowitz, communications director for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, told The Daily Beast that those solicitations amount to “pretty much blackmail.”

“He’s using the power of the governor’s office to advance his political career,” Libowitz said. “That’s pretty much blackmail, and it could trigger some laws if these aides were doing it from their office or while on the clock. But even if it’s on their own time, it puts donors in a very awkward position, suggesting that if you don’t give us money then there will be repercussions and we can take action on that.”

Norman Ornstein, emeritus scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a center-right think tank, called DeSantis’ fundraising “blatantly illegal.”

“Super PACs are supposed to be completely independent of campaigns,” Ornstein told The Daily Beast. “No matter how the money was raised—in this case, following individual contribution limits—this is the antithesis of independent. It is an in-your-face flouting of both intent and letter of the law.”

But Ornstein, a registered Democrat, expressed little hope for accountability.

“Given that the Federal Election Commission has a set of Republican commissioners whose mission is to keep from enforcing campaign finance laws, they might well get away with it,” he said.

Brendan Fischer, a campaign finance law specialist and deputy executive director of Documented, agreed with this view, telling The Daily Beast that the candidates appear to be exploiting the law as well as the regulators charged with enforcing it, but whose lackluster efforts have “promoted a culture of near-impunity.”

“Both DeSantis and Trump know that they can aggressively push the legal envelope and expect to get away with it,” Fischer said.

But Fischer also noted that since the Supreme Court’s landmark Citizens United decision that gave rise to super PACs, candidates in every presidential cycle have worked to create or expand loopholes.

He pointed to the $100 million that 2016 presidential hopeful Jeb Bush raised into a super PAC “while pretending he wasn’t a candidate,” and Hilary Clinton’s claim that she could coordinate with a nominally “independent” super PAC since it wasn’t buying ads. And Trump has consistently chipped away at regulations, claiming that a loophole allowed his campaign to hide the recipients of nearly $800 million in expenses.

“As a result, super PACs are now a central feature of the campaign landscape, and megadonors and special interests have an incredible amount of power and influence,” Fischer said.

But the watchdogs have a strange bedfellow on this issue: the Trump team.

In March, Trump’s operation—which has famously survived dozens of FEC complaints detailing what appear to be clear violations—filed a state-level ethics complaint against DeSantis in Florida. Among the allegations? Violating the state’s own version of the testing the waters period.

But the irony doesn’t end there. That complaint was filed by the MAGA Inc. super PAC, the same entity Trump gave millions of dollars just ahead of his own announcement. And, it turned out, the Trump team got a taste of its own medicine in May, when the Florida Ethics Commission scrapped the complaint.

In the decision, the commission—a majority of its members appointed by DeSantis—cited a “lack of legal sufficiency.”