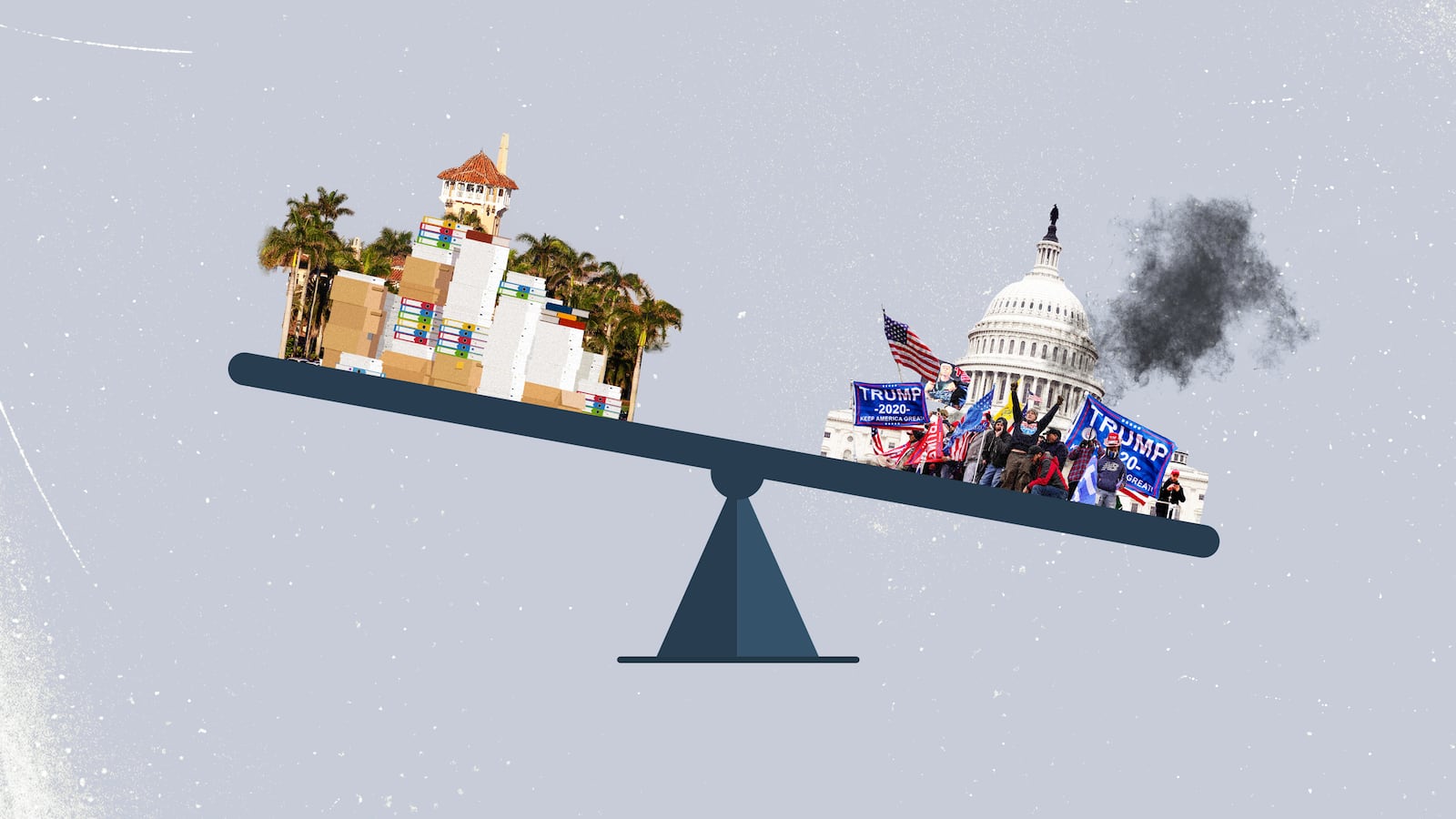

In the never-ending saga of Trumpworld scandals, the execution of a search warrant by the FBI at Mar-a-Lago has understandably dominated headlines in recent weeks. The story is bizarre, even by Trump standards.

While there’s plenty we don’t know, what’s apparent is that Trump stashed hundreds of highly classified documents and other presidential records at his personal residence/private club in Palm Beach, Florida, and that the Department of Justice is pursuing a criminal investigation of the matter. It also seems as though Trump has been caught red-handed in violating a number of criminal statutes.

The temptation is, therefore, strong to proclaim that surely, this time, finally, we got him.

But no matter what we find out about Trump’s motives and actions for hoarding state secrets, some perspective is in order. Pretty much nothing we’re likely to find out could be worse than what Trump already did with regards to the 2020 election—up to and including Jan. 6.

Even the most extreme (and unlikely) hypotheticals for what Trump was up to with these documents—like outright selling nuclear secrets to a foreign power—would still be a lesser offense than a defeated President of the United States trying to install himself as an unelected autocrat and siccing a mob on Congress towards that end.

The Depravity of Normalization

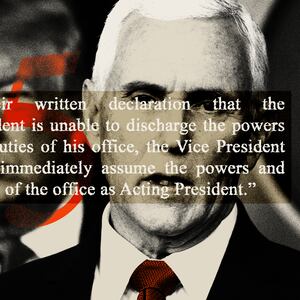

From November 2020 to January 2021, the United States experienced a constitutional crisis, not in the sense of simply an acute political confrontation, but a constitutional crisis in the technical sense: a live dispute and uncertainty over the constitutional structure of the government.

We can debate over whether to call it an attempted coup (it was, albeit a very poorly attempted one), but such semantics should not detract from the unprecedented gravity of the situation and the magnitude of Trump’s political crime. In the history of the republic, no incumbent president has ever refused to accept defeat for re-election, obstructed the electoral process, and tried to cling to power by extra-legal means.

Even before the first rioters breached the Capitol, the office and powers of the presidency had been turned towards an attempt to overthrow the Constitution itself. Not that presidents haven’t violated the Constitution in many ways before, of course. But nobody, until Trump, tried to destroy the very processes at its core.

Pro-Trump supporters storm the U.S. Capitol following a rally with President Donald Trump on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington, D.C.

Samuel Corum/GettyAt the end of the day, the system held. The constitutional architecture survived the stress test. Congress reconvened, certified the results, and Joe Biden took office without any further disruption or violence. The rest of the government outside of the West Wing—including most of those holding office within his own administration—refused to go along with the farcical autogolpe.

But since then, Trump continues to be the de facto party leader and prohibitive frontrunner for the 2024 nomination. So how well did the system actually hold?

There Are Crimes, and Then There Are High Crimes

The Jan. 6 Committee hearings have offered, to good effect, a stark reminder of how depraved and reckless Trump’s actions were—and how complicit he was in inciting violence. But the hearings did not focus much on what could have been, had Trump not effectively backed down after the sacking of the Capitol.

If Trump’s plan had succeeded, meaning if he retained any real operational control over any substantial parts of the government after noon on Jan. 20, then the events of Jan. 6 would have paled in comparison. And while many more things would have had to go catastrophically wrong for that to have happened, that it was the goal of the most powerful man on the planet is still a staggering betrayal.

Presidents of the United States do not swear to obey rules regarding the classification and archiving of documents, or even to serve the best interests of the American people. They swear to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” That the oath was phrased in that manner was no accident or mere formality. It is the most important and fundamental obligation of the office. And no president has betrayed it so directly and shamelessly as Trump did in attempting to create a government entirely outside of the Constitution and its legitimacy as the supreme law of the land.

Local law enforcement officers are seen in front of the home of former President Donald Trump at Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, on Aug. 9, 2022.

Giorgio Vier/AFP via GettyUnfortunately, the scope and magnitude makes it difficult, though not impossible, to address through criminal law. This is precisely why the intended mechanism to protect the republic from such bad actors is impeachment and disqualification. As Alexander Hamilton noted in Federalist No. 66, the offenses covered by impeachment “are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

Something like stealing government documents or mishandling classified secrets, on the other hand, is the kind of matter criminal law addresses all the time. Whether other charges related to the election are ultimately brought against Trump or not, it’s no surprise that this sort of venal but relatively cut-and-dry offense has attracted quicker public action from the Department of Justice.

This does not mean, however, that Trump has finally done something bad enough to merit criminal sanctions. Because the 2020 election crisis unfolded in public at the time, and the basic facts of it have been known, there is a danger of it fading into a background assumption of American politics.

Treating the hoarding of old Presidential Daily Briefs at Mar-a-Lago as potentially worse or more serious than attempted overthrow of the American system of government is a mistake.

There is also a temptation to view this as akin to nailing Al Capone for tax evasion, a comparison that has been frequently mentioned. Sure, he obviously did worse things, but any conviction will do. There are good civil libertarian reasons to doubt that we should actually remember the Capone example that fondly, or want it repeated in that way under very different circumstances. But either way, if something like that is what happens, it should be remembered like Capone in one respect: as incidental to the real reasons for his notoriety and infamy.

The depravity of Trump’s ongoing presence and influence in American politics is not that the smoking gun has yet to be revealed, or that people don’t yet know how bad he is. There is no new scandal that will break the spell, finally discredit him, and return American politics to something more like normalcy. Even the possibility of criminal indictment and conviction does not remove him from the stage as a potential presidential candidate. We must grapple with a deeper problem: people have already seen Trump at his worst, in the act of committing the most serious crime a president can commit. And for too many, they simply don’t see it as a problem.

Former President Donald Trump is displayed on a screen during a hearing by the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol on June 9, 2022 in Washington, D.C.

Drew Angerer/GettyTrump offers a target-rich environment for his political opponents. His erratic behavior, unpopular policies, and scandal-plagued single term offer much to criticize. But the primacy of what he did in the final months in office is not merely a question of political tactics. It is what sets him apart as a unique threat, outside the bounds of normal politics. And it is the lesson we need to imprint on American history, to deter any future attempts at the same crime.

We’ve had corrupt presidents before, we’ve had criminal presidents before, and we’ve had presidents who mishandled classified information. But we’ve only had one president who tried to steal the presidency itself.