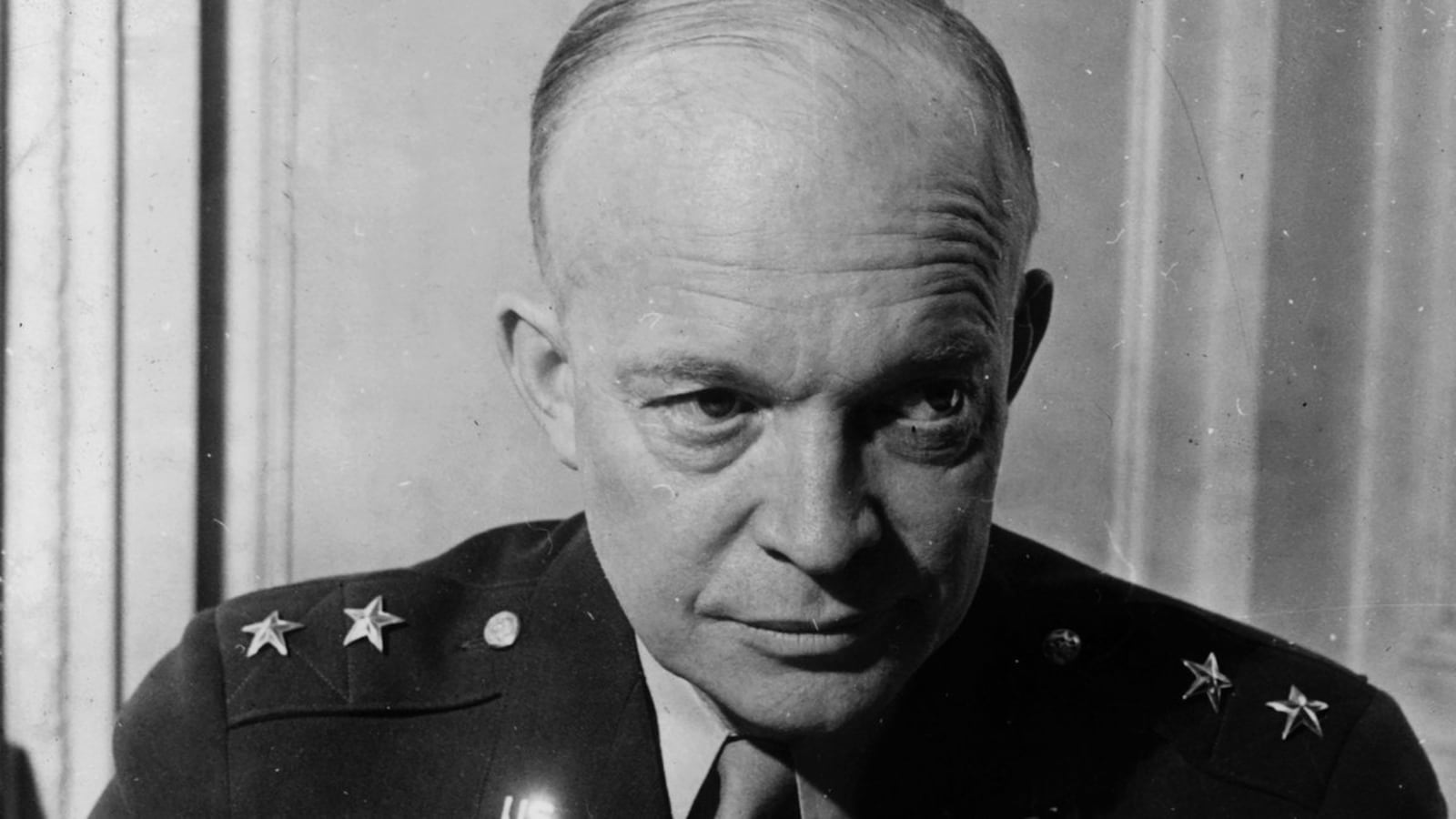

When in 1948 General Dwight Eisenhower, freshly retired from the Army, published Crusade in Europe, his memoir of his leadership of the Allied forces in Europe in World War II, he could count on a vast American audience hungry for details about a war they had experienced either as combatants or civilians on the home front. Eisenhower had a natural bestseller on his hands.

The new paperback edition of Crusade in Europe that Vintage has just re-issued won’t generate 1948-level sales. But those reading Crusade in Europe for the first time will be fascinated with what they find.

Eisenhower offers more than a clear account of how America and the Allies achieved victory in Europe over Germany. He provides perspective on how America can function today as a global power without getting sucked into unwinnable wars.

For Eisenhower, the chance to write Crusade in Europe was, as his biographer Michael Korda has pointed out, an opportunity to earn the kind of money he could never make as a career officer. After capital gains, Eisenhower was left with nearly $500,000 from Crusade in Europe, a sum equal to over $5 million today. Doubleday, his publisher, did equally well. Crusade in Europe sold over a million copies in the United States and was published in 22 foreign-language editions.

Eisenhower did not churn out a slapdash memoir, nor did he use Crusade in Europe as a vehicle for settling scores with military rivals. He took advantage of the files and diaries that he had kept over the years, and he prepared himself for writing by rereading Ulysses Grant’s Personal Memoirs, which he admired for “their lack of pretension.” The result was a memoir that not only sold well but earned praise for its prose. As Drew Middleton, The New York Times war correspondent in Europe from 1939 to V-E Day, noted in his 1948 review of Crusade in Europe, it has a clarity that “raises the book to the first rank of war memoirs.”

Eisenhower’s title for his memoir comes from the message he sent on the eve of D-Day: “Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force: You are about to embark upon a great crusade toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty loving people everywhere march with you.”

Crusade in Europe revolves around the decisions Eisenhower made in order to conclude the war with Germany as swiftly as possible while keeping civilian and military losses as low as possible. It was a difficult balancing act. Eisenhower not only had to deal with a seasoned German army that had been fighting years before America entered the war. He also had to deal with difficult generals on his own side. There was no avoiding confrontations with Britain’s Bernard Montgomery, who thought he should be ground commander of the Allied forces, or with George Patton, Eisenhower’s fellow West Pointer, who in the midst of the war created a scandal by slapping a shell-shocked soldier who he thought was guilty of cowardice.

In Crusade in Europe, Eisenhower plays down as a “splendid joke” President Harry Truman’s offer to help him if he wanted to pursue the presidency in 1948, but what makes Crusade in Europe so engaging now is the way it looks into the future. Eisenhower had no doubt that America and Russia would be bitter rivals after the war. “The compelling necessities of the moment leave us no alternative,” he wrote of America’s relations with the Soviet Union, “in terms of adequate military preparedness.”

At the same time, Eisenhower was willing to acknowledge the limits of American military power. In Crusade in Europe, he talks about the fact that during the war American troops never reached Berlin in time to establish control of the city before the Russians got there, as many hoped they would. Eisenhower has an unapologetic explanation for why he never pursued this objective. He notes that when American forces might have made a move on Berlin, they were still on the Rhine, hundreds of miles from Berlin, while the Russians were firmly established on the Oder River just 30 miles outside the city.

Had America tried to beat the Russians to Berlin, two things would have happened, Eisenhower argues. The Russians would have reached the city before America got there, and American divisions not driving toward Berlin would have been immobilized by a lack of supplies. “This I felt to be more than unwise; it was stupid,” Eisenhower writes of the idea that he should have moved heaven and earth to beat the Russians to Berlin.

Crusade in Europe makes clear that for Eisenhower such restraint was the better part of valor. In the conclusion of his account, it is not his military triumphs that Eisenhower chooses to emphasize but his belief that “rigid concepts of national sovereignty” no longer make sense.

Reading Crusade in Europe nearly 75 years after it was written reminds us that as president Eisenhower ended the Korean War, refused to send American troops to Indochina to help the French with their colonial war, and declined to join Britain and France in seizing control of the Suez Canal in 1956. Eisenhower’s idea of containing the Soviet Union, much like that of George Kennan in his famous 1947 essay “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” included pursuing the cold war on a variety of fronts but stopping short of getting America trapped into conflicts that went nowhere. The kinds of interventions that in recent years have bogged down American troops in Afghanistan and Iraq are exactly the kinds of interventions Eisenhower knew to avoid.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of literature and American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America’s Coming of Age as a Superpower.