The bipartisan group No Labels is well on the way towards its goal of raising $70 million to advance its notion of a “unity ticket” pairing a Republican and a Democrat. The effort is a “mirage” or a “sure spoiler”, pick your label. Former vice-presidential candidate Joe Lieberman, a disgruntled Democrat who backed John McCain over Barack Obama, co-chairs the group.

He calls the effort an insurance policy, and says they don’t want to be “Ralph Nader on steroids.” But as fundraising continues, spearheaded by No Labels founder Nancy Jacobson, the centrist Democratic group Third Way is sounding the alarm, pointing out what should be obvious: that a third-party candidate in 2024 would help Donald Trump (or someone like him) and hurt President Biden.

In the event a “unity” candidate wins enough electoral votes to keep anyone from reaching 270 electoral college votes, the number needed for victory, the Republican House would decide the winner, and clearly it wouldn’t be Biden.

ADVERTISEMENT

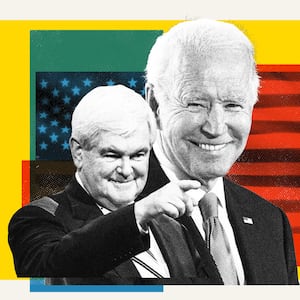

No Labels founder Nancy Jacobson, group‘s co-chair former vice-presidential candidate Joe Lieberman.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty“I do believe Trump will be the nominee, and if not Trump, someone who is Trump-like,” says Jim Kessler with Third Way. “It’s time to pay attention to a potential third-party candidate run in 2024, because it’s getting real, and it could be a huge problem. They’re pushing it like it’s a neutral effort, but Larry Hogan or Liz Cheney or Kyrsten Sinema–they appeal to suburban voters, and that’s the Democrats’ new base. That’s who we’re winning.”

The third-party ploy feeds a Democratic fantasy of backing Liz Cheney for the White House because of her role on the Jan. 6 committee, but any Democrat who spent five minutes perusing Cheney’s policy positions, would back off. She’s anti-choice for starters. And former Maryland governor and moderate Republican Larry Hogan is not going to win over MAGA Republicans, notes Kessler. “He’ll win over the Republicans who read the Wall Street Journal and went with Biden this time.”

A new wrinkle for 2024 is Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema’s decision to leave the Democratic Party and become an Independent. “If you’re raising $70 million to put a candidate on the ballot in all 50 states, I’d imagine you’d reach out to her,” says Kessler.

Sinema saw the writing on the wall—that progressives are readying a challenge and she would be unlikely to prevail in a Democratic primary in 2024. Psyching out the famously elusive Sinema is useless, and her new status as an Independent only adds to her mystique.

It’s too early to float names, says Ryan Clancy, chief strategist for No Labels. The group is in the field now with Stagwell polling the public, and they will introduce a policy agenda in the new year. They’re also building a voter file to rival the database of the two major parties. Stagwell’s CEO is Mark Penn, a former Clinton pollster who is married to the No Labels founder Jacobson.

Kyrsten Sinema, Larry Hogan, and Liz Cheney.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/GettyAdvocates of No Labels insist it is a good-faith effort that got underway well before the midterms, when the Republicans looked like they had built a red wave and Joe Biden looked like he and his party were headed to the ash heap of history. “The midterms were a surprise to many people, and it may well be the case that this isn’t needed,” Clancy told The Daily Beast.

However, putting the brakes on the effort is unlikely. A Unity convention is set for April 2024. “There’s a lot of optionality built into what we’re doing,” Clancy continued. “Every step along the way, we have an off-ramp. If at any moment, the assumptions we made a year ago are no longer true, the economy is better, and the public is less cranky–and there’s no other candidate who is capturing the public’s imagination–then we’ll pull the plug.”

That’s a lot of “ifs,” but Clancy has another one, “If we wait until the spring of 2024, and the public is desperate for an alternative and no one’s done the groundwork, it’s too late.”

At a virtual briefing last week held by No Labels for its supporters, guest analyst Jeff Greenfield was asked his opinion of a so-called unity or fusion ticket. He reminded No Labels co-chair Joe Lieberman that Green Party candidate Ralph Nader helped elect George W. Bush president. Nader supporters broke 2 to 1 for the Democratic ticket headed by Al Gore in Florida in 2000.

Without Nader on the ballot, Gore/Lieberman would have won the state, and the presidency. “I’m very skeptical about an alternative campaign,” said Greenfield. “A group like No Labels should keep its powder dry.”

“We don’t want to elect a candidate for president that we didn’t want to elect,” Lieberman replied. “We don’t want to be Ralph Nader on steroids.”

Lieberman and others have taken to calling the unity ticket a “2024 insurance policy,” but they are launching a major project to build a voter base and these are professionals, says Kessler. “They’re knowledgeable—they’ve been on presidential campaigns in the past—and no one’s paying attention,” he says.

“Politics is like theater,” he continues, invoking Anton Chekhov’s rule of playwriting. “If you show a gun in the first act, you’d better use it by the third act. They’re going to convince enough people that this is a real opportunity.”

Polls show that a sizeable portion of the American electorate is disillusioned with a possible Trump/Biden matchup. But third party candidates generally poll higher than where they end up, and the number of electoral votes garnered by third parties from 1900 on, taken together, don’t add up to the 270 needed to win the presidency. John Anderson in 1980 polled at 26 percent, and got 7 percent of the vote; Ross Perot reached a high of 36 percent in the polls in 1992, at one point out-distancing both George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. He ended up with 18 percent of the vote on election day, and not a single electoral vote.

Despite the disclaimers offered by Lieberman and others, No Labels is unlikely to dismantle its effort and shift its focus to the Congress, where it backs members who work across the aisle and helped create the Problem Solvers Caucus. So far, only Third Way has raised questions with a report that calls a unity ticket a “mirage.”

Asked why they’re sounding the alarm now, Kessler says, “Because it could be so dangerous and our democracy is hanging on by a thread, we don’t need somebody splitting the anti-Trump voters out there. We’re centrist Democrats–we’re Biden supporters–this has nothing to do with us vs No Labels. We’ve worked with them in the past, and probably will again. This is not the time to mount a third-party effort.”

Until now, this effort has gone largely unnoticed, but given the money and the players involved, and the inevitable longing for the idyllic alternative, it won’t stay hidden for long. “Be a part of history” is the No Labels’ sales pitch—a pledge it is positioned to fulfill for good or ill.