Lear deBessonet, the artistic director of Encores, says the season’s “specialty has been unearthing lesser-known gems from the Broadway canon,” and staging them at New York’s City Center. Well, there is nothing “lesser-known” about Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods, but really, so what, because this is a supremely gorgeous presentation (until May 15), and the best tribute imaginable to the master himself, who died aged 91 last November.

The show, packed with stars clearly having the times of their lives, is both extremely funny and also profoundly moving, switching between both in a blink at certain moments, while in the second act letting its emotional power grow and coalesce until you should, if you have a functioning heart, be in snuffling streams of tears. It is beautifully sung, witty, the orchestration lush and precise—and even for a relatively bare-staged presentation of songs still feels like a substantial production.

This Into the Woods crystallizes the show’s bigger messages too. We really see why going “into the woods” is both terrifying and liberating to this gallery of familiar fairytale characters; why true bravery can be experienced in the strangest ways; what love means; what justice can look like; how community should behave; what grief is; and what “family” means. All of this is somehow lightly and deeply scored into text and lyrics, straight to our ears, hearts, and minds.

The repeated incantation “Children will listen” sounds like a lullaby and also—for this critic, considering the onslaught of anti-LGBTQ and other bigotries in this moment—also a furious caution to those stoking the fires of prejudice and social and cultural restriction. (Not that they would ever listen, but still.)

Neil Patrick Harris plays the Baker and Sara Bareilles his wife, desperate to have a baby and set an impossible set of tasks by the Witch (Heather Headley) in order to have their wish granted. Headley begins the show hunched and threatening, a cloud of grey curls obscuring her face, and then, ta-da, just wait for her glamorous transformation and her powerhouse renditions of “Stay With Me,” “Witch’s Lament,” and finally “Last Midnight.”

l to r: Julia Lester and Denée Benton in "Into the Woods."

Joan MarcusAgainst her, or indeed anyone, Harris is a furrow-browed squirrel in headlights, and then a hero despite himself. He has a lovely comic and moving chemistry with Bareilles, who refuses to stay home and wait for him to collect all of the Witch’s demands from the woods.

Her final song, “Moments in the Woods,” a meditation on what her life is, what possibilities there could be, and what is ultimately real and important, will make you appreciate the genius of Sondheim’s lyrics—so marvelously open to the strangeness of human hearts and motivations—while also a testament to performers like Bareilles who possess the formidable interpretive skills of making sense of them. Turns out there is a choice between getting kissed by princes and your baker husband.

The production laughs at itself and its absurdities when it needs to, and also takes itself absolutely seriously. Denée Benton is a shimmering, canny Cinderella, also faced with a prince-related decision to make. Julia Lester makes an astonishing New York theatre debut as Little Red Ridinghood, rolling her eyes and not buying anything anyone is saying, and taking the air and mystery out of anything crazy happening around her. Cole Thompson is a sweetly off-kilter Jack, frustrated at having to face the giant, when really he just wants to be reunited with Milky White, his cow, operated as a puppet by Kennedy Kanagawa with such impressive dexterity that we follow his every movement and expression.

l to r: Ann Harada, Cole Thompson, Kennedy Kanagawa in "Into the Woods."

Joan MarcusThe excellent Ann Harada is Jack’s long-suffering mother, despairing of his innocence and then just movingly despairing. Gavin Creel plays both the wolf foolish enough to torment Little Red Ridinghood, and then Cinderella’s prince, who is a catch and isn’t a catch, and despite the leaping flourish he appears with—just like Rapunzel’s prince (Jordan Donica)—is sadly lacking. (And he knows it, as Creel wittily shows.) David Patrick Kelly is our narrator and a mysterious man, eventually drawn against his will from his safe perch of apparent omniscience.

After the various fairytales are resolved at the end of act one, Sondheim takes the audience beyond the traditional happy-ending fruition of the stories in act two, with more laughter and even more tears as everyone heads back into the woods, to face a none-too-happy giant. Here, all the show’s larger messages around revenge, justice, and love come into sharper focus. Some things seem untenable, others impossible to come back from. Again, Sondheim and this company don’t wrench things into a happy ending, but it is an ending that points to futures being shaped from tragedy by determination, wit, circumstance, a belief in mutual care and responsibility, and sheer force of will.

The woods are transformative for all the characters—a testing, changing challenge. Another Sondheim lyric popped into this critic’s mind at the end. “There’s a place for us,” Tony and Maria sang in West Side Story, and so it is the characters here end up, tentatively making their way finally out of the woods to find some kind of place together somewhere.

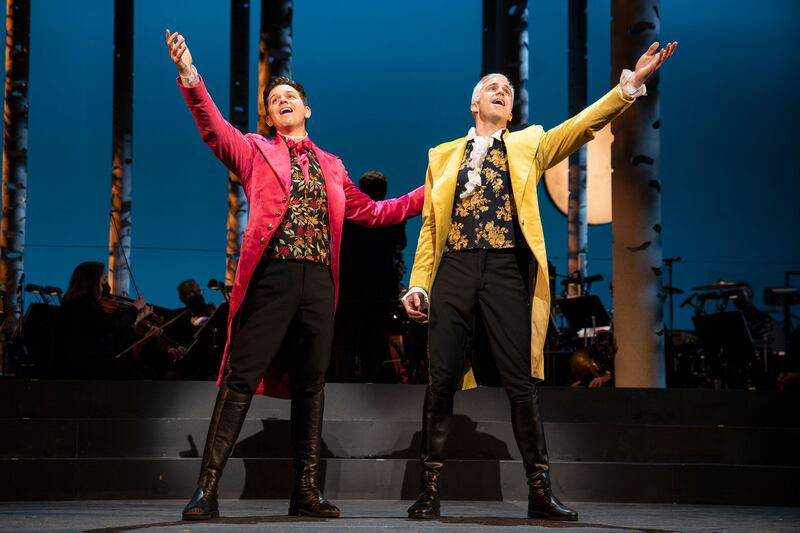

l to r: Jason Forbach and Gavin Creel in "Into the Woods."

Joan Marcus