The mysterious group found its way to Austin D. while he was working a dead-end job at a Pittsburgh Starbucks.

“I was feeling a little depressed and hopeless,” Austin told The Daily Beast. “I’d got out of undergrad with a lot of debt. I felt like the opportunities that I’d been taught were available, were not really available. I was still working the same minimum-wage job. My headspace was primed for someone who appeared to have all the answers.”

Then someone with answers appeared. While discussing the exploitation of Starbucks workers, a fellow barista recommended Austin join a group to study the writings of former Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong.

Austin’s first reaction was skepticism. “I was like, didn’t that guy murder a bunch of people?”

The coworker assured Austin that he was incorrect. (Up to 45 million people are believed to have died, most of starvation, under Mao’s Great Leap Forward plan.) It was the beginning of Austin’s years-long involvement in an organization that he and other former members now describe as a cult.

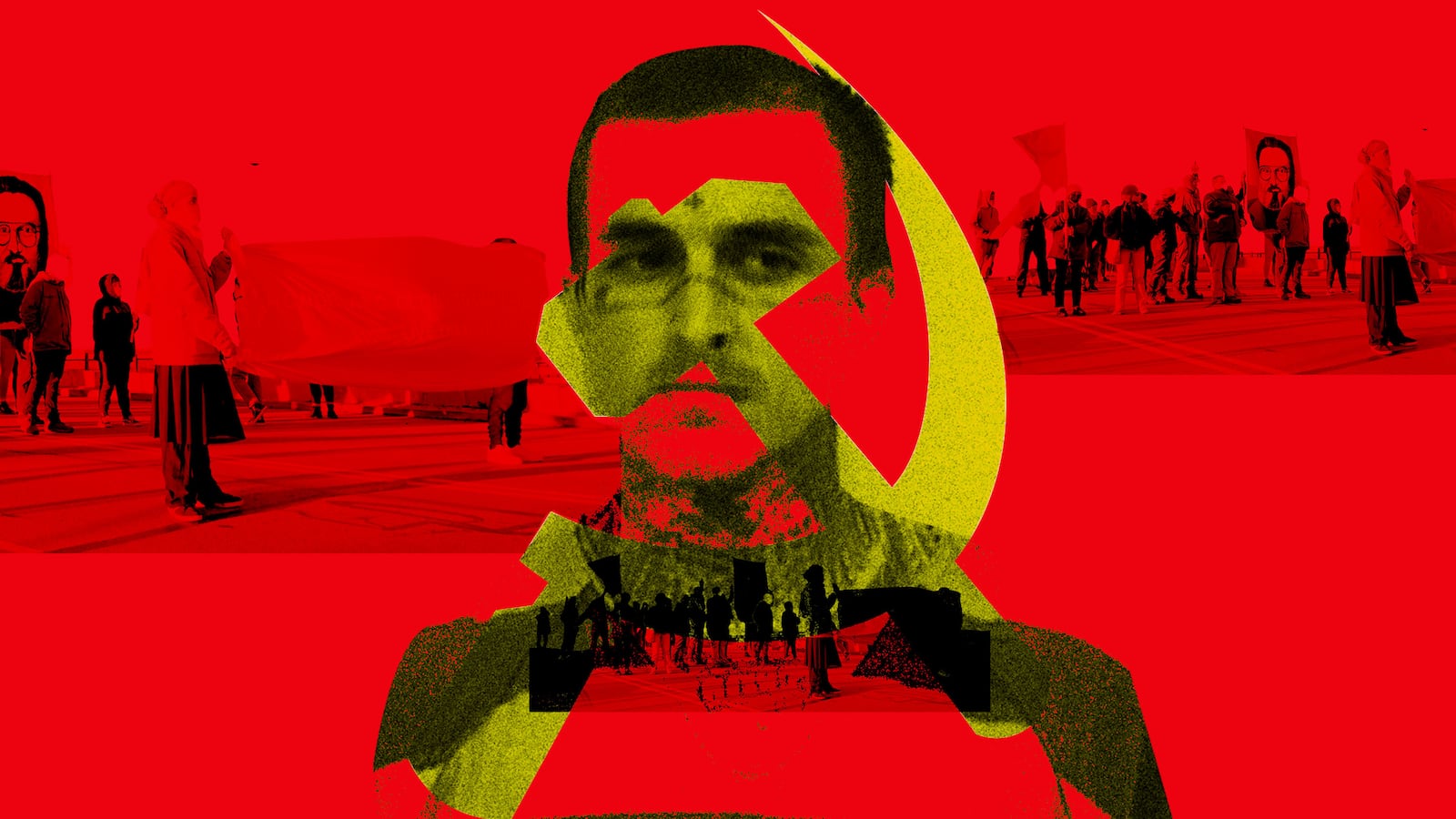

Austin, who requested to withhold his full last name for safety, is a former member of Red Guards, a multi-city Maoist group that made headlines in 2020 for its aggressive disruptions of other leftist organizations and candidates. Now, a year after the group’s 2022 implosion, former members like Austin say they were victims of a coercive club that dictated where members could work, whom they could date, where they could live, and how they could behave, while meting out draconian punishments on members who disobeyed.

At its top was a charismatic chairman named Jared Roark, whose guilty plea and imprisonment on gun charges in 2021 sent Red Guards into disarray. But after Roark’s release from prison this year, his former followers are trying to warn new potential recruits.

“I was incredibly, incredibly swayed by Jared,” Luke, another former Red Guards member, told The Daily Beast. “I was a really well-cooked cult member.”

If the group hadn’t relocated Luke from its Texas hub to another city as punishment for dating an unapproved person, Luke said, “there’s a good chance I might still be following him.”

Luke, like all former Red Guards members interviewed by The Daily Beast, requested to withhold his full legal name, due to fear of reprisals from former comrades. That threat was explicit in Red Guards literature.

“Former members who divulge internal information must be dealt with and must be considered informants and snitches,” reads a 2020 manual from the group. “All possible levels of revolutionary violence must be used to retaliate against those who dare to talk about the organization’s secrets. If it is possible to get away with it, that is the appropriate level of violence. In some cases, when the discredited comrade turned enemy poses a significant risk to the overall organization, no cost is too much and comrades must be selected or volunteer to annihilate traitors.”

Roark, 41, could not be reached for comment for this story. Family members either did not return messages or told The Daily Beast they’d lost touch with him. A Texas car shop that lists Roark as an employee told The Daily Beast that he’s no longer with the company. Former Red Guards members, including those who remain close to the movement, said they could not contact Roark, who changed numbers frequently even before prison.

His old blog has been taken over by ex-Red Guards members who have updated it with a long statement claiming that the group’s “opportunist leaders were cruel, callous, and vindictive. Our comrades are traumatized, demoralized, and physically ill due to their actions.”

Red Guards, by its own description in early blog posts, began around 2014 as “no more than three comrades who were gradually gravitating towards Maoism at various levels of development.” Still in its infancy, the group collaborated with other organizations across the leftist spectrum, appearing at racial justice and women’s rights demonstrations in Austin, Texas.

After their bright red flags began to attract notice at protests, the fledgling group realized it should beef up its branding. “We needed a name and to consolidate our ideology,” a 2016 blog post from the group reads.

For a name, they landed on Red Guards Austin. For an ideology, they landed on Gonzaloism: a branch of Maoism developed by Peruvian guerrilla leader Abimael Guzmán. Guzmán, known to followers as Presidente Gonzalo, was the leader of the Shining Path, an insurgent Maoist group whose fighters killed tens of thousands during an armed uprising in the 1980s and ’90s.

Even within the small world of American Maoism, Gonzaloism is controversial. Its critics say it elevates strongmen, fosters cults of personality, and encourages hostility against other leftists over minor differences of political thought. But not everyone who joined Red Guards was schooled in niche Maoist doctrine.

Luke was 19 when he first came into contact with Red Guards in 2016. His politics were less radical at the time—“sort of generic liberal activism”—but his then-partner was a fan of the Red Guards, which by that point was beginning to show up at protests and “make a huge scene.”

Luke got involved, at first through Red Guards’ reading groups, then through its charity initiative which distributed free groceries. “It was starting to feel like we were becoming friends pretty fast,” he said, describing “tons of love-bombing. I felt like these were my new best friends.”

That summer, something shifted. “Things really ramped up,” Luke said. “The way I look at it now, I think Jared sort of realized that, ‘Oh, these really impressionable people who don’t know much about politics are showing up to this now, and we can use their energy.’”

Some of that energy went into front groups and splinter cells, in Texas and other cities like Pittsburgh. It was there that Austin D., frustrated with his job, took up his coworker’s advice and read some of Mao’s political texts. He found them surprisingly approachable.

“Just for the heck of it, I’m going to do what Mao says,” he recalled telling himself. “I’m going to apply the theory to practice. Our work conditions at Starbucks really suck. I’m gonna do some of these things Mao recommends for strategy and see how that applies to Starbucks.”

Mao’s tactics took the Starbucks branch by storm. An unofficial union formed, and employees planned protests. “We actually managed to get our really awful boss fired,” Austin said. “I credit that as an actual proof that won me over while I was still in critical thinking mode.”

When Austin’s coworker invited him to a study group and a charity organization run by Red Guards, he went along. And although Austin was initially lukewarm on the group, he joined in earnest in 2020, when a breakup, COVID-related unemployment, and a front-row view of police brutality at Black Lives Matter protests combined to send him looking for “a greater purpose.” He leased a larger apartment than he strictly needed, and opened it up to roommates and visitors from Red Guards.

Not all Red Guards associates knew they were participating in the group. One, a Texas-based woman who asked to withhold her name due to safety concerns, said she became involved with Red Guards in 2020, through a protest group that formed after police shot and killed a local man.

Unbeknownst to the woman and some of her comrades, the group was an arm of Red Guards, the former member told The Daily Beast. “It was unknown to us that it went higher,” she said, although as the summer of protest progressed, she began to have suspicions.

“We asked at one point during a meeting. Just like, ‘hey, I’m just curious, what’s the story with Red Guards?’” she recalled asking. “‘Is this connected to them in any way?’ They claimed no, and that was that.”

But the question, she thinks, put her in the bad books with an upper management she didn’t even know existed.

“I think I was noted internally as being untrustworthy, or kind of suspicious. Because I asked that question. More than once.”

When Luke joined Red Guards, in 2016, new recruits were still likely to meet Jared Roark, the group’s leader. He was a polarizing figure.

“I tried to explain this to people the other week,” Luke told The Daily Beast in early September. “Because once pictures of Jared started circulating online, a lot of people were like, man, who would ever follow this guy?”

By 2016, per a mugshot that year, Roark had short, dark hair and a faint mustache. He had a small cross inked on his forehead, reminiscent of Charles Manson, with a long, thin tattoo running ear to ear across his nose, and another tattoo beneath his right eye. He came from a punk scene and looked the part, to the intrigue of young activists like Luke.

“The thing is, in contrast to that, he can be incredibly approachable and friendly when he wants to be,” Luke said.

But Roark’s image changed after Donald Trump’s election. On Nov. 13, Red Guards attended an anti-Trump protest in Austin, where Roark knocked off a counter-protester’s “Make America Great Again” hat, former Red Guards said. Other people reportedly ripped up a sign the Trump fan carried. Police rushed the crowd. One tackled and pinned Roark, breaking the C3 and C4 vertebrae at the top of his neck.

Roark was arrested, charged with resisting arrest, and found not guilty. The violence of his ordeal bolstered his radical credentials among some followers.

“Following his arrest, he started to be more and more promoted as this revolutionary hero,” Austin said. “He’s been imprisoned for the cause and he had his neck broken by police and he was essentially mythologized.”

Roark also began acting more like a revolutionary under siege. “At that point he went more underground and there were policies rolled out to compartmentalize each group,” Austin said.

Already, Red Guards had been ramping up its recruitment efforts, Luke said. In 2016, the group launched “Cadre School,” an intensive, month-long, 24/7 training camp, where participants trained in physical fitness and Maoist political thought. They also learned to apply the theory of struggle not just to political battles, but to their personal problems.

Red Guards taught a version of Maoist dialectics that held that the revolutionary fight between capitalism and communism was also playing out in the worker’s mind.

“As a revolutionary you’re supposed to weed out the capitalist worldview or bourgeois worldview and become purely someone with a proletarian, revolutionary worldview,” Austin explained. “Self-criticism is a big part of it.”

Testimonials of Cadre School attendees, published by Red Guards, boast of learning to subsume one’s will to the group.

“What I’ve learned in Cadre School is, in a word, how to be a good communist,” one testimonial read, adding that they’d learned “a high level of discipline and willingness (if not an eagerness) to both submit one’s thoughts to the collective in order to boost two-line struggle and criticism/self-criticism”

Another testimonial writer said, “I eventually reached a crisis point where my inner bourgeois self and my communist self came to the fore as an open antagonistic contradiction that demanded resolution. Through the help of my comrades here, I have since engaged in a process of thought reform to enable my communist self to overcome my bourgeois self. This means that I have started to learn how to turn Maoism inwards, instead of it being something that I only projected outward into the world.”

Coincidentally or not, multiple former Red Guards said, the process of purging oneself of unapproved thoughts accompanied severe, sustained sleep deprivation.

After Austin became fully immersed in the group in 2020, it consumed his waking and nighttime hours. He got a job at Amazon “because the cult wanted to organize it” and spent his working days pulling double-duty trying to get fellow workers involved in the cause. Outside of work, he’d report on two to five demonstrations each week for the Red Guards’ news site, each of which took hours of time. Saturdays were occupied by a mandatory three-hour study, in addition to a study group he was asked to run for activists that he’d been tasked with recruiting. The group also expected him to help create signs and banners, and to participate in multiple late-night demonstrations each week.

“That leaves you going to bed at 2:00 a.m. or sometimes 4:00 a.m. and then waking up at six or seven whenever you have to go to work,” he said.

Burnout was endemic, including in Red Guards front groups, said a Texas activist who worked for one of the organization’s publications.

“Basically they told us, ‘Here’s the correct political position on the topic of burnout: burnout is not real,’” the former member told The Daily Beast. “It's a way that people can basically tap out of their obligations as revolutionaries. They were like, ‘We do not even support the use of the word burnout because it’s not a Maoist concept, it’s a postmodernist concept.’”

Eventually, members couldn’t keep up.

Luke was attending daily protests with Red Guards in July 2020 when one ended in a murder.

As Luke marched with Black Lives Matter protesters on July 25, a self-described “racist” who had previously written about murdering protesters, and who compared Black people to “monkeys,” drove his car into a crowd of marchers. Garrett Foster, a 28-year-old protester who was legally open-carrying a gun, approached the car. The driver, Daniel Perry, withdrew his own gun and killed Foster. Perry was later convicted of murder. (Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has since instructed the state’s parole board to consider an expedited pardon for Perry.)

The murder left Luke shaken. “I didn’t know how to deal with that,” he said. “I tried to keep doing all the work like I was supposed to. And pretty immediately it was clear that it was not up to the par that they were expecting.”

To address Luke’s apparent shortcomings, Red Guards leadership convened a “struggle session.”

Under Mao, the struggle session was a public ritual designed to humiliate perceived “class enemies.” During these episodes, subjects might undergo a range of punishments before a large crowd, including having their alleged misdeeds shouted at them or being made to wear demeaning signs and clothing (dunce caps were a favorite). Some sessions turned violent. Some struggle session victims died by suicide soon thereafter.

The Austin-based Red Guards put their own spin on struggle sessions. During those sessions, a member would be made to stand for nearly an hour without speaking as peers berated them for perceived faults. The effect, Austin said, was intended to break down the victim. He recalled attending one session in which a comrade was accused of making banners poorly. The accused was made to stand with his bad artwork draped around his shoulders while peers made fun of him.

After the first round of critiques, the subject was allowed to answer.

“You had a chance to respond and you were kind of screwed either way because if you responded accepting the criticisms and saying you wanted to change, then everybody would jump on you again because you were too quick to accept,” Austin said. But defend yourself and “you’d really get attacked because you’re going against the whole collective and you’re being a bourgeois individualist.”

The event usually lasted three hours, after a back-and-forth that resulted in victims leaving with “this completely broken attitude,” Austin said, likening those people to “a kicked dog. The head would be hanging down and you could see it in their body language for weeks after that.”

At least two struggle sessions turned violent. In one, Luke said, a member of a student group was physically attacked by his interrogators. The young man soon agreed to the group’s demands that he change his behavior, but “obviously he was just trying to get out of there,” Luke said.

“Once he was out of there, he texted the people he was meeting with and said, ‘I’m moving to another state and I’m never going to see you again.’”

On another occasion, Luke and Austin said, a male colleague was accused of cheating on his girlfriend by making advances on a younger member. As punishment, the man was tied to a chair and beaten by female members of Red Guards. The assault left the man with at least one broken rib.

In the following weeks, Austin said, “He had to wear a T-shirt and anybody could write things on it like ‘you pig’ and all kinds of derogatory things about him, calling out his behavior. He had to wear that in public and at events.”

When Luke’s performance appeared to lapse after Garrett Foster’s murder, he, too, was called in for a struggle session. When the session ended, leadership prescribed a “rectification” plan: a series of instructions supposedly designed to correct his behavior.

In other cases, rectification might include wearing the “you pig” shirt in public, doing more work for the group, moving to another city, taking a job with less pay, participating in grueling physical exercise, or swimming in the chilly waters of Austin’s Barton Springs.

In Luke’s case, rectification meant that Red Guards leadership “rescinded permission” for Luke to date his now-fiancé, who was also a member of the group.

But Luke didn’t end things. How could he? He lived with his partner. Eventually, he self-reported their continued relationship.

“I ended up feeling guilty about that,” he said. “And so I kind of snitched on myself. Within about 24 hours, they told me I had to move across the country, basically, to a different city. I didn’t speak to him for a year and a half, until the cult ended.”

Red Guards members weren’t the only parties facing the group’s wrath. Other organizations on the left were frequent targets of disruption by Red Guards—especially if Red Guards deemed those groups insufficiently revolutionary.

In Jan. 2020, Austin-area activist Heidi Sloan was one of the left-most candidates with a possible path toward Congress. Sloan, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), made national headlines running on issues like homelessness and affordable housing in Texas. She also made enemies within the Red Guards.

While leaving a campaign event that month, Sloan was surrounded by masked members of the group, who reportedly shoved her, threw leaflets at her, smashed an egg full of red paint on her head, and loudly denounced “bourgeois electoral politics.”

On Twitter shortly after the attack, Sloan identified Red Guards as the culprit, calling the group “a radical cult in our city that suppresses democracy.”

The incident was not Red Guards’ first attack on other left-leaning organizations, or even on the DSA, Sloan noted. “They have come to disrupt DSA’s educational events, hung a pig’s head outside of a public library, tagged the [labor union] AFL- CIO with graffiti, and disrupted other organizations’ community events.”

Red Guards did not shy away from the allegations. In a 2018 blog post, the group published a picture of a bloody pig’s head hanging on a building with a sign (written in blood, or something that looked like it) reading “DEM SOC OF AMERICA ARE CAPITALIST PIGS.”

“While the DSA squirms, we will continue bringing real Marxism to the masses,” the Red Guards post read. “Militants placing pigs heads outside of DSA events is but an act of protest, exposing them for the pigs they are and treating them as such”

The group also confronted DSA organizers in Kansas City in 2019, where Red Guards members in red balaclavas ransacked a DSA event, in footage that went briefly viral on the left. Although the footage appears to have vanished from the internet, surviving screenshots show two DSA members on the ground, amid scattered pamphlets, while three Red Guards members stand over them. The physical attack sent a DSA member to the hospital, the democratic socialist group claimed in a statement.

Red Guards also published footage of members confronting members of the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) at a protest, reading the group a list of demands, tearing a megaphone from a PSL speaker’s hands, and burning PSL signs. Former Red Guards members also said the group had targeted a Los Angeles-based anarcha-feminist collective, nailing dead rats to their meeting space. (The Daily Beast was unable to confirm the incident and the collective did not return a request for comment.)

Red Guards could disrupt other groups on the left. But some members began to question whether the organization could actually lead the country to Maoist revolution.

The writing was on the wall during a rural retreat in 2021, where leaders hadn’t purchased enough eggs, said the Austin-based activist who’d worked on the group’s new site.

An experienced cook, she had volunteered to prepare food for the approximately 60 people who’d convened for the three-day gathering. But as she readied a meal, she noticed that the group didn’t have enough food for all its members. When she notified a leader about the shortages, he argued with her, telling her the group’s political work would keep it too busy for a grocery run.

“I’m like, ‘I don’t know what to tell you. I know how to cook. I know how to cook for large numbers. You don’t have enough eggs if you want everyone to have breakfast like you promised them, and you’re holding them hostage out here in the country without cellphones,’” she remembered telling him. “‘You need to buy more eggs.’”

She eventually won the battle and breakfast was served. But “the thought that went through my head was, ‘These are supposed to be the most serious communists in the country, who want to reconstitute a communist party and support the idea of armed revolution… I was like, OK, these are not serious people.”

In fact, Red Guards was undergoing organizational upheaval that stripped the group of its frontman.

In February 2018, Roark and his wife, Lisa Hogan, were having a falling-out with another couple from the activist scene, according to court documents filed on Roark’s behalf. “The couples grew apart and Hogan asked [the couple] to return a set of books,” the documents read.

When the couple arrived at Roark’s home, Hogan struck the other woman in the head and continued trying to punch her, a victim told police, according to a police report. (Hogan did not return requests for comment and Roark’s attorney previously cast doubt on Hogan’s alleged attack, noting that she was three months’ pregnant at the time.)

When the woman’s boyfriend, Jesus Mares, got out of his car, Roark allegedly pointed a gun at his head.

“Get back in the car,” Roark told Mares, according to Mares’ account to police. “Get the fuck out of here.”

Mares said he was not leaving without his girlfriend. It was then, Mares alleged, that Roark struck him in the head with the gun. “I thought I was going to die,” Mares told police.

Roark was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon—a charge that was later dismissed. But Roark was not supposed to have guns at all. In 2003, he’d been convicted on a felony count of graffiti on a place of “worship/burial/public monument/school.” The felony conviction meant he could no longer own firearms. And when police arrested Roark on the assault charge, they found a collection of firearms in his home.

He was convicted on gun charges, and began a prison sentence in March 2021.

With Roark behind bars, Red Guards leadership passed to others in his inner circle. The strict discipline and grueling volunteer requirements remained. If anything, Austin and Luke said, the workload increased. But without Roark to enforce order, Red Guards members had “a little more space to criticize things that had been happening in the group,” Austin said.

Members raised concerns and sentenced their interim leader to rectification. Roark’s wife, Hogan, was suggested as a replacement, but she informed Roark of growing dissent in the ranks, prompting him to write an angry jailhouse letter calling out underlings.

“Several of the leaders were scared,” Austin said. “They left. They just vanished.”

Ultimately, in the spring of 2022, some local leaders went rogue. “The leadership in Pittsburgh basically said, ‘We’re not gonna follow their orders anymore, and just see what happens,’” Luke recalled.

Those leaders were soon summoned to Texas, where Red Guards’ top brass held a summit. There, organizers raised the issues of chronic burnout within the ranks. Members were falling ill from lack of sleep, overwork, and poor communal living conditions, they said. Women were treated unfairly in the group, expected to perform more domestic and administrative tasks while men were more often viewed as leaders. Members were broke and isolated, not eating enough, estranged from romantic partners.

The regional leaders decided to put the group’s future up to its members in local chapters.

In Pittsburgh, “They sat people down and were like, ‘Here’s what was really going on behind the scenes, and where’s what we learned while we were in Texas. Do we want to keep going with this project?’” Austin recalled.

“Pretty immediately everybody was like, ‘No.’”

Former Red Guards remember feeling a mix of liberation and loss at the group’s dissolution.

Luke recalled a conversation with a comrade shortly after Red Guards’ dissolution. “I was like, ‘I started this painting of Chairman Gonzalo before things ended and I don’t know what to do with it anymore.’”

The friend suggested he deface the painting and turn Gonzalo into a clown. “I found that just sacrilegious,” Luke said. “I was like, oh god, I can’t do that to him… Things like that just seemed very scary for a while.”

But eventually he began connecting with other former members and discussing his experiences—something that Red Guards’ intense secrecy and strict hierarchy had previously made difficult. He began reading about cults, and says he recognized striking similarities to Red Guards tactics. And he reconnected with the partner from whom he’d been forcibly separated when Red Guards rescinded their dating rights and sent Luke packing to another city.

“We would talk on the phone for hours,” Luke said. Sometimes those calls were contentious. Luke was still sympathetic to Red Guards while his now-fiancé had made a hard break from the group.

“He asked, ‘What is the point of all this for you? I don’t get it.’ And I just said, ‘I want people to be afraid of being bad.’ That was pretty revelatory for me.”

Today, Luke, Austin and other ex-members are part of a group chat where they piece together their experiences. They’ve had to resist politicizing the group, they said; even after a year, it’s still easy for them to suggest a study session when problems arise. When Luke recently recommended they read a book together, “They were like, ‘No. Let’s just be friends. Let’s just hang out.’ That was a new idea.”

Some former members, however, have dropped off the political map. Many are women, said the former associate who’d written for the Red Guards’ news site.

“Basically all women that I knew from those times, regardless of which [front] group they were in, they’ve pretty much all gone no-contact,” she said.

“They’ve shut off their email. They’re not reachable. They have been, my perception is that they’ve been so burned and, like, used and disrespected in various ways that they just can’t bear to talk or think about this stuff anymore.”

Austin said he hopes Red Guards’ implosion might hold lessons for other people in the crosshairs of cults.

“What does democracy look like in your organization?” he encouraged other political activists to consider. “I think it’s a good question to be asking.”