Standing outside one of the main buildings on the University of Connecticut campus last week, Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus task force coordinator, let out an exasperated sigh through her peach-colored face mask.

Birx had been traveling almost non-stop since June, working with local and state officials to develop area-specific strategies for slowing the spread of the highly contagious virus. Connecticut was her 32nd state and, as in the others, she was peppered there with questions about the mixed messaging stemming from the White House.

Seemingly frustrated by the fact that, 200,000 deaths later, there was still uncertainty about the federal government’s COVID-19 prevention strategy, Birx paused before laying out, yet again, her broken-record response: Wear a mask, wash your hands, and stay socially distanced. Wear a mask, wash hands, social distance.

“We have been able to give our best public-health and scientific advice to leadership and... I continue to do that every day whether it is the governor, whether it is the president, or whether it is members of the community. The consistency of that message is absolutely key,” Birx said. Pressed again on whether masks were necessary, the task force leader rolled her eyes: “Let me make it clear: We know how effective these are in blocking our droplets. It’s not just theoretic[al].”

Birx’s frustration may have been months in the making. But the context was unavoidable. Just days prior, President Trump had returned home from Walter Reed Medical Center and, still infected with the virus, triumphantly removed his mask on the balcony of the White House for prime-time television.

It was a move directly at odds with the caution that Birx and others have been pitching. But while she may have seemed irritated by it all, she was hardly the only high-ranking health official indicating that they’re at their wits’ end with Trump.

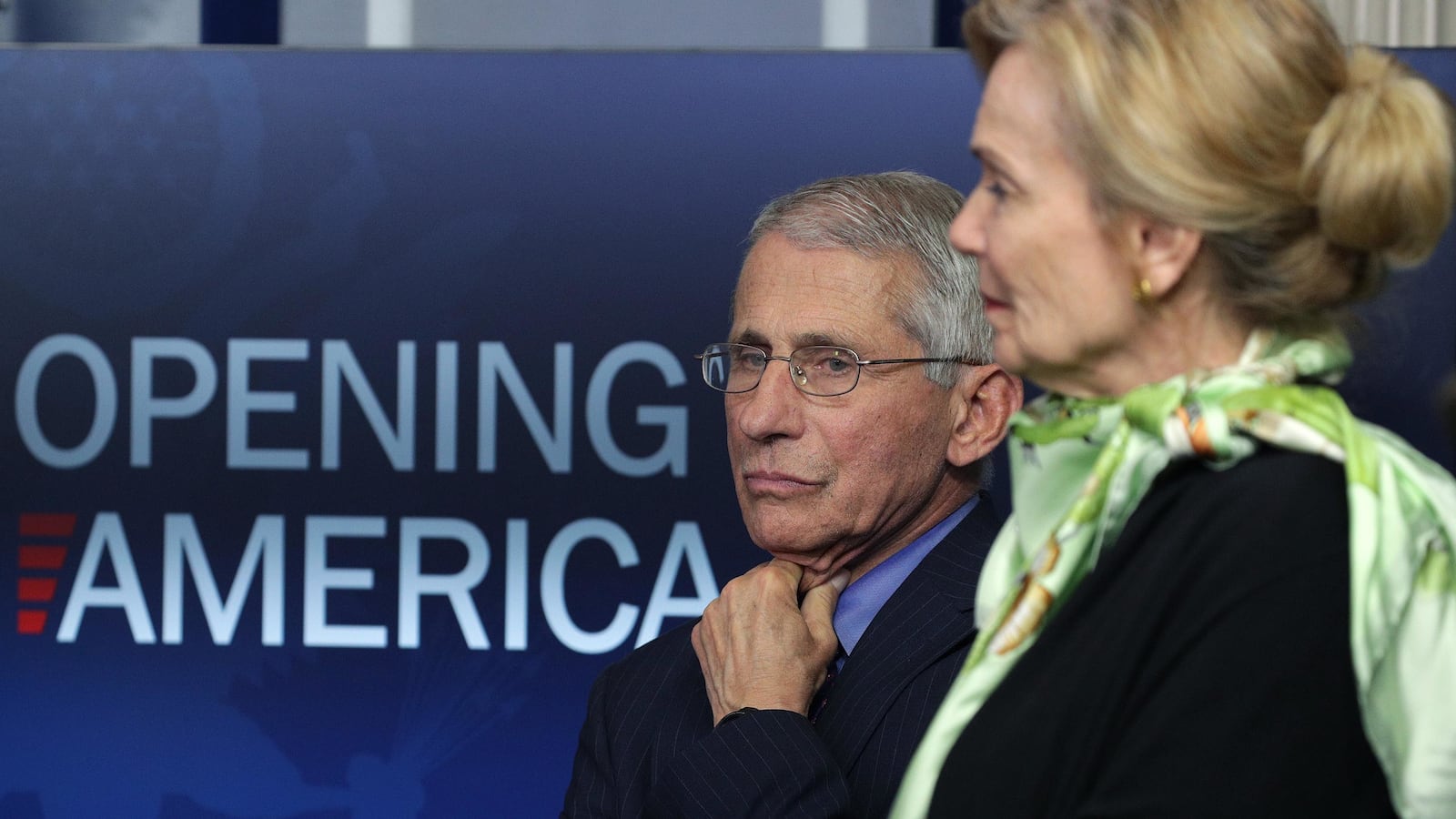

After months of trying to avoid direct run-ins with the president, task force officials are no longer tiptoeing around his demands. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Health and Infectious Disease, has for weeks spoken out against Scott Atlas—a neuroradiologist who has no experience dealing with infectious diseases but has become Trump’s coronavirus guru by feeding his desire for positive news—for “cherry-picking data.” More recently, he’s railed against the Trump campaign for “harassing” him in their ads.

Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has gone after Atlas as well, claiming “everything he says is false;” the CDC has pushed back against the White House’s preference to not recommend testing asymptomatic individuals. And despite demands by the White House that they remain under wraps, guidelines for COVID-19 vaccine-makers that would make a release before the election virtually impossible were published last week by the Federal Drug Administration.

Asked for comment about the increasing frustration among officials, White House spokesperson Brian Morgenstern did not directly speak to the task force tensions and instead said, “President Trump’s top priority is the health and safety of the American people.”

Morgenstern did acknowledge that Trump sometimes disagrees with task force officials “in good faith.” But prior administration officials say such crosscurrents and rebukes from senior health officials are basically unheard of. And they point to a growing rebellion among the ranks of the president’s coronavirus task force right at an increasingly precarious moment: the start of the fall season when cases are on the rise.

“In prior emergencies with which Dr. Fauci and Dr. Birx have been through, there have been better and worse responses, but they’ve all shared some fundamental basic competence. The plain fact is the administration’s response to COVID has lacked basic competence,” said Tom Frieden, former director for the CDC for the Obama administration. “It’s true today there is no national plan, no clear organization, we’re not on the same page and there’s a failure to communicate. There has not been consistent messaging from the federal government. Plus, there has been a politicization of mask-wearing and a lack of discipline in thinking about when to close and what to open. It’s mind-boggling.”

The relationship between Trump and his COVID advisers has always been fraught. The president painted a rosy scenario about the fight against the virus since it arrived in America. He’s openly pushed for reopening the country on an expedited time frame. He’s accused career scientists of plotting against him by dragging their feet on a vaccine. And he’s improvised about the efficacy of therapies and treatments in ways bordering, experts say, on the irresponsible.

But the frictions have become particularly pronounced in recent weeks, after the White House hosted what Fauci called a superspreader event and as the election has neared.

“I think, genuinely, both Redfield and Birx want to do good,” said Zeke Emanuel, a former health policy adviser to the Obama administration. “But trying to figure out how to do good in this administration has been complex for them.”

With Trump increasingly turning to Atlas for guidance, Birx, Fauci, and Redfield have all been sidelined from the task force. In recent interviews, Fauci has explicitly said that the task force isn’t even meeting as often as it did, sometimes once a week. Birx has been on the road, participating only in local media interviews. Redfield, meanwhile, has participated in virtually zero media appearances after a recent series of run-ins with the White House over mask-wearing, testing and school reopening guidelines, even as the former director of the CDC, William Foege, sent a public letter urging him to “stand up to a bully.”

But as they’ve slipped away from the limelight, the trio and others have been more adamant in holding their ground on policy disputes. And for those who have been in the bureaucratic trenches at the intersection of politics and health policy, it’s been something of a pleasant surprise to see the absence of acquiescence.

“I have a lot of respect for Deborah Birx and I think she does have an understanding of what needs to be done. I think she does do her best to go out and explain those messages. Because the science is not that complicated anymore,” said Andy Slavitt, Obama’s former director of the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. “I suspect she feels like it’s important for her to be there and she views herself as a public-health warrior. But I think there is a limited amount that they can do without the support of their boss. So they got to make do with the person who sits in the Oval Office. I think she’s facing those very consequences but she’s doing what maybe the most productive thing she can.”

Fewer people on the task force have been more openly defiant of Trump in recent days than Fauci. The revered infectious-disease expert has not shied away from issuing dire warnings about the current course the disease is taking. But he’s also been far more willing to dispense with the type of diplomatic niceties that marked his public utterances about the president and the White House during the pandemic’s early months.

In an interview with The Daily Beast in September, Fauci cast doubt on the president’s timeline that a COVID-19 vaccine was just around the corner and pointed to a significant lack of trust in the vaccine process. In another interview with the Beast on Monday, he took his biggest jab yet at Trump and his campaign, demanding that they refrain from using him in future campaign ads.

“By doing this against my will they are, in effect, harassing me,” Fauci said. “Since campaign ads are about getting votes, their harassment of me might have the opposite effect of turning some voters off.”

While part of the friction may stem from the task force’s continued difficulty in getting the pandemic under control, officials working with the administration say much of it is caused by Trump, whose attention to and understanding of the virus has always been a source of frustration.

“As the election heated up, it got harder to get him to focus on the guidelines and data that we believed to be most important to saving lives,” said a senior administration official who works with the White House task force. “That is still the case now. It has been known that if you’re bringing something to him that isn’t likely to help his re-election or get the economy open [to his liking] again, then you might as well not be presenting it to the president at all.”

That sentiment was underscored Monday night, when Trump returned to the campaign trail, at a Sanford, Florida, rally, for the first major event of its kind since he was hospitalized. On stage, he cracked jokes about his perceived “immunity” from the virus, how he’d “kiss every one in that audience,” including “all the guys and the beautiful women,” and continued calling for the fast reopening of the U.S. economy to “get our country rolling.”

To veterans of the coronavirus task force turned critics of the president, it was a mere extension of the unserious manner in which he’s dealt with the emergency since Day 1.

Olivia Troye, a former senior adviser for the task force who left in August and has since endorsed 2020 Democratic nominee Joe Biden, recounted how the president would show up to coronavirus meetings and repeatedly ask things like, “Is this worse than the flu?” and “Children aren’t affected, right?” only to be told that children could indeed be affected.

“[He] would kind of nod along, but then he’d go out in public and say the opposite, anyway. This would happen all the time, and it was infuriating,” she said. “Dr. Fauci would tell the vice president and some of the president’s senior staff that children could be major spreaders of it because the data is inconclusive, only to see the administration and Trump completely disregard it, over and over again.”

Troye recalled that in some meetings with members of the COVID task force earlier this year, the president would routinely get distracted and instead “want to talk about media that had pissed him off.”

“At times, he would go around [the room] and spend his time complimenting people for their [recent TV] appearances. He’d compliment Kellyanne Conway, or someone, on how well he thought someone did, saying, ‘Oh, you did a great job on that today!’” she added. “This was [during meetings] when we were trying to get him to focus on matters of life and death around the country.”

Conway did not return a request for comment.

That task force members are now more forcefully pushing back against Trump doesn’t strike some as a surprise. But for other onlookers, kudos are not exactly earned at this juncture. The time for speaking out and pushing back, they say, should have been months ago.

“I think aside from Fauci, they are still not speaking out or speaking the truth to the American people,” said Leslie Datch, who ran the Ebola response at the Department of Health and Human Services during the Obama administration. “I think Trump bringing COVID-19 into the White House, the intensifying epidemic around the country, and Trump’s doubling down on his craziness after his illness, has shown them that he will never do the right thing. Any glimmer of hope or sanity has been removed. If you have any fidelity to the truth, to the Hippocratic oath, or to the principles you tell yourself and your family are important... it’s become impossible to remain silent and be complicit.”