On June 6, 1944, Franklin Roosevelt went on the radio and led the nation in prayer. Avoiding any trace of bluster, he asked not for conquest but for a better world.

With over 370 World War II vets dying every day, this year’s 75th anniversary of D-Day has a special poignancy. It reminds us that all those who on June 6, 1944, landed on the Normandy coast and began the last phase of World War II in Europe will soon be gone.

Like Gettysburg, D-Day marks a turning point in American history. In the case of Gettysburg, our memory of the battle is inseparable from the address President Abraham Lincoln delivered there four months later in November 1863. But it is often forgotten that D-Day, too, was memorialized in the year it took place.

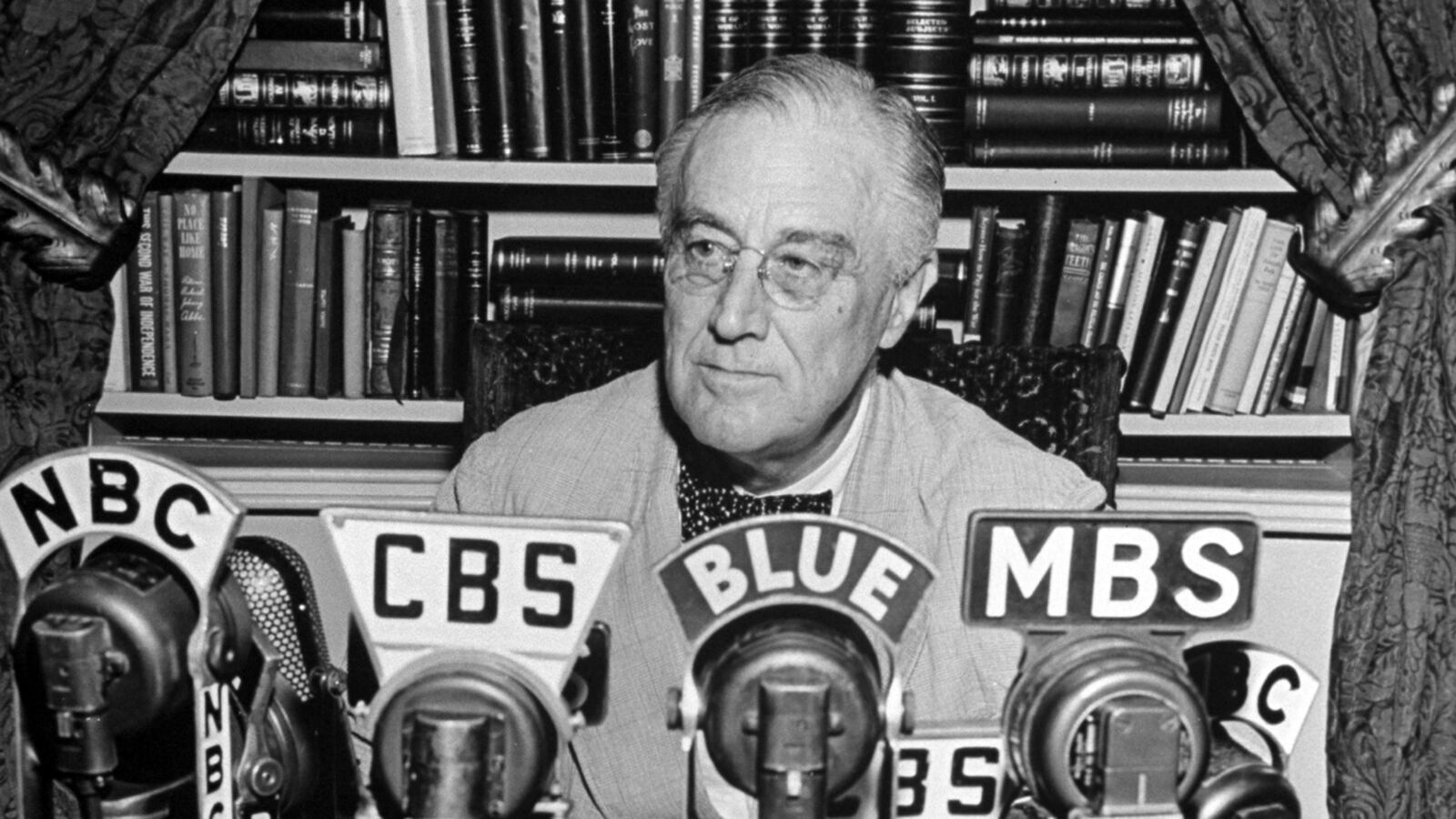

On June 6, President Roosevelt read over nationwide radio a prayer that earlier in the day the White House had sent to newspapers across the country. As Nigel Hamilton notes in his brilliant new book, War and Peace: FDR’s Final Odyssey: D-Day to Yalta, 1943-1945, Roosevelt had put much thought into his D-Day prayer. He had composed it during a quiet weekend stay at the Charlottesville, Virginia, home of his military aide Major General Edwin ”Pa” Watson.

This year as we mark D-Day, Roosevelt’s prayer is worth recalling for what it says about how we ought to conduct ourselves as a nation, especially in foreign affairs. Delivered from the Diplomatic Reception Room in the White House at 8:30 p.m., the prayer was one that FDR read in a tone more suited to a church sermon than a political address. “And so, in this poignant hour, I ask you to join with me in prayer,” the president began.

Like Lincoln, Roosevelt emphasized the importance of victory, and in his prayer he requests God’s help for the troops engaged in the D-Day invasion. “Lead them straight and true: give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith,” the president asks.

Central to Roosevelt’s prayer, as it was to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, is the idea that victory offers the chance to create a new and better world. “They fight not for the lust of conquest. They fight to end conquest,” Roosevelt says of America’s troops.

Lincoln spoke about the Civil War preserving the values of the Declaration of Independence. FDR saw a parallel historical struggle taking place in World War II. “Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity,” Roosevelt declared.

The D-Day landings cost America and its allies over 10,000 casualties, and in Europe, General Dwight Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, warned the troops in his pre-invasion message, “Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened. He will fight savagely.”

Roosevelt was of the same mind as Eisenhower. He foresaw a long struggle ahead, even as men and equipment poured ashore at Normandy. “This war isn’t over by any means,” the president cautioned the country in his D-Day press conference.

In his prayer, FDR made a point of resisting calls for single day of national prayer, instead observing, “because the road is long and the desire is great, I ask that our people devote themselves to a continuance of prayer.”

Roosevelt believed the end result of the D-Day invasion should not be a Pax Americana. It should be a more just world. “Help us to conquer the apostles of greed and racial arrogancies,” Roosevelt asks in the concluding paragraph of his prayer. “Lead us to the saving of our country, and with our sister nations into a world unity that will spell a sure peace—a peace invulnerable to the schemings of unworthy men.”

For Roosevelt, who would not live to see the end of World War II, making the values of his D-Day prayer a reality was paramount. He began 1944 with a State of the Union Address in which he called for a second Bill of Rights that would provide economic security for all Americans. In late June he signed the G.I. Bill, which, among its other benefits, gave returning servicemen and women the opportunity to continue their educations at government expense. And in August the president helped lay the foundation for what would become the United Nations.

We will never know exactly what the post-World War II era would have looked like had Roosevelt been able to complete his fourth term, but from the Marshall Plan to NATO, it is easy to see how the values of Roosevelt’s D-Day prayer are reflected in American foreign policy of the late ’40s.

There is no turning the clock back to that time, but more than nostalgia is still in order. Today, FDR’s prayer remains a strong rebuke to those who think American military power can be meaningful without being deeply anchored in a moral vision.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American Studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Their Last Battle: The Fight for the National World War II Memorial.