These days few periods in American history hold more interest than the Reconstruction era of the 1860s and 1870s. The struggles with voter suppression laws and the policing of Black communities are all too often nothing so much as extensions of the racial legacy of the post-Civil War era.

It is this connection between past and present that makes Robert S. Levine’s The Failed Promise: Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass, and the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson especially timely. Levine begins by telling us that the promise of Reconstruction “remains unfulfilled to this day,” but it is not a point he has to stress. The Supreme Court’s decision this July 1 upholding Arizona’s new voter restriction laws in the case of Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee is all the reminder we need of how the current battle for Black voting rights goes straight back to 1870 and the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which prevents states from denying the right to vote on account of race or color.

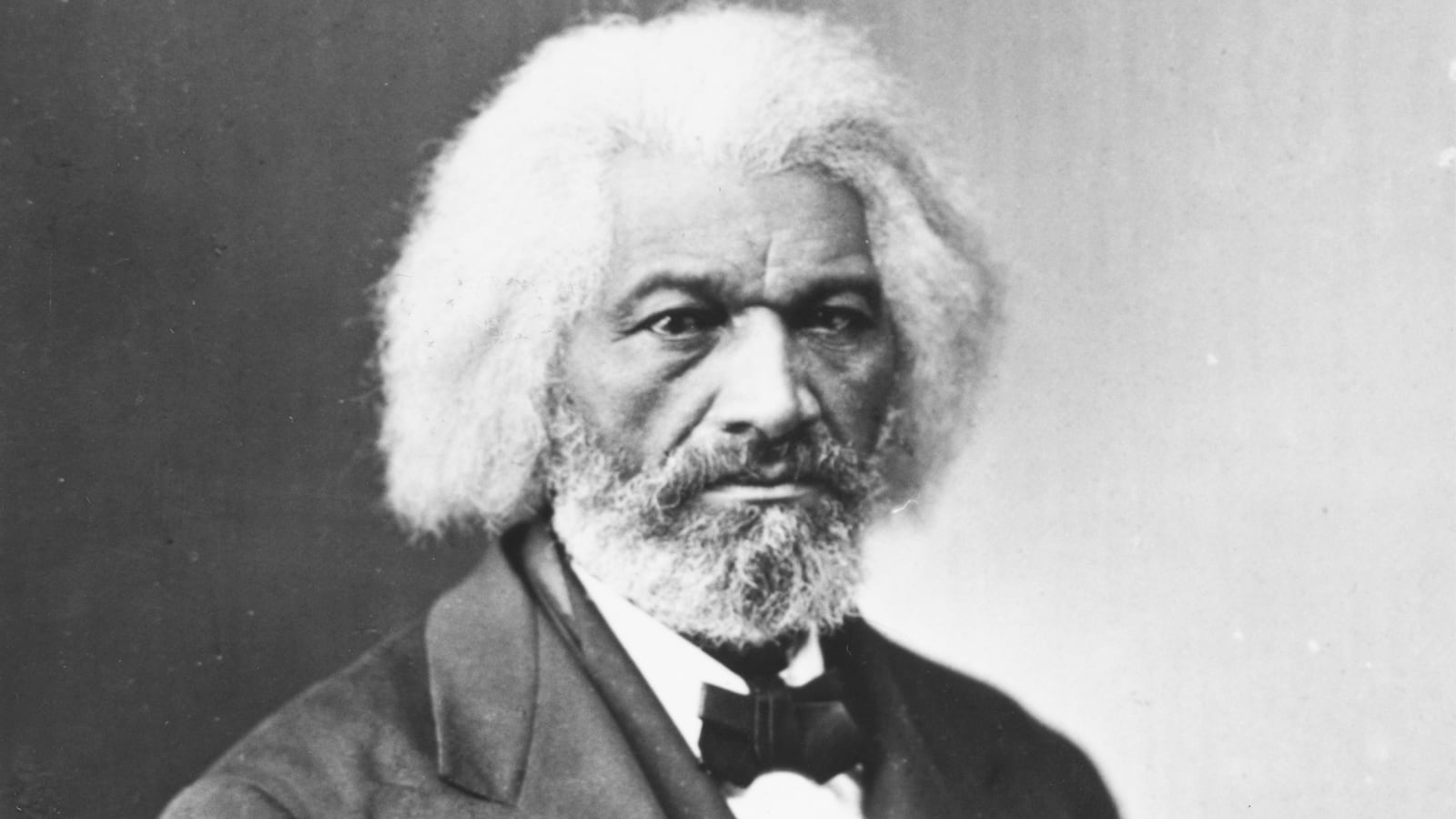

The hero of Levine’s book is Frederick Douglass. In his portrait of Douglass, Levine’s aim is to go beyond the histories of the impeachment of Andrew Johnson, that focus on the Radical Republicans. Levine’s intention is to move Douglass and his African American contemporaries “from the background to the foreground of the four years of Reconstruction under Johnson.”

In Andrew Johnson, Levine has the perfect foil to Douglass. Johnson proclaimed himself to be the Moses who would lead Black Americans to their freedom. He thought of himself as a worthy presidential successor to Lincoln, despite the adverse impact his actions had on America’s former slaves. Johnson saw nothing to regret when in 1865 he issued an Amnesty Proclamation that pardoned most ex-Confederate leaders if they pledged loyalty to the Constitution and the Union. And he saw nothing harmful in his 1866 veto of Congress’s extension of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the key institution for distributing food and clothing to the four million newly freed slaves in the South.

Levine resists the temptation to caricature Johnson. He sees him as a complex figure, noting that after Johnson left the presidency, he made a political comeback, winning election to the Senate from Tennessee. Levine’s point is not that Johnson deserves to be redeemed but that he has been given too much blame for the failures of Reconstruction. “There is something shortsighted in conceiving of the failure of Reconstruction as the fault of one white man,” Levine argues. “The stigmatization of Johnson allows for speculation that a different leader would have guided the nation to interracial reconciliation.”

In Levine’s judgment the Radical Republicans need to be seen as having played a major role in the failures of Reconstruction. Their own racism was a liability that hampered them throughout the post-Civil War years. Levine notes how at the Southern Loyalists’ Convention, which took place in Philadelphia in September 1866, Douglass was treated with disdain. Even before he got to the convention, a number of Republican delegates urged him not to attend because his very presence made so many in their party uneasy.

For Levine, Douglass’ willingness to face down racism from northern Republicans, rather than accept it, was emblematic of his larger vision. Levine emphasizes the distinction Douglass made between theoretical rights and actual right in terms of day-to-day politics. In a lecture he delivered in 1876, the year of America’s centennial, Douglass pointedly asked his white audience, “What does it all amount to, if the black man, after having been made free by the letter of your law, is unable to exercise that freedom?”

In Levine’s judgment what is especially compelling about Douglass is the long view he took of the enduring legacy of slavery. Douglass never lost sight of the time it would take to undo the damage of slavery. “There is no such thing as instantaneous emancipation,” Douglass observed three years after the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery became law. “The links of the chain may be broken in an instant, but it will take not less than a century to obliterate all traces of the institution.”

Douglass’ long view of the legacy of slavery enabled him to keep going at a period in his life when he had every reason to feel discouraged. The surge in lynching in the 1880s and the Supreme Court’s 1883 decision declaring the Civil Rights Acts of 1875 unconstitutional reflected the backward steps the country took in Douglass’ later years. His death in 1895 spared him from having to deal a year later with the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that made “separate but equal” the law of the land, but Douglass would not have wanted to be spared from the fight over Plessy v. Ferguson.

Were he alive today, it is easy to imagine Douglass taking satisfaction in the removal of the statue of Robert E. Lee from its pedestal on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. But his greatest energy would have been devoted to countering the assaults on the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Nothing links Douglass to the present moment more than his belief that the federal government, not the states, must be the ultimate guarantor of voting rights.

John Lewis’ proposed Voting Rights Advancement Act now languishing in Congress—which updates the power of the Justice Department to approve any changes in voting laws in states or political subdivisions with a record of discrimination—would be a common sense remedy to Douglass. He even had a name for what follows when Black Americans are systematically excluded from their right to vote: “emasculated citizenship” he called it.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America.