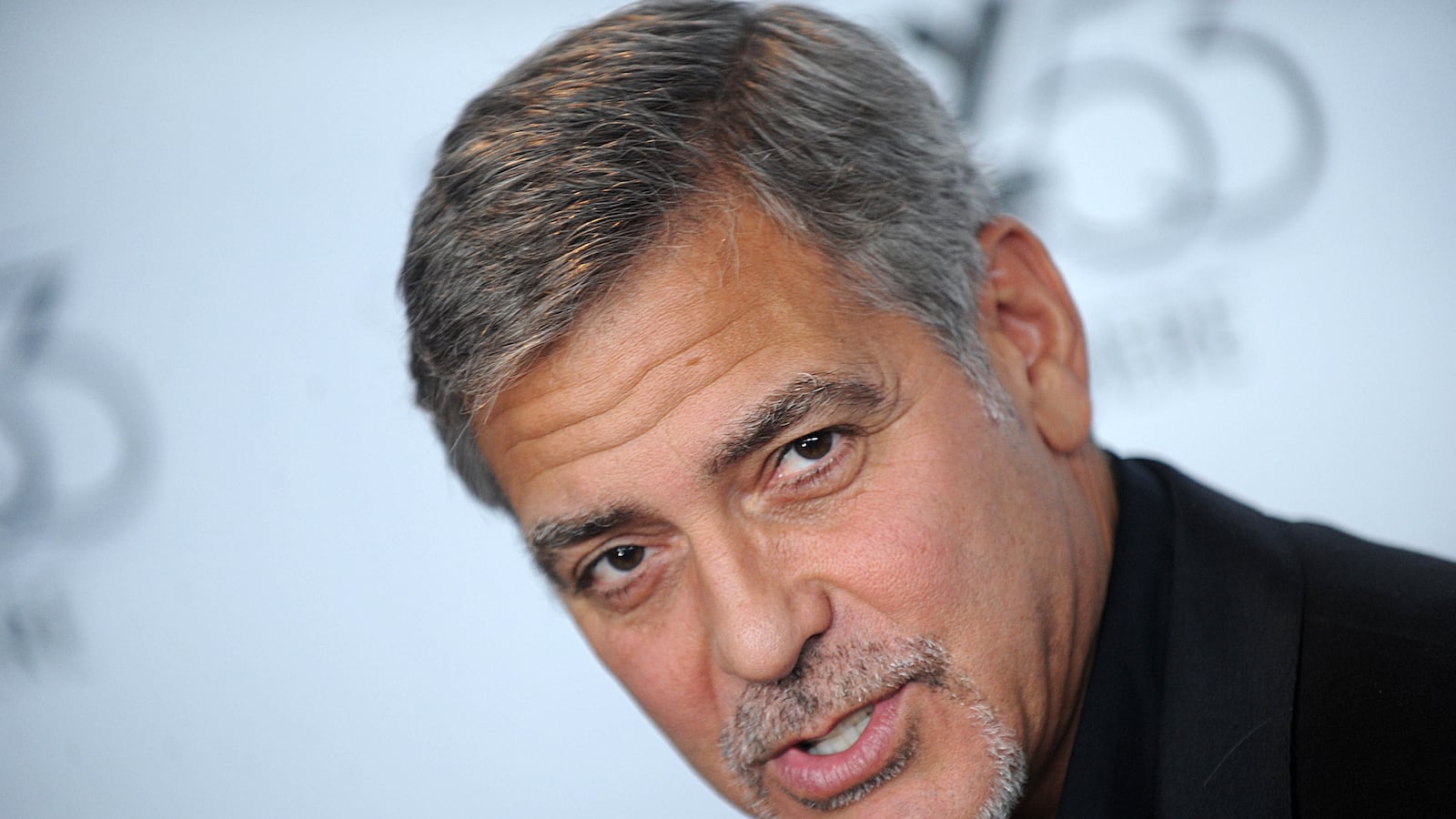

George Clooney, it’s your choice, obviously, but we’d be very happy if you aged before us on camera, mainly because you look fantastic and you’re an engaging screen presence.

But mostly because, if you—sane, clever, intelligent George Clooney—start buying the ageist baloney that you can be too “old” to act, then that whooshing sound you just heard was the hope rushing from the room for the rest of us.

Clooney told the BBC: “I think nobody really wants us to see anybody really age. You know, it’s a very unforgiving thing, the camera is, and so aging becomes something that you try to do less and less on screen. You try to pick the films that work best for you, and as you age they become less and less.”

Directing, Clooney (a not-that-old 54) added, “is my great love. I do enjoy it a lot. I’ve had really great success and I’ve had some not-so successful films…but what I’ll say is it’s really fun. As you age on screen you get to that point where you really understand that you can’t stay in front of the camera your whole life, and so it’s much more fun and it’s infinitely more creative to be directing—infinitely more.”

Of course, Clooney is still pin-up worthy, still swoony-handsome. But it seems even he has fallen prey to the Hollywood aging trap. (What crazy hall of mirrors do they operate out there?)

The HD camera may be unforgiving, but people are not—and cinema-goers and TV-watchers spend rather less time fretting about how many wrinkles someone has, compared to the value and worth of the performance they are giving. We admire Clooney too for being proudly political and socially engaged, today calling out Donald Trump as a “xenophobic fascist” in an interview with the Guardian.

When I interviewed Clooney for the London Times (he is as charming, intelligent and handsome in real life as any fan would hope), it was just as he was nominated for an Oscar and Bafta for The Descendants, in which his character tends to a critically ill wife who has cheated on him. He called it his “midlife movie.”

“Getting older on screen is not for pussies or the faint of heart,” he told me. “People go on about your gray hair, your eyes starting to sag.”

I asked if he ever had plastic surgery. “No, nothing.” Would he? “Never. We’re guys, we have the insane great luck of being able to go bald, fat, wrinkled and gray and no one says, ‘You can’t do that, you can’t be a leading man.’ Why would any male actor cut around their eyes? Why would you ever f**k with your face?”

Turning 50 “wasn’t a big year,” although it marked an acceptance of becoming “a character actor. If you don’t, the audience you’re desperate to hold on to will go, ‘This is silly.’ If you fall in love with the idea of how you were in 1998 you will be greatly disappointed by how you are in 2012.”

Like his character in The Descendants, “I’m the kind of guy who could just sit in a room, watch TV and let days go by.”

But he has not. The directing bug has bit, and that has coincided with this bout of aging anxiety.

Yet ageing on camera, and playing roles featuring people of advancing age can be immensely enriching for both actor and audience: think Jeffrey Tambor in Transparent, Charlotte Rampling in 45 Years, and Meryl Streep in anything.

We like to watch older people on screen in searching, emotional roles. Their age may be immaterial to the part or central, but their age— specifically age—confers a watchability on those faces. We want to see those lines, we don’t shy from them, we don’t mock them. Indeed, you might posit that accepting them helps us accept our own.

The parts for older actors and actresses are increasing as the population itself ages. It doesn’t want just superhero movies and Divergent Part X’s. It wants variety, and even in the most blockbuster-y superhero or action movies, older faces are welcome. Even a youth audience is not all-consumingly in thrall to youth.

Streep, and her command and brilliance, is an instructive example because she and other actresses at varying ends of the “older” spectrum—from Julianne Moore to Dame Maggie Smith, Cicely Tyson, and Vanessa Redgrave—show that a woman’s acting life can be long; that more and more roles do exist for older actresses; roles that the public will pay to watch these women to perform. And so it is with as equally a diverse group of men, including Forest Whitaker, Michael Keaton, and Jeff Daniels.

Just as absurdly as it has been taken on by Clooney, on-screen aging anxieties are ascribed to actresses rather than actors. What his words show is that today’s men are just as aware, and wary of the effects of aging—and willing to vocalize them—as women.

And yet Clooney is wrong, not just about himself, but also us. “I think nobody really wants us to see anybody really age,” he says.

Yet, for this viewer at least, watching the aging of an actor deepens the relationship the audience has with that actor, not only because it opens up a variety of new roles, but also because the audience is aging too. Aging can be one of the great shared empathies.

If we all share one experience, it is the progression of time, and that progression’s effects on us, for good and ill. Being older on screen or stage can be anchoring—a canny paterfamilias, a wise dispenser of advice—or disruptive and transfixing, like King Lear and his many fictional descendants.

The strange thing is, Clooney was previously thought of as emblematic of aging sexily, and gracefully: the ultimate silver fox. In the interview with the BBC, he looks as good as he always does, and yet what his words reveal is that despite all the blandishments his looks have earned him, all the flattery and hornily-fainting editorials, he himself, like many of us, sees his face in the mirror differently.

And in his determined bid to not look at himself, Clooney is perhaps like a lot of those watching him on screen, staring at ourselves, measuring ourselves, and judging ourselves in an aging, and body-obsessed, culture.

Also in 2012, Clooney told me: “Every time you see a retired person they seem to play golf and die. I have no interest in that shit. This is fun, but I’m terrified of the moment when you’re the guy who goes to the studio and says, ‘Hey, I’ve got this idea,’ and they’re like, ‘Thanks for stopping by,’ and you walk out and they roll their eyes. The easiest way to become irrelevant is to stop. You have to reinvent yourself.”

This may explain his segue to direction over acting.

When he made Syriana, Clooney injured his neck, leaving him in so much pain he contemplated suicide.

He told me: “I fear death like most people, but I’m a realist: I thought, ‘Well, you can die young or live long enough to watch your friends die.’ It doesn’t end well whatever. Having understood that—and that is the driving force of my life—it made me go, ‘You must attack life and not get dragged into things that mean nothing. If you knew you had a week left, what’s more important—award statuettes or the films you leave behind? Is what people pigeonhole you as important? If you sit in Hollywood and get caught up in it, or google yourself, you live in hell.”

Given his own drive, it seems unlikely Clooney will ever reside there. But is the answer to his aging conundrum to cancel himself out of an on-camera life completely? Of course not. Surely he should continue both acting and directing, and simply choose the acting roles carefully. But he should defy ageism, not give into it.

Hollywood is already full of frozen faces that don’t look as young as the surgeon promised their wearers. Clooney should not help the onward march of these smooth-skinned, shiny robot foreheads to prevail, but rather stay on screen, stay in the game, and stay charming us. We’ll pay to see it.