No question, the doctor was looking at my shirt pocket. Did he see the tiny hole? If he did, that small opening presented a major problem. Did he recognize me?

I was wearing thick glasses instead of my usual contacts. My on-air hair had never looked so disheveled. Even my friends wouldn’t recognize me without my usual television makeup. I was undercover and in disguise. At least I thought so. But the doctor’s wandering eyes were making me nervous.

A source had told us this guy was lying to patients about his history as an obstetrician. He’d been hammered with malpractice suits, and lost, time after time after time. And the state had suspended his license. But state laws at the time didn’t require him to tell that to patients. Back then, to find a doctor’s legal history, a patient would have to search court files, which in some cases were sealed.

We’d asked Massachusetts state officials, “How are potential patients supposed to find out a doctor’s legal record?” And we were told, “Ask the doctor. They’re supposed to tell you.”

But would they? Or would they lie?

There’s a principle called the Hawthorne Effect, the history of which is more lore than reality, but the theory is that simply the act of observing a situation changes it. Any teenager knows one version of that is true: If you fear your mom is watching, your behavior will be markedly different. Here’s the journalism corollary: If a subject knows a reporter is asking the question, they’ll respond with a different answer than they would to someone who isn’t.

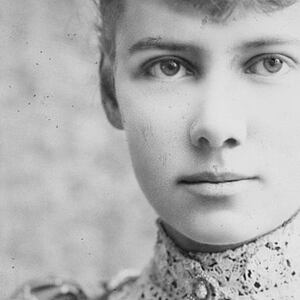

The brave and iconic Nellie Bly, working for Joseph Pulitzer’s The New York World, suspected brutality and violence against the women in the “Women’s Lunatic Asylum” in Blackwell, New York. To get the story—in 1887—she pretended to be insane and got herself admitted. She lived as a mental patient in the asylum’s terrifyingly miserable conditions for ten days, until The World got her out. She then sealed her career and reputation with her shocking expose.

If Nellie Bly had shown up at the asylum and presented herself at a reporter, would the heartless and corrupt administration there have politely shown her around? Taken her to the dank back cells of the place, let her see the haunted-eyed women in their filth and rags? Nellie knew the answer: The only way to see reality was not to let them know she was looking.

So, for my assignment, in that present-day Boston, I wondered: Would a doctor tell a patient about their malpractice history?

Like Nellie, I knew I couldn’t find out unless I was a patient.

Our TV news story for a major Boston network, tentatively titled “Private Practices,” would explore why doctors’ legal histories weren’t easier to check. Whether that truth would matter to a patient would be their own decision. But we thought the public had a right to know—and that patients should be able to make decisions based on all the facts.

Accompanied by my “husband”—actually my producer—we’d gotten an appointment with a certain doctor, offering ourselves as a couple exploring the possibility of pregnancy.

What we hoped the doctor didn’t know: that the tiny cigarette burn hole on the front pocket of my rumpled navy linen shirt was actually the opening for a tiny camera lens. (We called it button-cam.) A thin wire snaked down from behind it, under my shirt, and tucked under my belt. Attached to that, and zipped into my goofy-looking fanny pack, was the guts of the hidden camera. I hoped the lens in my chest was pointed at his face. I hoped the tape was rolling in my pack. And I sure hoped Doctor X didn’t realize it.

We knew this doctor had a history of malpractice. And not just the one or two cases some doctors have. This guy, he had more than a few. Bad ones. And lost. Big time. Would he tell us? If we came right out and asked? Remember—he was supposed to. State medical officials said so.

And the intensity of the moment was not simply about what answer we’d get.

When you’re undercover and carrying a hidden camera, there’s no room for error. Would this be the time I got caught?

I silently chanted my mantra. Rule one of undercover shooting: The target doesn’t know. The target doesn’t know. The last thing this guy figured was that the middle-aged couple sitting in his low-rent office were actually a television reporter and producer posing as husband and wife. But even though what we were doing was perfectly legal, and for the benefit of the public, and on the side of the good guys—when you’re on the reporter side of the camera, there’s never a moment when you feel certain it will work. Every moment is stomach-twistingly tense.

In Massachusetts, the law does not allow for secret taping of audio. So, the microphone was turned off. But silent video? That’s fine.

And in television, if it’s not on video, it didn’t happen. And we had to get the video.

He kept looking at my chest. I ignored it. Eventually, as our chat drew to a close, I asked him the big question: Have you ever had a malpractice case against you? “No, certainly not,” he told us, shaking his head, “absolutely not.”

I knew you wouldn’t have to be a lip-reader to translate that empathic no. And the added visual of the headshake made his silent answer—a lie—even more clear.

Making sure, I asked again. “Oh, not any? Never? At all?” This time his denial–his lie—was even more visual and dramatic.

Thanks so much, we said. We finished the interview. I backed out of the room, getting video of him at his desk. Bingo. He’d kept his secret past a secret. And we got outta there. Our story won an Emmy. And as a result, state law was changed to require Massachusetts doctors to list their malpractice cases on state-mandated public profiles.

A few months before, with a fake ponytail sticking out from under a Red Sox cap and wearing a dowdy dress, I had posed as a potential victim at what a source had divulged was a recruitment meeting for a cult organization. A shady group was luring vulnerable young women into handing over their money in return for some “salvation.”

This time, our fancy button-cam was in the engineers shop for repairs. But the cult meeting was that night. It was now or never. So, I resorted to a more-old-fashioned method. And by old-fashioned, I mean risky.

I’d cut a quarter-sized hole in the side of an old purse, and tucked a regular Hi-8 camera inside, using black electrician’s tape to hold the lens against the hole. Then I tied a flowery silk scarf over the strap of the purse. When the scarf was down, the lens was covered. And I’d only have pictures of the scarf. When I moved the scarf aside, the lens would show, and I could get pictures of the cult meeting. Of course, at that point, the lens was also pretty visible.

It was as good as it was going to get.

Out in the parking lot, I pushed the camera’s record button. I adjusted the scarf (and my phony persona), and walked through the door, pretending I was just another guest.

Standing in the back of the room, I assessed the situation, then moved the scarf aside. Rolling with video.

Smiling and soft-spoken girls, looking just out of college, circulated quietly, offering lemonade. One caught my eye from across the room, and I saw her decide to approach me. Closer. Closer. Too close. The scarf went over the lens.

I took the lemonade. I didn’t drink it. I was trying to look like someone who might be vulnerable to being brainwashed, but not too vulnerable. I was a little apprehensive about the lemonade.

The music was loud. The lights were bright. A woman stepped to a podium at the front of the room. I knew my camera was still rolling. I knew the tape inside was only 30 minutes long. Thirty minutes of scarf was not going to cut it.

I moved the scarf aside.

And then—I felt a tap in my shoulder.

I turned. A man in a suit looked at me through narrowed eyes.

“What’s in your purse?” he asked.

In television, you’re only as good as your last story. And, I remember, I briefly wondered if this would be the last story I ever did.

But rule number two of undercover shooting: The best defense is a good offense.

Scarf down. I turned on the charm. I giggled, and in a non-Hank voice chirped, “Yes, my mother always tells me I carry too much stuff.” He looked at me, not quite convinced.

I moved to another tactic. “You’re making me uncomfortable,” I said, making my voice edgier. “Are you supposed to be asking women that?”

He turned on his heel. Outta there. And then I high tailed it for the door. Outta there.

The story was a blockbuster. And the cult church is no more.

I remember the specific moment I knew I was meant to be a reporter.

We were interviewing the head of the water department in a coastal Massachusetts town. We had been leaked some information that there might be carcinogens called trihalomethanes (THMs) in the town’s water.

Camera rolling—this time not hidden—I asked him, “Are there trihalomethanes in the water in your town?”

He said, looking right at me, “We have no evidence of THMs in our town.”

Even now, writing this, I remember feeling the gears in my brain start to turn. I bet this was in… 1981.

I had started in radio in 1970 (and got my job without one shred of journalism experience after I informed the news director that the station’s license was up for renewal at the FCC and they had no women reporters). I fell in love with storytelling, and went on into television in 1975. My first big story? Covering the push for the swine flu vaccine.

That’s when I began to realize that my stories had power. That I could ask any question I wanted, and someone would have to answer, and people’s lives would change as a result of my curiosity. I remember gasping with the responsibility of it.

I remembered, too, that as a kid, whenever I would ask my mother a question, she would say, “Why don’t you go and find out for yourself?” And I loved proving to her that I could find the answers on my own.

So back to the water department.

“We have no evidence of trihalomethanes in our town water,” he said.

I looked him square in the eye. The gears in my brain had clicked into place. “Have you ever looked?”

There was a beat of silence, and then another one.

“No,” he said.

“So you’ve never tested.”

“No.”

“So you have no idea what’s in your water.”

“No,” he said.

I knew it would be unseemly for me to stand up and point at him and say gotcha. So I just said thank you. And it’s those moments—the change-the-world, make-a-difference moments—that keep me hungry for the next story.

But there’s one story that a television reporter like me cannot tell. And that is how I felt about going after it. Whether I was enthusiastic or terrified, whether I’d been assigned the story by some arm-twisting editor or whether I’d enterprised it on my own. No viewer knows that I shot 5 hours of video tape, but only could use two minutes and thirty seconds of it. What did I decide to leave out? Why? How did I decide what was true? They’d never know whether I was sympathetic to one side or the other. How I dreamed about the story, and fretted over it, how I chose every single word, and every single sound bite.

Because here’s the reality: In a solid piece of journalism, the reporter as a human being is always undercover.

The reporter’s philosophy is buried in the story—their fears, and their goals, their personalities, and their emotions. In a solid piece of journalism, the reader will never know the passion or complications or even the behind the scenes pressures that affect which words the viewers will hear and which pictures they’ll see.

But now I’m a novelist and in fiction, I don’t have to go undercover anymore.

When I’m at my writing desk, people can say what I want them to say. The characters will do what I want them to do. The good guys will win, and the villains will get what’s coming to them, and in the end—reliably, because I made it so—there will be justice. And the world--a fictional world of course—will change.

Writing fiction has let me come out from undercover.