In the wake of the murderous rampage at Orlando’s gay nightclub Pulse—the nation’s worst mass shooting ever—it’s inevitable that politicians would respond by calling for tighter gun-control laws. As Hillary Clinton put it on the Today show, “We need to get these weapons of war off the streets. We had an assault weapons ban, it expired, and we need to reinstate it.”

Inevitable, yes, and understandable too. And totally besides the point. Laws addressing criminal behavior aren’t going to prevent terrorism.

By every account, the shooter Omar Mateen was ideologically and theologically motivated—he called 911 to pledge his loyalty to the leader of the Islamic State before starting his homophobic attack—and thus unlikely to be deterred by legal prohibitions. His father told NBC News that his son was disgusted by the sight of two men kissing, his ex-wife said that he had beaten her, and his former workmates called him “toxic” and aggrieved by “women, race, and religion.” Exactly how reducing law-abiding citizens’ legal access to weapons will stop a jihadist bent on a suicide mission or even a garden-variety nut job from a rampage is something politicians don’t pause to explain, especially since they never seriously suggest pulling a significant portion of the 357 million guns in America out of circulation.

More specifically, the assault weapons ban that Clinton cites was in effect from 1994 until 2003 and had no discernible impact on gun violence. A 2004 study (PDF) commissioned by the Department of Justice found that gun crime did decrease during the ban, which outlawed 18 types of rifles and large-capacity magazines (LCMs). But because assault weapons—whether rifles or pistols—were so rarely used in shootings, the researchers concluded that "we cannot clearly credit the ban with any of the nation’s recent drop in gun violence.” The authors argued that if the assault weapons ban were reinstated, its “effects on gun violence are likely to be small at best and perhaps too small for reliable measurement.”

As telling, it’s not immediately clear whether one of Mateen’s weapons—an AR-15 rifle, among the most popular of its type in the country—would have been covered by the ban. Depending on a series of mostly cosmetic differences, some AR-15s were banned and others weren’t.

Nor is there reason to believe that mass shootings are on the rise over the past 30 years or so. Writing in the wake of last fall’s shooting at a community college in Oregon, Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox, widely regarded as the authority on mass shootings, say there is no clear pattern. “Using the widely accepted definition of at least four killed,” he wrote in USA Today, “the Congressional Research Service found that there are, on average, just over 20 incidents annually. More important, the increase in cases, if there was one at all, is negligible. Indeed, the only genuine increase is in hype and hysteria.”

In fact, one of the most unremarked-upon developments of the past two decades is a massive, nation-wide reduction in violent crime, especially gun-related violent crime. In 1993, according to Pew Research figures, there were seven gun homicides per 100,000 people. In 2014, the latest year for which there is full data, the rate was 3.4 percent, a decline of nearly 50 percent. “Nonfatal violent firearm crime victimizations dropped even over the same time frame, from 725 per 100,000 to 175 per 100,000.

The result of such a decline is that crime is no longer an issue in national politics the way it was from at least the mid-1960s through the mid-1990s. In the 1968 presidential campaign, Richard Nixon capitalized on rising crime rates, riots, and anti-war protests by running commercials that promised an end to “domestic violence” and that “the wave of crime is not going to be the wave of the future in America.” George Wallace similarly pledged to “make it possible for you and your families to walk the streets of our cities in safety.” Such appeals continued for decades, through the infamous Willie Horton ad in 1988 and Bill Clinton’s 1992 spot bragging that he and Al Gore “sent a strong signal to criminals by supporting the death penalty.”

By the mid-1990s—at the exact moment most criminologists (including Fox) predicted a historic surge in lawlessness by “super-predators”—crime was off the table as an issue. The reasons for the decline in crime are multiple and not all are unalloyed goods. The reduction of lead in the environment, for instance, may explain some reduction in anti-social behavior and so does an increase not just in the number of police but the use of computer-assisted policing. But it’s also true that massively heightened levels of incarceration and aggressive methods that violated civil liberties such as “stop and frisk” played a significant role.

Apart from its gruesome body count, the Orlando shooting is particularly heinous because it targeted gays, a group that until recently was denied legal and cultural support from “normal” society and as likely as not to be harassed as helped by law enforcement. But it shouldn’t be used to effect policy changes that will do nothing to prevent the terroristic violence that Mateen perpetrated. Indeed, even the post-9/11 protocols that are in place to monitor likely terrorists failed in this instance, as Mateen was investigated at least twice by the FBI based on tips from co-workers, his background, and his behavior.

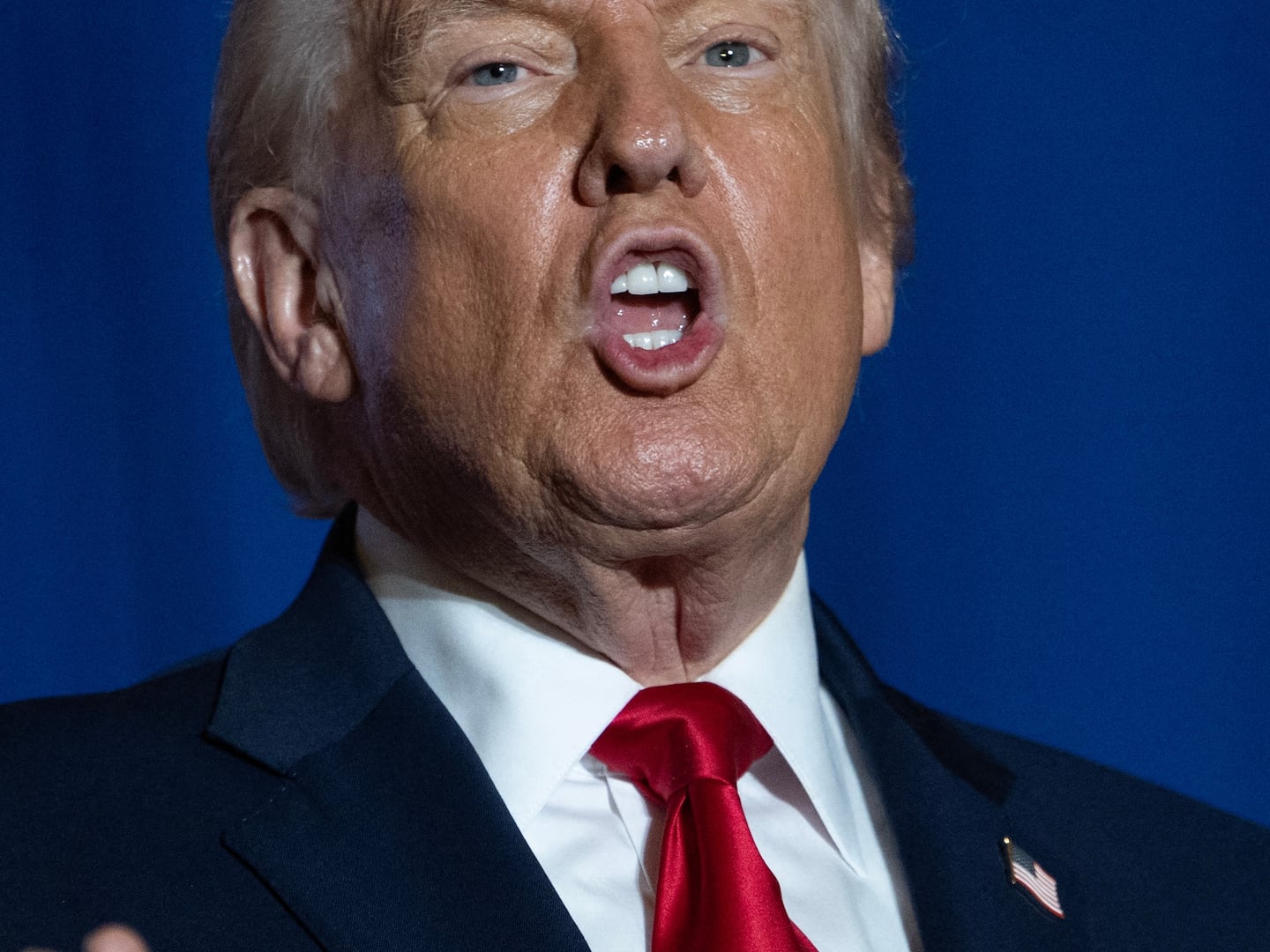

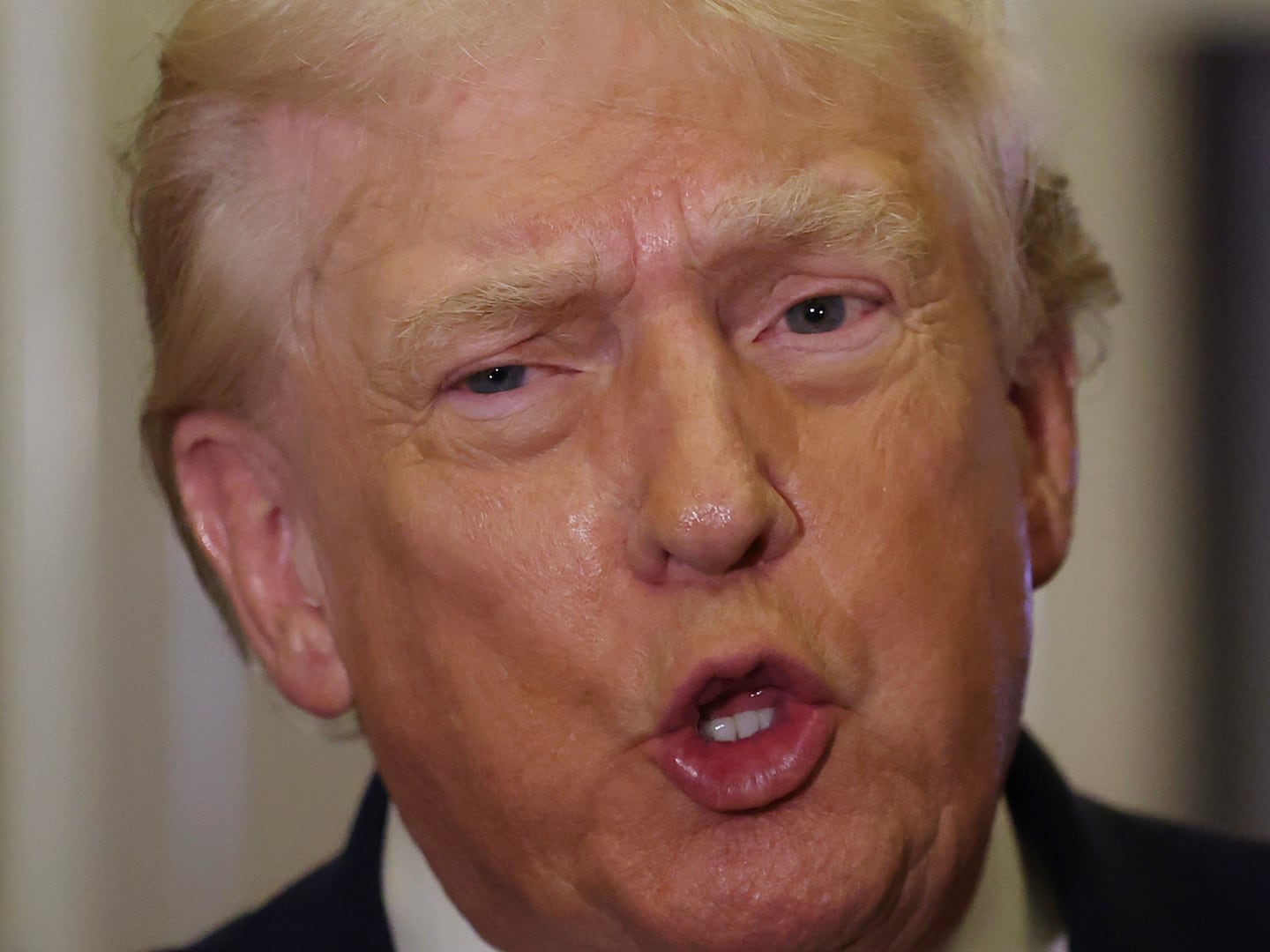

Where Hillary Clinton has called for increased gun control, of course, Donald Trump has called for an equally unconstitutional and impossible ban, this one on Muslims and Middle Easterners. The Orlando shooting presents politicians as both crusading and cynical, as they can only offer up solutions that will do nothing but inflame the pre-existing prejudices of their constituents.

The one thing that they—and perhaps us, too—cannot countenance, especially in an era when violence is at a low ebb, is that evil cannot be fully exterminated from our lives.