On a picturesque peninsula of one of Hawaii’s smallest islands are the remnants of one of history’s most horrific medical sequesters.

Kalaupapa, on the island of Molokai, is Hawaii’s leprosy colony, where 8,000 people were sent into exile over the course of a century.

Six of these patients still live sequestered, out of the 16 total patients who are still alive. They range in age from 73 to 92.

Soon, the last memory holders of the peninsula’s dark history will be gone.

In the early 1800s, Hawaii was being ravaged by diseases brought in by foreign merchant ships. Venereal disease killed 10,000 over two decades. Typhoid killed 5,000.

Over the course of 1853, smallpox left 15,000 dead, according to the book The Colony, a history of Kalaupapa. A decade later, a new disease was being called “Mai Pake,” according to a doctor at the time, who diagnosed it as “the genuine Oriental leprosy.”

The state decided a policy of mandatory quarantine was the only way to stem this disease, which was falsely considered highly infectious.

The isolation was made by decree of King Kamehameha V, who issued an “Act of Prevent the Spread of Leprosy” in 1865.

Thousands of leprosy patients were banished to the 8,725-acre area. This forceful seclusion prevailed until 1969, when it was finally removed from the law books.

The colony’s first patient was J.D. Kahauliko, who arrived on January 6, 1866 with 11 other sufferers. In those early days, the government made no provision of food for the community, expecting its new inhabitants to farm the land. They shared blankets and rationed water in makeshift shelters.

The colony grew into a community, and there were thousands of marriages.

But the patients were still considered pariahs, stemming from widely held misconceptions about the disease.

Children born to patients held in Kalaupapa were immediately separated from their mothers and given to adoptive families. Many would grow up without knowing their past.

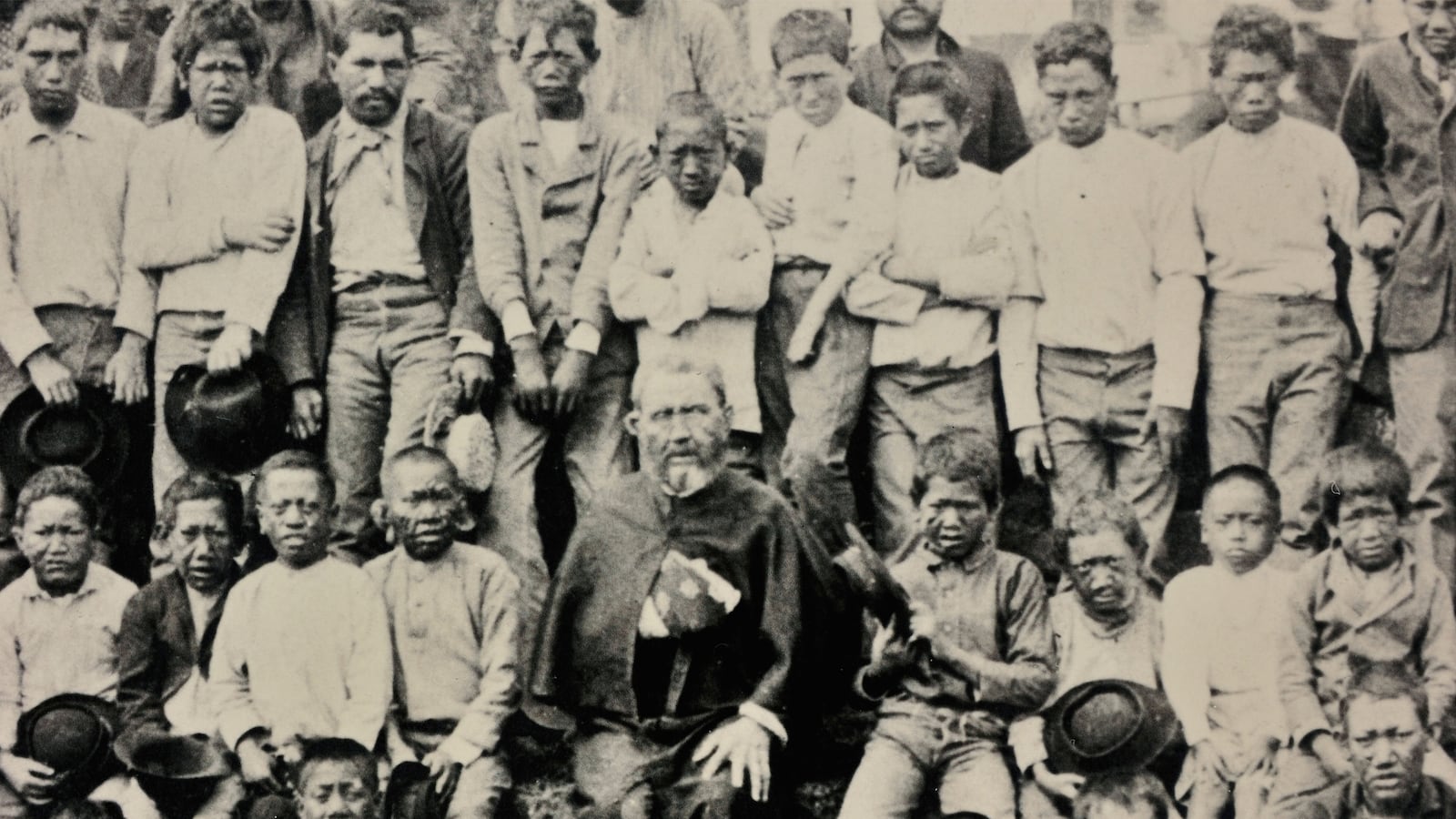

One of the site’s early inhabitants was Father Damien, a Catholic priest who ended up contracting the disease and dying there after serving the community for 16 years. He and another caretaker, Sister Marianna Cope, were both later sainted, making the island a pilgrimage site for religious visitors.

According to The Colony, the sequester was the longest and deadliest medical segregation in U.S. history. The area today is scattered with cemeteries that were the final resting place of the thousands exiled there.

In 1980, Kalaupapa was turned into a National Historic Park. But access has remained limited, with only 100 visitors are allowed in the park per day.

The only way to get to the isolated peninsula is by boat or nine-passenger plane, and tourists come on the backs of mules that navigate the cliffside paths.

Today, around 40 federal park employees along with a team of health professionals live around Kalaupapa.

There’s little to do in the neighborhood, which doesn’t have restaurants or markets or schools. There are three churches. Food is delivered by plane, and large shipments of big-ticket items like cars come in once a year.

Once its last residents die, the government has to figure out what to do with the land.

The National Park Service has been planning what to do with the land since 2009 and boiled down to four proposals that would either open the area more or require special passes.

Many are concerned about what a trample of tourists would do to the environment, and fear that the area’s history will fall to the wayside.

The cemeteries are in poor shape, with only 1,300 identifiable tombstones, and at least 2,000 unmarked graves.

Regardless, there is a plan to build a memorial to the 8,000 patients who once lived there.

In 2009, President Obama signed legislation to build a monument listing the names of everyone who was sent to the island.

The effort is being led by an organization called Ka’Ohana O Kalaupapa, which was formed in 2003 to honor the memory of the colony’s residents. In 2010, it held the first-ever gathering for descendants of patients at Kalaupapa on the island.

Even though they’ve been free to leave for half a century, the remaining residents prefer life in seclusion from the rest of the world.

Leprosy is now known as Hansen’s disease, and though it is now easily treated there is still no vaccine. The disease is still widely misunderstood and its victims stigmatized.

"One of the worst things about having had this disease is that even after you're cured, society will not let you heal because of 'L' word," a patient named Makia Malo told the Associated Press in 2003. "People don't know how hurtful and wrong that term is."

Some of Kalaupapa’s last patients want the colony to open up, so outsiders can learn about their lives before the last witnesses are gone.

"Come when we alive. No come when we all dead," said Clarence "Boogie" Kahilihiwa, speaking in Pidgin to The Associated Press earlier this year. The 74-year-old has lived there since 1959.

"Before it was shame, they didn't want to talk to us," he said. "But now, everybody wants to reach out."