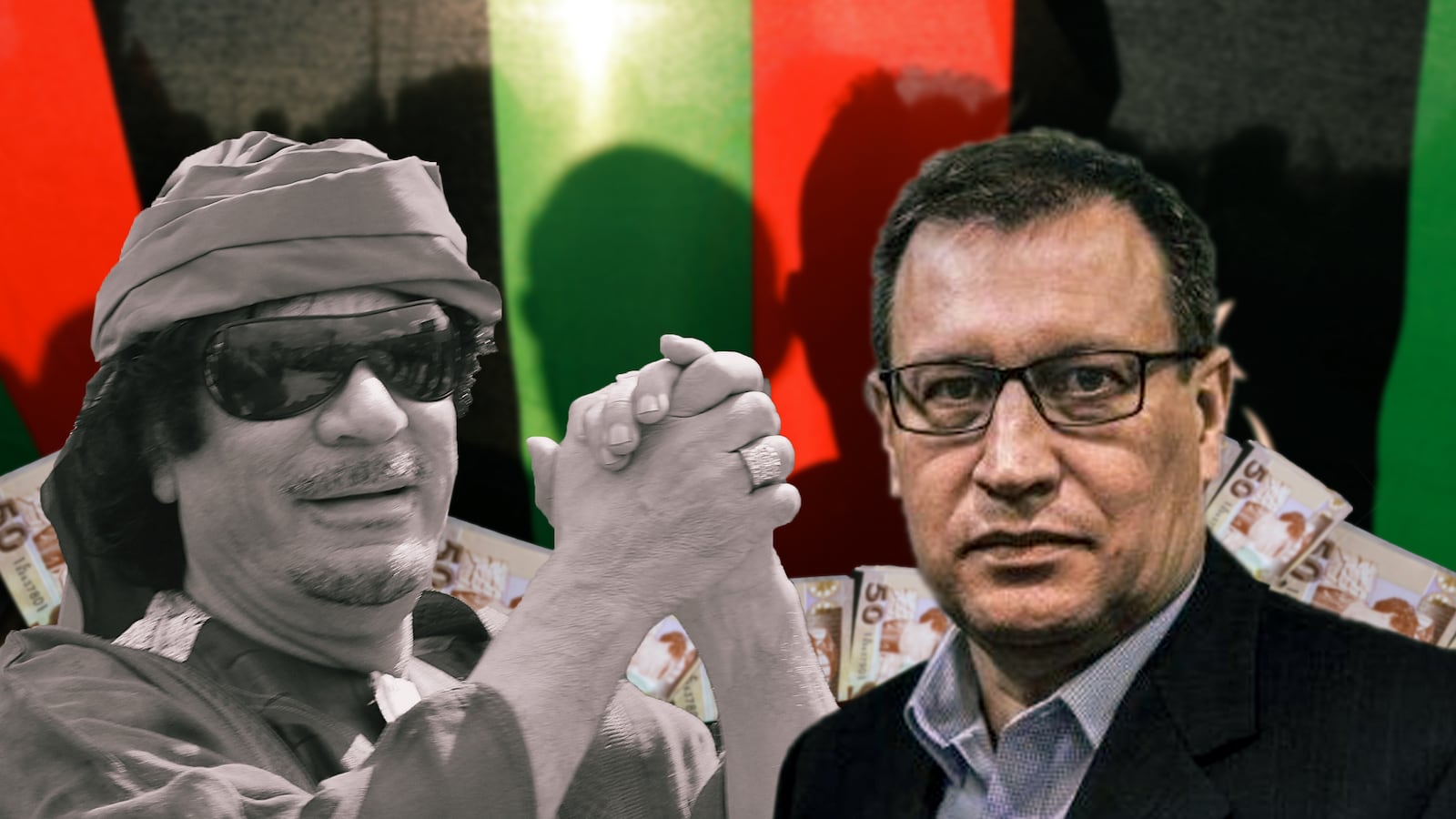

In August 2014, Erik Iskander Goaied formed a company to locate what he claims is $150 billion or more in U.S. currency, gold, diamonds, and other assets. This is the loot that Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi had squirreled away outside of Libya before he was deposed in 2011. Goaied claims to have a contract with the Libyan government that lets him keep 10 percent of what he finds, which means that if he locates even a fraction of the money he insists is sitting in bank accounts, as well as warehouses, around the world, he will instantly become a billionaire.

Lots of people have been looking for this money. The Libyan government has tried for years to repatriate assets Gaddafi either deposited or laundered outside the country. Investigators say they think they’ve found much of it already in banks in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany, and those funds have been frozen.

Goaied, for his part, insists he found $12.5 billion of Gaddafi’s cash sitting on pallets in a Johannesburg airplane hangar a few years ago. And that, Goaied says, is just a taste of what he can find and bring home to a country that’s been wracked by civil war and decades of Gaddafi’s corruption. His finder’s fee will be a comparative pittance.

Libya sorely needs the cash. The country is arguably a failed state, with rival factions in the capital, Tripoli, and the eastern city of Tobruk vying for control. Whoever ends up running Libya will need billions to rebuild the country. If Goaied were legitimate, he could be Libya’s next hero.

And legitimacy is exactly what Goaied wants. Three months after he started his company, called the Washington African Consulting Group, Goaied registered with the Justice Department as an agent of the “Libyan Government Prime Minister’s Office,” claiming that he’s working in the United States trying to help the people of Libya recover what’s rightly theirs. (He first came to my attention when I was reviewing recent registrations, which are publicly disclosed. I contacted Goaied through his website and he agreed to meet with me.)

Under a 1938 law meant to weed out corrupt influence, individuals conducting political work on behalf of foreign countries are required to disclose that fact to the government. Registrations like the one Goaied filed are standard operating procedure for thousands of lobbyists, lawyers, spin doctors, and political advisers representing more than 100 countries to the U.S. federal government. To demonstrate his bona fides, Goaied included an 18-page contract between his company and a “National Board” that was set up, he says, to repatriate Gaddafi’s ill-gotten gains, pursuant to an official Libyan government decree.

Misrepresenting oneself to the U.S. government as a foreign agent could trigger prosecution for false claims, punishable by as much as five years in prison. So one assumes that Goaied’s claims are legit. After all, why would he be crazy enough to say he’s working for the Libyan government if he’s really not?

That may be exactly the question he wants you to ask.

Registering with the Justice Department gives Goaied’s loot-hunting an air of credibility and legitimacy— and, arguably, the imprimatur of the U.S. government. Over the past three years, at least three different groups of investigators have tried to find Gaddafi’s money, and each has claimed to have a binding agreement with the Libyan government. But only Goaied has sworn to the U.S. that he’s Libya’s chosen man.

Those assurances helped persuade a powerful Washington lobbyist and political fundraiser, Ben Barnes, to agree to advocate on Goaied’s behalf and try to influence U.S. policies concerning Gaddafi’s assets. And Goaied appears also to have persuaded U.S. officials that he’s the real deal, because his contract and his registration forms are still on file at the Justice Department, in a database of “active” foreign agents.

Maybe they all missed the fact that Libyan officials, as well as the United Nations, have accused Goaied of peddling fake documents to at least three different governments in an effort to stake a claim to the missing billions. The Justice Department documents, the Washington influence man: They’re illegitimate attempts by Goaied to position himself to acquire Gaddafi’s treasures, according to these sources. A scam, in other words.

But if Goaied is indeed a con man, his scheme is one of the more improbable bankshots to riches. And it says a lot about the shadowy scene of foreign influence in Washington that most people never get to see.

“It’s a funny story,” Goaied told me about his work, when we met recently for coffee at a Washington, D.C., hotel.

He wasn’t kidding.

Goaied may be the most unlikely of the Gaddafi loot hunters, who have included former U.S. government officials, Libyan businessmen, and financial investigators working for the United Nations. Soft-spoken, with intense eyes, he says he was born to Tunisian and Swedish parents, is 49 years old, speaks five languages, and has worked as an oil company consultant, a land manager, and a commercial pilot. When I asked him how his past experience had prepared him for his present occupation, he didn’t have a clear answer. But he said he had an extensive network of contacts in South Africa, where he’s done business since the late 1990s. That’s where Goaied claims that up to 80 percent of Gaddafi’s assets are sitting right now.

This is not a completely far-fetched idea. The ties between Libya and South Africa run deep. During the era of apartheid, Libya helped fund South African liberation groups and trained militants with the African National Congress. After Nelson Mandela was freed from prison and became president, he made two official visits to Tripoli. Mandela was one of the few foreign leaders to embrace Gaddafi, and certainly the most esteemed, at a time when much of the world saw the Libyan dictator as a terrorist-abetting pariah with a penchant for garish clothing and European women.

South Africa was also accused of laundering Libyan money for years, according to several experts on illicit financing. And ever since Gaddafi fell, stories have circulated in the press about billions in cash, gold, and diamonds socked away in South Africa bank accounts or in warehouses. One news outfit reported an anonymous allegation that a crew of “ex-special forces” had ferried Gaddafi’s loot out of Tripoli over the course of 62 airplane flights. And the South African media, as well as Libyan authorities, have identified Bashir Saleh, Gaddafi’s former chief of staff and the head of the country’s sovereign wealth fund, as a possible money mule.

Saleh reportedly fled to South Africa after Gaddafi was killed and was seen hobnobbing with government officials and luxuriating in five-star hotels. Interpol has issued a “red notice” for Saleh on behalf of Libyan authorities, who are seeking his arrest on charges of “felony embezzlement of public money” and other financial crimes, as well as abuse of official power.

But when I told several financial investigators that Goaied said a hundred billion dollars or more was sitting in South Africa, their reaction was the same: They laughed.

Gaddafi’s net worth had been reported at around $90 billion when he died. But by the time investigators started looking for his assets, more than $60 billion had already been identified and seized by banks in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

“What we had to find were those assets not recognized by seizures,” said Yaya J. Fanusie, a former CIA economic analyst who worked for Command Global Services, a company that was looking for Gaddafi’s assets a few years ago. The firm hired ex-IRS and Treasury Department officials with years of money-tracking experience and coordinated with officials at the United Nations, which has its own team of experts who’ve been looking for Gaddafi’s money.

There was little in the way of official records and ledgers to go on when Fanusie was on the trail. He and his colleagues conducted interviews looking for names of Gaddafi’s relatives or associates who might have opened foreign accounts or transported assets out of the country.

“We couldn’t just walk into a bank and say, ‘Where’s the Libyan money?’” Fanusie told me. His team estimated that, at most, there was about $9 to $10 billion in assets left to find around the world.

Goaied may have inflated the figure to lure supporters in the United States. Or perhaps he honestly believes all the other loot-hunters are wrong and have overlooked the mammoth sums that are sitting in South Africa. When we met, Goaied insisted that he had official documents that proved the assets exist, and that he will show them to Libyan authorities. He never showed them to me.

It turns out, however, that Goaied has been trying for years to convince a lot of people that he’s telling the truth and using official-looking forms and decrees to do it.

In 2013, Goaied and another faction of loot hunters were in a “mad scramble” for as much as $10 billion in assets, according to City Press, one of South Africa’s largest newspapers. The problem for Goaied: The other guys not only claimed to be the legitimate representitaves of the Libyan government, but have been recognized as such in a United Nations report. Goaied’s rivals were reportedly trying to out him as a fraud. He needed his own way of legitimizing himself.

At the time, Goaied told me, he was running a different company, called Poviwize, and was working with two men described in local reports as arms dealers, Mohamad Tag and Johan Erasmus. The latter man, Erasmus, was implicated in an alleged scheme in which officials accused his company of importing heavy weapons intended for South African special-operations forces, but then selling them to Syria, Sudan, and Kenya. Erasmus denied the charges. But he also told City Press that he and Goaied had met with a South African arms manufacturer and promised to buy weapons for Libya with the recovered assets. Goaied was also an adviser to the company.

In South Africa, Goaied was also putting himself forward as a representative of the National Board, just as he would later do in his filing with the Justice Department. Its official name is a mouthful: the National Board for the Following-Up and Recovering of the Libyan Looted and Disguised Funds. Goaied told me that it was set up by a decision from a “council of ministers,” pursuant to a document called Decree 378, and “confirmed with a letter of the ministry of foreign affairs in 2014 and the attorney general’s office.”

According to the papers Goaied filed in the U.S., one of the three board members is a Mohamed Tag. He appears to be the arms dealer Goaied worked with when he ran Poviwize, according to UN investigators.

So Goaied had attracted some colorful company. But does that make him a fraud? After all, he says he has papers proving he worked for the National Board, set up by decree.

Throughout our meeting, Goaied obsessively returned to the subject of paperwork, contracts, and official documents to prove he is who he claims to be. His insistence reached a bizarre crescendo when Goaied noted that he’s a licensed commercial pilot, and then pulled out his FAA pilot’s license and let me inspect it, as if he presumed I thought he might be lying.

After our meeting, I contacted the Libyan embassy in Washington and asked about the National Board. The spokesman there agreed that it sounds official.

“The National Board by its very title would seem to be a valid government group,” Baker Garrari told me, “but this is not correct.”

It turns out that Libyan officials have been on to to Goaied’s game for quite some time, a fact he (not surprisingly) failed to mention during our meeting.

Garrari said that the National Board “is not a Libyan government agency, and has no authority to make any commitments whatsoever on behalf of [the] Libyan government. The minister of justice of Libya has found the actions of the National Board of Erik Goaied to be fraudulent.”

Investigators from the UN have also determined the board is a fiction, according to their report. Furthermore, they said the official “decree” Goaied claims established the board in the first place is a forgery. The investigators obtained a copy of it in May 2014, just three months before Goaied started his company in the United States. It’s larded with official-sounding references to ministerial decisions, an “award of confidence,” and bears the signatures of the supposed members of the National Board, including Tag. It’s also covered in stamps and seals, including one purporting to bear the name of a consular official from the South African embassy in Tripoli.

The UN investigators said a representative of Poviwize sent this forged document, along with a “memorandum of understanding” between the company and the National Board, via email to the United Kingdom Home Office, stating the company was authorized to deal with Libyan funds inside the U.K.

It’s the same play Goaied is running in the United States. Only now, it’s the Washington African Consulting Group, not Poviwize, that claims to be working with the National Board, dispatched to America to find Gaddafi’s money there.

Garrari, the Libyan embassy spokesman, told me that Goaeid’s company may have registered with the Justice Department “as a proof that the U.S. government has recognized [it] as an authorized agent of Libya for the recovery of looted funds in South Africa. This is wrong.” The embassy conveyed this message in a “diplomatic note” to the Justice Department on April 15, Garrari said.

Marc Raimondi, a spokesman for the Justice Department, said the he couldn’t discuss specific cases regarding registered foreign agents. “I can tell you that in general, when notified that a filing may be fraudulent, we evaluate the claim vs. the applicant and make a decision about how to remedy the matter based on the facts and evidence,” Raimondi said.

As of this week, the filing is still there, more than a month after the Libyans say they told the Justice Department that Goaied is a phony.

I contacted Goaied about the embassy’s claim. He replied, via email, that he was in Libya and didn’t have time to talk at length, but that this was the first he’d heard of it.

And yet, he also saw no reason why the embassy should know what he was up to. The work he was doing was “so sensitive,” Goaied said, that much of it “has been done with a certain strategy to protect the investigators. And no embassies were involved.”

I asked Goaied why the Libyan embassy in the United States, which is the diplomatic authority that U.S. officials and lawmakers recognize, was challenging his claim. He reiterated that his company “has a contract with a Libyan National Board” that “is under the control of the prime minister’s office.” In other words, separate from the embassy. He repeated the claims about the council of ministers’ decision, and the decree. In a follow-up message, I pointed out that the UN had determined the decree is a forgery and that the National Board doesn’t exist. Goaied didn’t reply.

I also called Goaied’s Washington connection, Ben Barnes. Like Goaied, he also registered with the Justice Department in connection with the efforts to find Gaddafi’s money. His contract with Goaied refers to that forged official decree and the National Board. And it says Barnes’s company “will seek to influence United States policies concerning suspended or frozen assets of Libya within the United States and to strengthen the inter-governmental relations between the two nations.” His fee: $50,000 a month.

Barnes is a political and a social fixture in Washington. A protégé of Lyndon Johnson, he was the youngest person ever elected lieutenant governor in Texas and went on to make millions in real estate. Today, he is one of the top fundraisers in Democratic politics. The guest lists of Barnes’s parties at his office in Washington—a townhouse where Teddy Roosevelt once lived—include members of Congress, prominent journalists, and professional athletes.

Barnes’s company signed the contract with Goaied’s firm last August. When I told Barnes the Libyan embassy had disavowed Goaied as of this April, he told me he was still conducting “due diligence” on the loot-hunter. But, Barnes said, neither he nor any member of his firm had contacted anyone in the U.S. government on Goaied’s behalf. Furthermore, Barnes said Goaied hasn’t paid him in six months, and that as far as he’s concerned, their work together is “suspended.”

However, it appears that Goaied has, at least, drafted off Barnes’s social cred in Washington. In November, Goaied was photographed attending the LBJ Liberty Awards Dinner, a soiree for the Johnson presidential library featuring A-list guests such as Representative John Lewis, Admiral William McRaven, and Senator Jack Reed. Barnes was listed as a top sponsor.

While Goaied’s associates in Washington distance themselves from him and the Justice Department tries to verify his credentials, the government of South Africa is investigating his other company, Poviwize, for what the UN describes in its report as “a believed conspiracy to defraud.”

And in December 2014, a month after Goaied registered the Washington African Consulting Group with the Justice Department, it too came onto the UN’s radar. The investigators report they made inquiries and determined the company was peddling those same forged documents that Poviwize had used. And then, they raised the biggest and most-difficult-to-answer question in this whole affair.

“The aim of the company is to identify Libyan assets in the United States, South Africa, and elsewhere,” the investigators wrote. “What it intends to do with them if identified is unclear…”

Just as a loot-hunter can’t walk into a bank and say, “Show me the Libyan money,” he can’t just walk away with anything he actually finds. Once an investigator locates an account, or even a stack of bills in an airplane hangar, he first has to verify through account or serial numbers or some hard evidence that it’s actually a legitimate asset that can be seized. At that point, his essential work is done. Libyan officials would then engage with their counterparts in whatever country the assets reside. The investigator has to wait for the money to be officially repatriated before he ever takes a cut. Even if Goaied did find any cash, the Libyan government would almost certain never agree to share it with him. This is where the finer points of his alleged scheme become opaque to investigators—and to me.

But this much is clear: Goaied is trying to make friends and influence people in Washington. When I met Goaied, I asked him why he was setting up a company in the United States when he was looking for Libyan money mostly in South Africa. He dodged, but said, in essence, that he thought there were people in Washington who could help make his case and speed up the return of Gaddafi’s funds to Libya. It sounds implausible that Goaied would find some magic fixer, even the likes of Ben Barnes, to cut through the layers of bureaucracy one has to go through when recovering stolen funds. But then again, Goaied did manage to convince some ostensibly smart people that he was the Libyans’ hand-picked man, and that there were billions of dollars just waiting for someone to pick them up. So maybe he’s not so crazy after all.

As we finished our meeting in Washington and were getting ready to leave the hotel, Goaied told me that he loved the city, and that after his work was complete, he wanted to move here. He pointed to a traffic light on the street corner.

“Here, if I cross the street against the light and the police see me, I get a fine,” he said. “In Libya, everyone crosses when they want.” Washington was better than Libya, he said. The rules here are much clearer.

“I’m very good at following all rules,” he said.

Or making them up. Goaied has a funny story, all right. And at least for now, he's sticking to it.