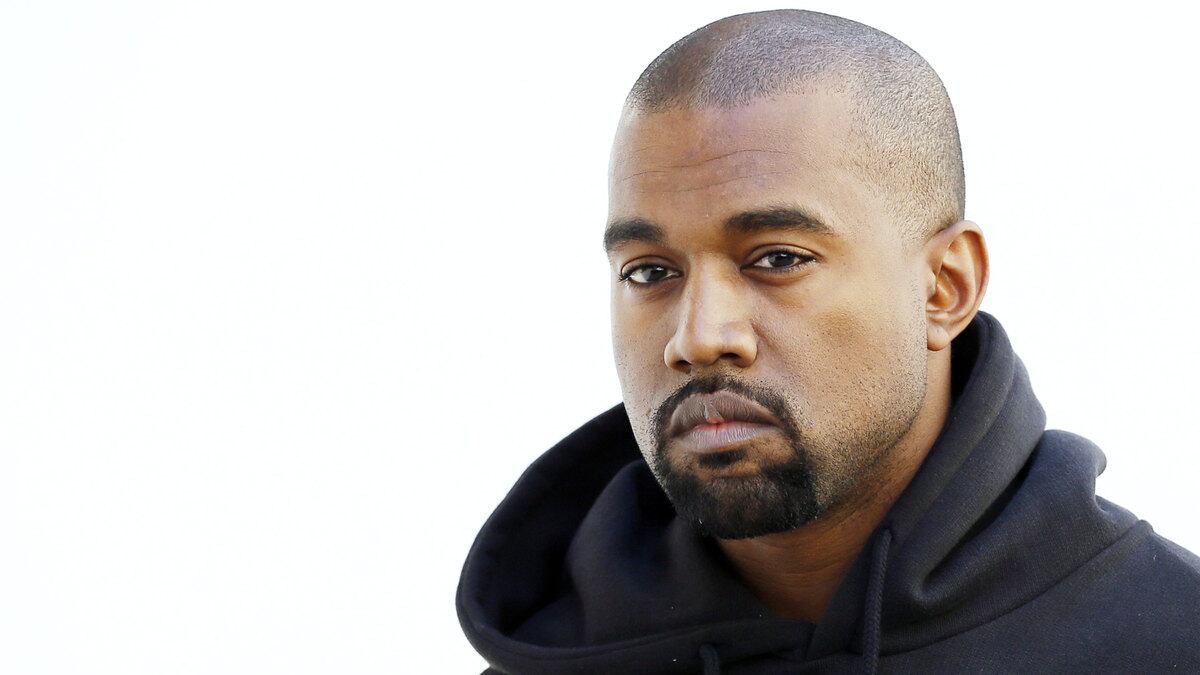

Kanye West lost all credibility for me when he began selling merchandise emblazoned with the Confederate flag back in 2013, but buried within his ramblings about a theoretical 2020 presidential platform is a particularly insidious and dangerous conceit that’s gained some cachet in parts of the Black community: anti-vaccine paranoia.

“It’s so many of our children that are being vaccinated and paralyzed… So when they say the way we’re going to fix Covid is with a vaccine, I’m extremely cautious. That’s the mark of the beast,” he told Forbes, in a pretty irresponsible bit of journalism. “They want to put chips inside of us, they want to do all kinds of things to make it where we can’t cross the gates of heaven.”

If you heard a disheveled, disoriented person shouting this kind of rhetoric on a sidewalk you would likely give them a wide berth, but the anti-vaccination movement has been spreading, like a virus, as celebrities, thought leaders and influencers have hitched themselves to this deeply problematic cause and after Donald Trump had trumpeted claims about vaccines leading to autism.

These politics of paranoia are considerably more complicated within the Black community, where those with even a cursory knowledge of their own history are well aware of the decades-long, unconscionable experiments at Tuskegee University, where Black men were, unbeknownst to them, systematically left to suffer from the effects of syphilis by the Public Health Service, leading to the deaths of hundreds. Then there’s the story of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were harvested in the 1950s without her consent, leading to groundbreaking medical research while leaving her family uncompensated and in the dark for decades.

Not unlike the 1921 race massacre in Tulsa, these stories are another chapter of America’s past that the nation has never reckoned with, inhuman and inexcusable acts with repercussions that are still felt to this day and that have sown deep distrust within many parts of the Black community.

And yet the need for a coronavirus vaccine, especially in communities of color, can not be overstated. As this unforgiving virus has continued to plague this country, one constant has been the disproportionate impact it has had on Black and brown communities. According to a recent New York Times investigative report, Latino and Black Americans are three times as likely to get infected with COVID-19 and are nearly twice as likely to die from the disease.

Racists have used this disparity as a cudgel to drive home heinous stereotypes about people of color. One Republican lawmaker had the audacity to claim in public that people of color don’t wash their hands as well as others, while others have trafficked in misinformation about alleged genetic differences in how the virus affects different racial groups. It doesn’t—the coronavirus is colorblind.

Naturally, these theories conveniently overlook historically inadequate medical care, coverage and access. They choose not to factor in economic conditions which often can lead to overcrowded households where the virus can spread easily or the fact that Black and brown people make up a disproportionate number of frontline workers, who are in high-risk roles that so many people take for granted.

Perhaps Kanye West, a privileged celebrity who has not been shy about the fact that he does not read books, is ignorant about how the coronavirus has spread (although he purportedly had the virus himself at one point) and why a vaccine is the best bet to curtail it.

And those who are fearful of what his supposed 2020 candidacy could lead to should take comfort in the fact that he does not have anything resembling a natural constituency. Besides the fact that he has shown no sense of urgency about actually getting on any ballots. He has come out as not just anti-vaxx but anti-abortion; he’s previously claimed that "slavery was a choice;" and he hasn’t exactly distanced himself from his previous outspoken support for Donald Trump, who enjoys a 10 percent approval rating among African-Americans, the voting bloc West has been viewed as a potential spoiler for.

That being said, the coronavirus claims are one of the few issues where he doesn’t appear to be marching to the beat of his own drum. Back in March, the musician MIA got in hot water for preemptively stoking fear about an eventual vaccine. Meanwhile, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan has also implored Black people globally to be skeptical about any coming cure for the virus

“I say to my brothers and sisters in Africa… if they come up with a vaccine, be careful,” Farrakhan said in a recent speech “Do not take their medications. We need to call a meeting of our skilled virologists, epidemiologists, and students of biology and chemistry,”

“The virus is a pestilence from heaven,” he added. “The only way to stop it is going to heaven.”

That position offers cold comfort for the thousands of infected Black and brown people who are not interested in dying anytime soon. But what fate awaits people of color who have a justifiable suspicion of the federal government, not just when it comes to vaccines but all things?

Certainly Donald Trump, whose administration has taken great pains to shut down immigration into the United States and whose 2020 campaign has centered on preserving Confederate statues, has done little to earn credibility with the majority of minorities in this country. It’s unclear if the administration have even prepared to make a vaccine widely available should one be forthcoming, let alone devote resources to a campaign to educate Americans about its safety.

Should a Biden administration take the reins next year—and if by then there is a vaccine or one is in sight—they will need to shoulder the burden of not just making a vaccine accessible but calming fears that it could be a gateway to sterilization or worse.

And trust in a Democratic administration is not a given either.

After all, the Tuskegee experiments began during the year Franklin Roosevelt was first elected, and continued through several Democratic administrations until it was finally halted in 1972 when the study was exposed to the public.

In 1997, then President Bill Clinton formally apologized for the tragedy, and some of its survivors graciously accepted it—but rest assured Black America never forgot it.

Should there be a not insignificant resistance to a coronavirus vaccine in Black and brown communities, it could potentially be deadly not just for them but all Americans—and it would be yet another unforeseen calamity with roots in this country’s many racist sins.