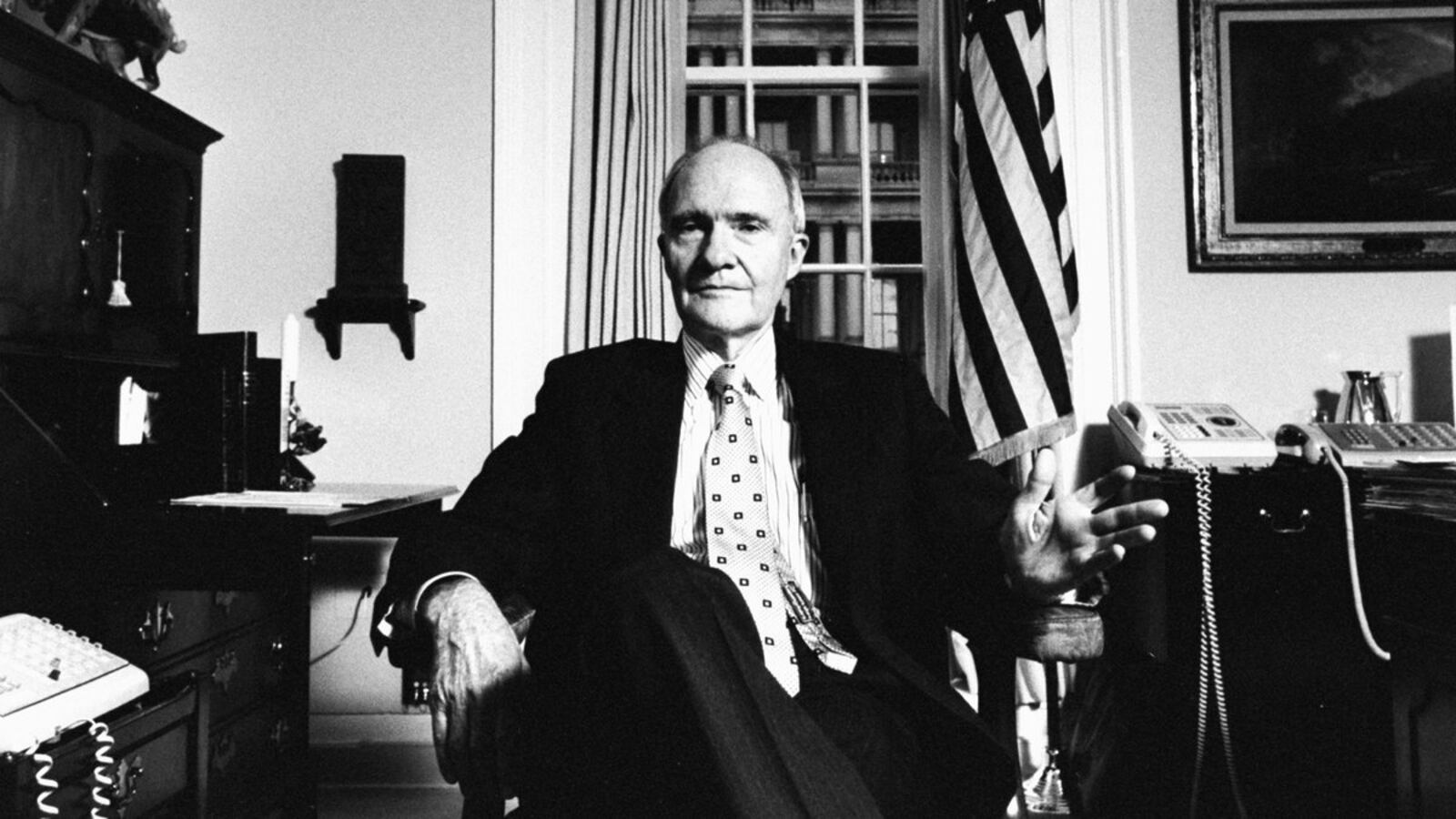

Quietly, and with extraordinary grace, deftness and skill, Brent Scowcroft, who died Thursday night at the age of 95, established himself as the standard against which all others in his field are measured.

Gerald Ford once told me that the smartest thing he ever did as president was to take the National Security Adviser post away from Henry Kissinger, who at the time held both it and the job of Secretary of State, and give it to Scowcroft, who had been Kissinger’s deputy. Kissinger got the limelight but among those who study how the government works or seek to serve effectively within it, it is Scowcroft who has produced the enduring and superior legacy.

By the second time Scowcroft became national security adviser, under his close friend George H.W. Bush, he had served on the Tower Commission which investigated Ronald Reagan’s dysfunctional National Security Council and came up with the critical recommendations about how to fix it. His experience from having served once before in the job, from having examined the role of the NSC in depth once it had been broken down, from having seen what had worked and what had not under Kissinger and Nixon, Ford, and then Reagan, and his relationship with Bush and Bush’s secretary of state, James Baker, provided the kind of preparation for the role that no one has had before or since. Under Bush, Scowcroft would be so successful in the twin roles of adviser to the president and “honest broker” among the members of the NSC and their teams, that the “Scowcroft model” has been the template for every national security adviser who followed him.

But in his intellectual rigor, his extraordinary work ethic, his leadership, his humility, his kindness, and his relentless desire to refine his worldview, to learn and to grow and to help others do the same, Scowcroft is more than just a model to the small club of those who devote their lives to the nuances of foreign and defense policy, the work of the intelligence community or the business of advising presidents. By virtue of his character, his work stands as a monument to all the virtues of public service that the current president and the vast majority of his senior advisers lack.

Scowcroft understood that formulating public policy was a team sport. Although he was a man of strong views, he was also a listener, constantly seeking to educate himself. He believed in facts and the skeptical analysis of their implications. He also believed that underpinning the decisions taken by the U.S. government and the actions of its leaders were considerations like ethics and values. That is not to say that he, like every senior U.S. policy official of the modern era, did not make mistakes in office. There is much to debate within the policy choices he made. He would be the first to admit that.

But even after his second term as national security adviser ended, he continued to play an influential role because of the degree to which he was seen to be genuinely searching for the right policy answers for the country, answers informed not just by our national interests but by what he saw as our national values—at least those to which we have traditionally aspired. Notably, during the administration of George W. Bush, this led to sharp differences between him and those pushing hardest for war with Iraq, notably Vice President Dick Cheney. He once told me, shaking his head over one of Cheney’s typically unilateralist arguments to expand the conflict, that, “I do not know what happened to Dick Cheney. He is not the man I worked with when he was Secretary of Defense. Something changed within him. There’s something dark there now.”

But as frustrated as Scowcroft, also seen as a champion of “traditionalist” American internationalism, could be with what he called the “transformationalists” in Cheney’s orbit, he was even more worried about the ascendancy of Donald Trump to be President of the United States. He confided to me and to friends and colleagues that he saw Trump as a dangerous choice for the presidency by virtue of both temperament and inexperience. He endorsed the candidacy of Hillary Cllinton. He was clearly shocked and disturbed by what he saw from the reality TV star turned commander-in-chief. But, at one event thrown to honor him that took place shortly after Trump was elected, Scowcroft cited Trump’s defects as precisely the reason that he encouraged those national security professionals who were given the chance to serve him to do so. “He needs you. Your country needs you,” he said according to one account of the event.

The contrasts could not be starker between the self-serving, corrupt ethos of the playboy-political dilettante like Trump and the West Point-educated, multilingual, spotlight-shunning Air Force lieutenant general who deeply believed in the ideal of a foreign policy community that sought to set politics aside. Losing a man like Scowcroft now is a great blow to his friends and his family, and it is a reminder of how profoundly Donald Trump and his enablers have debased the presidency, the conduct of U.S. foreign policy and our standing in the world.

If there is cause for hope, it is that while political opportunists like Trump come and go and the world is eager to forget them, men like Scowcroft become something more: enduring models, paradigms of how to serve this country properly, and well—and that someday soon we may hope it will be leaders aspiring to the standards set by this quiet, good man that restore our country, and our government, to their proper course.