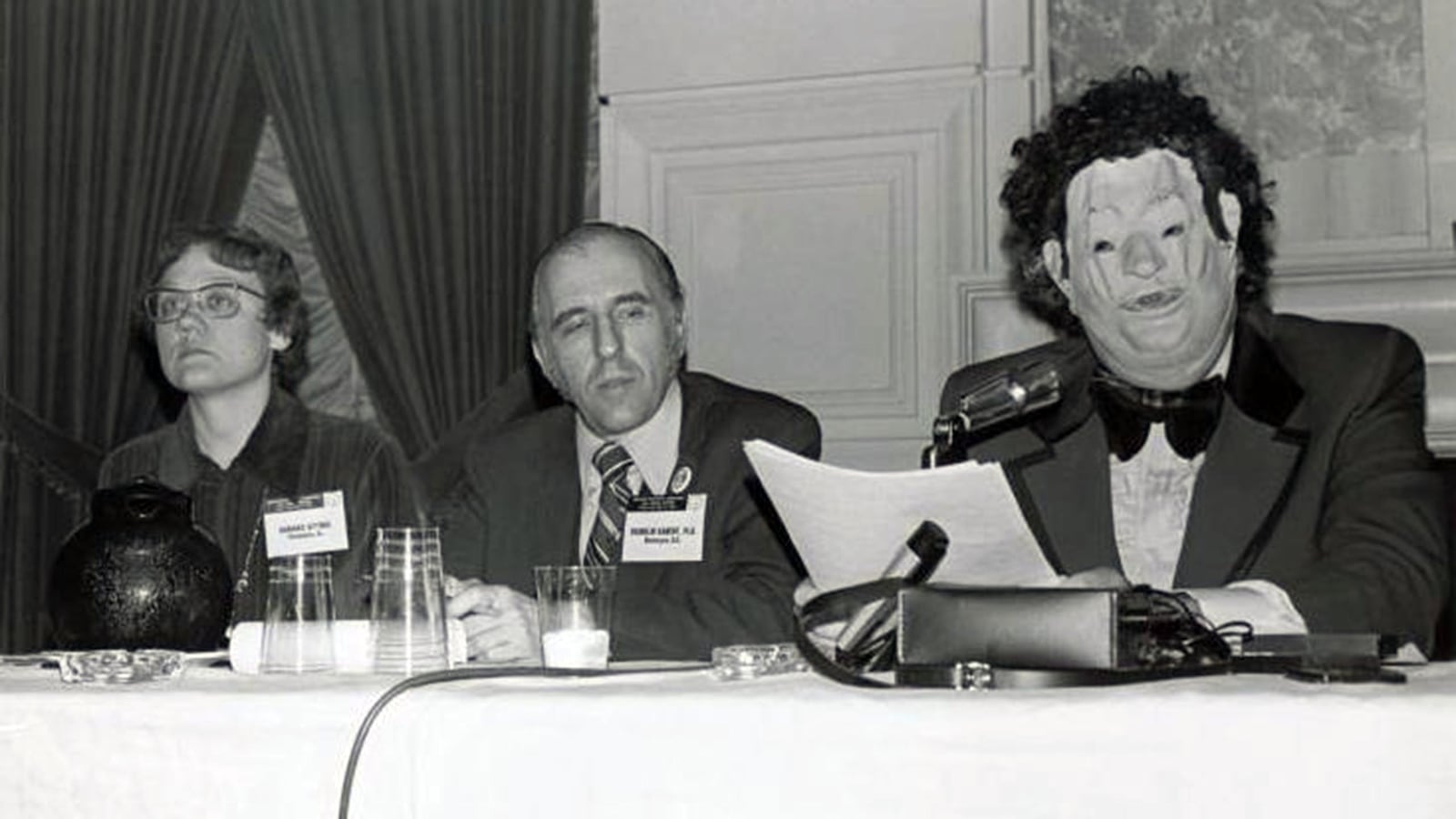

The mask that Dr. John E. Fryer wore in 1972 to deliver his speech about what it was like to be a gay psychiatrist to an American Psychiatric Association panel was not in any of the 217 boxes the playwright and director Ain Gordon discovered at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

But Gordon did eventually find out what had happened to that now-famous Nixonian mask, and much more about its wearer too.

It was at the Historical Society that Fryer’s papers were stored, and it is from what he discovered in the boxes in 2014 that Gordon created a play, 217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous, about Dr. Fryer and his legacy.

The play was first performed in Philadelphia in 2016, and is this week receiving its New York premiere at the Baryshnikov Arts Center.

He didn’t know it at the time, and he remained modest about it his whole life, but the speech that the masked Fryer gave—as the eponymous Dr. Anonymous—helped change the lives of generations of LGBT Americans, and continues to do so.

A year later, in 1973, the APA’s DSM (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) declassified homosexuality as a mental illness.

It was Fryer’s speech—which began “I am a homosexual, I am a psychiatrist”—that led not only to the change in APA diagnostic classification, but also to the many positives that flowed from it.

Other anti-gay laws could be challenged without their defenders using homosexuality-as-a-mental-illness as a significant weapon of prejudice. In addition, the APA’s declassification was the first official repudiation of those who sought to “cure” homosexuality. That battle continues today, with various states finally enshrining laws against so-called “conversion therapy.”

Fryer died, aged 65, in 2003. In October 2017, during LGBT History Month, a marker in his memory was unveiled directly opposite the Historical Society, as a testament to the significance of his legacy.

Gordon is particularly interested in “significant but obscure” figures, like Fryer, “who have been forced to the margins of history.”

He came across Fryer’s story while on a two-year residency at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. He was searching for “personal battles for public liberty,” and had not to date sourced queer history in his work. He hoped he would find something LGBT-related at the Society.

On his first day, the head archivist showed him a locked-away archive; on the left, the archivist told Gordon, were “steps towards an ideal civilization,” and on the right were “the stumbles along the way.”

Looking at the materials on the right, he alighted upon a copy of Drum magazine, a Philly-based 1960s LGBT periodical and within that mention of the prominent LGBT activist Barbara Gittings.

Googling away, Gordon then came across mention of the brave and trailblazing LGBT activist Frank Kameny, who, in a history-making Supreme Court case, challenged his own firing as a federal employee for being gay.

Then Gordon came across the picture of Gittings and Kameny sitting alongside Fryer at the 1972 panel, which Gittings and Kameny had lobbied the APA to convene. (Gittings died in 2007, Kameny in 2011.)

In 1971, Kameny had disrupted that year’s APA conference, saying, “We’re not the problem. You’re the problem,” said Gordon, leading to the organizing of the panel the following year, “Psychiatry: Friend or Foe To Homosexuals? A Dialogue.”

“What on earth is this?” thought Gordon when he saw the now-famous image of the panel. “It was shocking to me that it was 1972, not 1952 or 1962. As a writer and director, I was struck by the incredible theatricality of the image.”

The question facing Gordon was “how to revivify what making that speech, which was plain-spoken and not dramatic, was like at that moment.”

More Googling led Gordon to Dr. Fryer’s speech itself, and then the discovery that the Society had Dr. Fryer’s materials.

“I didn’t have the full context of his risk-taking until I started reading,” Gordon said. “He had already been fired once for being gay (in 1965, from an internship at the University of Pennsylvania), and then you think of the tenor of the times. It was close to the Stonewall Riots (of 1969). It was three years later. But we were not well on our way to equality.”

Gittings and Kameny realized they needed a gay psychiatrist to speak, but no one would agree, because they would lose their jobs; after all, being gay meant they were defined as mentally disturbed.

Malcolm Lazin, executive director of Equality Forum, which among other activities oversees the annual LGBT History Month and who is executive producer of the play, said Kameny knew that fighting for LGBT rights would be revolutionized “if society didn’t see us as loony tunes. Homosexuality as a mental illness was used as an underpinning to a lot of homophobic local state and federal statutes and regulations, and ‘cures’ which now look barbarian.”

The Boys in the Band, Mart Crowley’s 1968 landmark play now remounted in an all-gay star revival on Broadway, “totally makes the point about how that generation of gays had internalized societal homophobia,” said Lazin.

Through her Philly LGBT networks, Gittings found Fryer, then on the medical faculty at Temple University.

Fryer agreed to make the speech only if he could wear a mask, an oversized suit, use a machine to distort his voice, and use a pseudonym. He and a friend found a Nixon-like mask, which they further customized.

At the time a psychiatrist could lose their license to practice if their homosexuality was discovered, Lazin said.

Gittings and Kameny “recognized the strategic value and impact of John wearing the mask,” added Lazin. “It made its own statement about not being able to be open. John was risking his job. He had every reason to be concerned. He had been fired once, and could lose his position at Temple. Wearing the mask was both very powerful and very rational.”

“John didn't grow up in a homosexual family or a homosexual community, but he trained as a psychiatrist,” said Lazin. “He applied his learning to a better understanding of the condition that he and other homosexuals were in, and he concluded that the problem wasn't homosexuality. The problem was homophobia. In the speech, he was able to speak that to those in power.”

“The APA was open to change,” said Gordon, “but it happened faster because Fryer delivered his coup de grace. One of the things that fascinates me is that the mask is more famous than him: it’s such a metaphor for queer history. The outer behavior is what the public sees and remembers, not the event behind that.”

After the panel, Fryer did not want to be recognized out socially, so, said Gordon likely went back to the moderator’s hotel room for—he later recorded in his notes—whiskey, brandy, Scotch and Bourbon. Then he did an interview with a Dallas radio station, in which he read the speech out again.

Fryer subsequently spent a 30-year teaching career at Temple as a professor of both psychiatry and of family and community medicine. Gordon said Fryer was “very involved in the church” and church music. “He was very much an activist: when AIDS broke in Philly, he saw patients at his house. He had no real interest in claiming that famous moment.”

Fryer also “got very involved in setting up psychiatric studies around death and dying and how to help with bereavement,” said Gordon. “I don’t think he wanted to be held constantly to one moment earlier in his life. He never hid it or denied it, but he said, ‘I do all these other things.’ At the very end of his life he was thinking of selling up everything and going to Australia, living in the Bush and working with the poor populations contracting AIDS there.”

Fryer had “a large, florid personality,” said Gordon. “He was six foot four, a Southern man, and still very private. He was out to his friends, but not out at work. Most people weren’t back then. He was also not interested in heteronormative rules. He was not interested in monogamy, or getting married. He had lovers. He questioned—which in some ways also caused later iterations of the LGBT movement to disown him—marriage equality. He asked, ‘Why are we imitating straight people?’”

Fryer first declared his true identity, as the man behind the mask, in 1985. Gordon discovered papers dating to the early 1990s when a magazine contacted him to ask if “Dr. Henry Anonymous” had been him. “I guess they outed me,” Fryer had written on a piece of paper.

Gordon laughed, and said Fryer had an 18-room Victorian house and “hoarded crap, I can tell you. He kept every charge receipt—for underwear, for a trip to Guadalajara in 1996. He kept everything.”

His papers were not ordered chronologically, and though he kept so many papers and notes, said Gordon, he remains a private and elusive figure. “My portrait of him would shift box to box. Some boxes were so boring he’d seem such a drag, then the next box was so inspiring, then the next box he’d be such a jerk to his friends. It was like looking into a funhouse mirror.”

The actual mask, Gordon discovered, stayed on the top shelf of a closet for decades. One day, clearing out the closet with a friend, Fryer said, “Oh throw it away, it’s nothing.”

Said Gordon: “He really kept moving on with his life and career, there were other social issues and things he wanted to deal with.”

Fryer isn’t represented on stage in 217 Boxes. The actors play three different characters in his life, themselves speaking as spirits, who act as our guides to his life.

The activist Alfred A. Gross (Derek Lucci) worked with Fryer in the mid to late 1960s, pre- the 1972 speech, when Gross was Executive Secretary of the George W. Henry Foundation, an organization for gay men, who—as “sexual deviants” were being prosecuted for cottaging or soliciting—needed to find “empathetic” psychiatrists who could supply positive character references in court.

Katherine M. Luder (Laura Esterman) was Fryer’s secretary for 24 years after his 1972 speech, and “kind of his platonic wife,” said Gordon. She “organized everything” for Fryer, and when she died, aged 91, was still working for him. He organized her funeral and gave the oration.

The last character is Fryer’s father, Ercel Ray Fryer (Ken Marks). Fryer’s mother wrote him hundreds of letters, his father wrote around nine, “all signed ‘Love, Daddy,’” said Gordon, “which for a Southern man, born in 1901, un-college educated in the middle of the century is a big thing to say to a son, although I do not believe he ever acknowledged his son’s sexuality.”

The family, while not well-off, was socially conscious: Fryer’s father loaned money to poor farmers, and were opposed to the racial discrimination of the era in semi-rural Kentucky where Fryer grew up.

Fryer’s childhood “wasn’t terrible and it wasn’t great,” Gordon said. Fryer’s mother was “a bit of a depressive and had a miscarriage and post-partum depression at a time when they didn’t talk about this kind of thing. It was a bit Southern Gothic. She had what they called ‘the vapors.’”

Fryer’s father was a hard worker, and Fryer was close to his sister, “but John wanted to have a bigger stage in life. He was gay, he needed to get out of there.”

Writing to his parents from college, he still wrote about going out with girls, “although no girl lasts more than two letters,” said Gordon. “Some of his friends told me he was already active with other boys.”

The first time Fryer himself went into therapy, in Kansas as part of a residency before coming to Philadelphia, his psychiatrist told him, “I think some of your problems will be solved if you move to a large Northeast city.”

Gordon spent three days a week for 15 months working through as many of the 217 boxes as he could. As he did so, he confronted some of his own prejudices, he said. He found some receipts from the Venture Inn, “a very, very old gay bar in Philly that people called the Denture Inn.”

Fryer was going three times a week to the bar (which closed in 2016, having opened in the early 1970s), “buying all the drinks,” and Gordon thought to himself, “Oh John, you're like 60, and you’re going three times a week and buying drinks for these guys, come on John.”

And then, Gordon said, “I thought, ‘What the fuck is my problem? What is so bad about that? Get over it.’”

Another card yielded the name of a good friend of Fryer’s, and so, laughed Gordon, his own stupid prejudice ended up leading to the “greatest first-person research I could have asked for.”

I asked Gordon what he didn’t find out about Fryer. “I am not clear that his love life worked for him,” said Gordon. “I’m clear about his rejection of normalcy stuff, but there seems to be a holdover of going for unavailable men.”

David L. Scasta, M.D., a forensic psychologist and clinical associate director of psychiatry at Temple University, was a longtime friend of Fryer’s who first met him in 1979 when he was a resident at Temple.

Scasta recalled “a brilliant, brilliant man. He had an intuitive flair for knowing what you were feeling. The grin on his face seemed to suggest he had just heard the most scintillating story about you. He would have described himself as a ‘flamboyant’ gay man. He was a wonderful church organist. He could be fuzzy with boundaries.”

The first time they met, Scasta recalled the tall, 300-pound Fryer looming over him and a then-new-fangled word processor. Scasta instantly felt hit on, unwelcomingly. At the time Scasta wasn’t out, “partly to keep John away, and partly because I was scared professionally to be out.” Years later, Fryer hit on Scaster’s partner. Fryer wasn’t rude or unpleasant in any way, Scasta emphasized. Fryer’s lovers were not random, Scasta said, but regular, known partners he felt comfortable with who he would see a few times a year.

Scasta, who also teaches an introduction to LGBT issues to psychiatry residents at Temple, laughed. “John was not known for his humility. He was no Trump, but when John was in the room you knew was in the room. He was dramatic and always friendly, the life of the party.”

In 2002, the year before he died, Fryer received two awards, a “distinguished alumnus” award from Vanderbilt University, and a Distinguished Service Award from the organization now known as the Association of LGBTQ Psychiatrists.

When asked what he hopes a 2018 audience will glean from 217 Boxes, Gordon cited what the character of Alfred A. Gross says during the play: that he is the “Cro-Magnon of homosexual freedom, so he (Fryer) could stand upright, and so you (the audience) could march.”

Gordon also hopes his play conveys “some of the tiny steps that led to where are now, some that are usually overlooked. We are also slightly trying to say there is still work to be done, and that work never ends. If anything, liberals have a tendency to think that once we’ve achieved something we’ve got it dealt with. But those against us always strategize to turn things back, and we have to be vigilant.”

For Lazin, “I think John Fryer is certainly among the top five figures in terms of their impact on the LGBT civil rights movement. Without him I really do not believe the APA would have removed homosexuality as a mental illness the following year.

“Once they did that you’re certainly removing, with some exception, electric shock therapy, chemical castration, lobotomies. In terms of so-called ‘cures,’ those who were involved in the cottage industry of ‘curing’ gays tried to fight back, and tried to reinstate homosexuality as a mental illness. And we have the last vestige of that in terms of reparative therapy, and the current fight to outlaw it.”

That ongoing struggle mirrors the struggles that continue today, rooted in Kameny’s brave fight, around fighting discrimination in the military and the efforts to federally outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

For Lazin, such significant victories as Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, which saw the striking down of the Texas sodomy law, wouldn’t have occurred if homosexuality were still considered a mental illness.

Scasta doesn’t think Fryer recognized his own significance, or his own courage. When Fryer delivered the 1972 speech again to a group of LGBT psychiatrists in Dallas many years later, Scasta recalled, he did so without any self-aggrandizement.

“His impact was huge,” said Scasta. “For the first-time, in 1972, psychiatrists were exposed to another psychiatrist who was gay.”

In 2013, Scasta himself composed the latest “incredibly affirming” pro-LGBT APA statement. When he thinks about Fryer today, he recalls that memorable meeting at the word processor, and also Fryer's speech in Dallas, many years later, its ground-breaking orator now wearing no mask.

“It was riveting,” said Scasta. “It made you proud to be gay.”

217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous is at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, Jerome Robbins Theater, 450 West 37th St., New York City, until May 11. Book tickets here.