Some whistleblowers work inside the system, informing their bosses that something’s amiss. Others go outside, clueing in reporters, legislators, or regulators. A low moment in American history—the My Lai massacre in Vietnam—produced both kinds of truth-tellers. An army helicopter pilot, Hugh Thompson, Jr, along with his crew members Glenn Andreotta and Larry Colburn, saved Vietnamese villagers from American fire during the killings. Thompson then reported the horrors up the chain of command—which tried to cover it up.

If it were not for a man named Ronald Ridenhour, however, the horrors of My Lai may never have come to light—and he deserves the most credit for forcing Americans to confront how some soldiers behaved in Indochina.

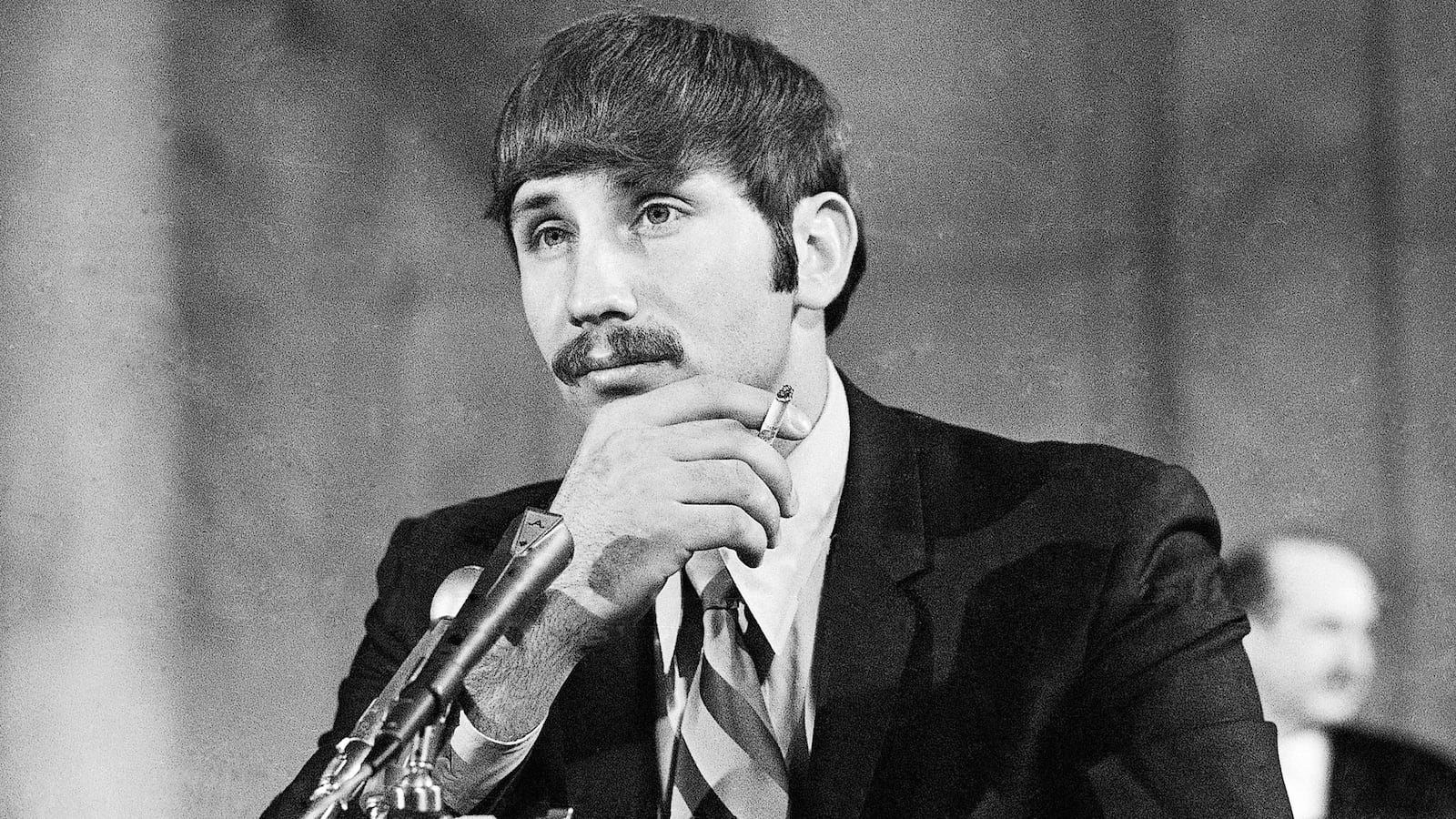

Fifty years ago, Ron Ridenhour was a grunt—a bit player in the Vietnam horror show. As a door gunner on an observation helicopter, he heard rumors shortly after March 16, 1968, of Americans shooting unarmed villagers.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ridenhour started collecting testimonials, informally. In March, 1969, he sent a detailed report to 30 members of Congress, along with President Richard Nixon, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Secretary of Defense.

“The question most often put to me,” Ridenhour later recalled, “was not why had they done it, but why had I done it. In a word, justice.” He admitted: “I was younger and more foolish then.”

A classic Baby Boomer, born in 1946, he was raised on words like justice and honor. “They lived,” he wrote. “They breathed. They were the flesh and blood of American political tradition, embodied daily” in the nation’s policies.

Unfortunately, like many Boomers, Ridenhour’s romanticized vision of America didn’t survive the Vietnam jungle. Some buddies of his transferred into “C” Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry. In March, 1968 they neutralized a “notorious” area in South Vietnam nicknamed “Pinkville.” These soldiers had suffered heavy casualties in other search-and-destroy missions. Their superiors warned them that the villages were crawling with armed Viet Cong supporters.

Nevertheless, Ridenhour was shocked when his friend “Butch” Gruver described how soldiers mowed down as many as 504 civilians in the hamlet of My Lai, near Son My. Butch recalled “seeing a small boy, about three or four years old, standing by the trail with a gunshot wound in one arm. The boy was clutching his wounded arm with his other hand, while blood trickled between his fingers… Then the captain’s RTO (radio operator) put a burst of 16 (M-16 rifle) fire into him.”

One soldier shot himself in the foot to flee the violence. Gruver singled out one officer, Lieutenant William Calley, who rounded up villagers enthusiastically. He then ordered others to shoot them or machine-gunned them himself.

Ridenhour consulted his closest C Company friend. Mike Terry reported that, after finishing lunch, they shot badly wounded civilians to be merciful. Calley shot them in cold blood.

“Eating must have been difficult,” Ridenhour imagined. “There were dead Vietnamese everywhere.” After all, “the undead in the ditch had begun to cry out… It must have been a terrible sound, all that flopping and slapping of flesh, the crying, all that agony out there polluting a now otherwise peaceful morning.”

As Terry spoke, Ridenhour’s “head felt like it must feel when someone is scalping you alive. Even as it is actually happening, you can’t bring yourself to believe it. But yes, yes, yes, he said on every detail. It was all true.”

Terry sighed: “It was like a Nazi kind of thing.” Another buddy reported that Calley’s “men were dragging people out of bunkers and hootches and putting them together in a group” to be shot.

It was equally stunning that “so many young American men participated in such an act of barbarism,” and “that their officers had ordered it.” Ridenhour felt “an instantaneous spark of anger that soon grew to rage. I decided that I would track down the story. If it was true, then the chips would land where they fell.”

When he sent his letter in March, 1969—after being discharged—Ridenhour approached politicians and not reporters, because, “as a conscientious citizen I have no desire to further besmirch the image of the American soldier.” But the commanders and politicos responded half-heartedly.

Even journalists mostly overlooked it when the Army charged Calley in September, 1969. Seymour Hersh, the freelancer credited with breaking the story in November, would write that My Lai “remained just another statistic until late March, 1969, when an ex-G.I. named Ronald L. Ridenhour wrote letters…”

For the next two years, Calley’s case finally gripped America. Some condemned Calley’s crimes. Others grumbled that he alone was scapegoated. Most resented that a soldier whom they decided was doing his duty, and who claimed he was following orders, was prosecuted by superiors and hounded by reporters.

Ultimately, Calley was the only soldier convicted. Though sentenced to life in prison, he served three days in jail before President Nixon ordered him to be released to house arrest. A jury acquitted his commanding officer, Ernest Medina.

Nevertheless, the whistleblowers on My Lai changed American history.

In the 1960s, such informants were considered “snitches.” Then, the consumer crusader Ralph Nader fought to honor such truth-tellers as “whistleblowers,” evoking old-fashioned police officers who blew whistles while chasing bad guys. Today, various regulations protect those who expose systemic wrongdoing—although one person’s single-minded whistleblower remains another’s double-crossing traitor.

Thompson paid the whistleblower’s price, staying in the army and enduring harassment. Ultimately, he was vindicated, receiving military citations and seeing case studies analyzing his heroism taught broadly.

Ridenhour parlayed the skills he developed uncovering My Lai into an award-winning career as an investigative journalist—until he died suddenly while playing handball in 1998 at the age of 52.

With each telling of his tale, Ridenhour became more bitter. Insisting that it wasn’t just “some lowly second lieutenant who went berserk,” he deemed “the massacre… the logical outgrowth of overall U.S. military policy in Vietnam.” Even “the distressingly enthusiastic” Calley, he believed, “was following orders.”

In 1973, during the “Medusa of Watergate,” Ridenhour mourned “the moral chaos of a people who have too long allowed themselves to be manipulated into accepting the Nixonian sophistry that whatever is expedient is necessary; whatever is necessary for the protection of Richard Nixon is legal; whatever is legal is both moral and ethical.” Nixon, he claimed, “made a bitter porridge of that justice I set out so long ago to find.”

Twenty years later, Ridenhour still complained that “neither the military nor the U.S. government has made any effort to come clean with the American public, the Vietnamese people or the rest of the world regarding the reality of our deplorable conduct in Vietnam.”

Still, most historians agree with Professor Howard Jones that My Lai “galvaniz[ed] the antiwar movement… ultimately helping to end American involvement in Vietnam.” More profoundly, the historian David Greenberg adds, “The disclosure of atrocities not only moved public opinion further against an already unpopular war… it raised fundamental and unsettling questions about who were the good guys and bad guys in Vietnam, and why we were there at all.”

Although such stories muddied the veterans’ homecoming, Greenberg adds that, “as dark deeds often do, the actions of Charlie Company also led eventually to stronger and clearer rules of conduct for American soldiers in wartime and a resolve within the military to resist the pressures toward cruelty that war inevitably brings.”

Undoubtedly, then, as now, whistleblowing took great courage. And sometimes, then, as now, it achieves what Ridenhour hoped it would. Ridenhour’s letter misquoted Winston Churchill to the effect that, “A country without a conscience is a country without a soul, and a country without a soul is a country that cannot survive.”

Ridenhour and others righted wrongs, saved the nation’s soul, and focused Americans on living their values, not violating them, so indeed we could not just survive, but start to heal.

Additional Reading:

Seymour M. Hersh, “The Massacre at My Lai: A Coverup and Its Killings,” New Yorker, January 22, 1972.

Howard Jones, “The Whistleblowers of the My Lai Massacre,” History News Network.

Howard Jones, My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness (2015), edited by David Greenberg.

Ron Ridenhour, “Jesus Was a Gook,” Part I and Part II

Ron Ridenhour, “PERSPECTIVE ON MY LAI: ‘It Was a Nazi Kind of Thing’: America still has not come to terms with the implications of this slaughter of unarmed and unresisting civilians during the Vietnam War,” Los Angeles Times, Mar. 16, 1993