The cry of “America First” is back with a vengeance. Which makes it the perfect time for a look back at Republican Sen. Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan—a leader of congressional isolationists, an obstreperous opponent of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and one of the unsung heroes of 20th century American politics.

As Hendrik Meijer writes in his excellent new biography, Arthur Vandenberg: The Man in the Middle of the American Century, Vandenberg played a major role moving the GOP toward internationalism—helping to create the institutions and alliances that comprise the liberal world order that’s coming apart today.

Like many Midwestern statesmen who rose to influence during the interwar period, Vandenberg’s outlook was shaped by the First World War, an ambiguous conflict with an even more ambiguous outcome. As editor of the Grand Rapids Herald, Vandenberg had high hopes for the Paris Peace Conference, which he hoped would “bequeath a reign of justice to the world.” As it became clear that the postwar arrangements—namely, the feckless League of Nations and the punitive Versailles Treaty—were failing to instill this vaunted sense of “justice,” Vandenberg adopted an attitude of “vigorous neutrality” in world affairs.

Soon after his election to the Senate in 1928 and the subsequent onset of the Great Depression, Vandenberg emerged as one of most prominent critics of government intervention both at home and abroad. He attacked FDR’s “New Ordeal” and advertised himself as an advocate of “insulation,” not “isolation.” Vandenberg played an instrumental role in the 1930’s hearings led by fellow Midwestern GOP non-interventionist Gerald Nye, which attempted to pin the blame for American involvement in World War I on banking and financial interests. Echoing prairie populist William Jennings Bryan, who four decades earlier implored the nation’s bankers not to “crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” Vandenberg decried “a war system that has crucified this world for a thousand years.” He promised to protect U.S. neutrality against “international emotionalism” and “appetites which love commerce in spite of casualties.”

Motivated by an intense distrust of Roosevelt, Vandenberg stood foursquare against the president’s foreign policies aimed at shoring up Europe’s democracies against the rising tide of fascism. “For Vandenberg, neutrality remained the holy grail of American foreign policy,” Meijer writes in his biography.

Like many critics of FDR’s domestic policies, which brought about an unprecedented centralization of power in the federal government, Vandenberg feared another world war would give the president dictatorial powers. “We must not lose democracy at home in an effort to save it abroad,” he warned.

Thus, Vandenberg opposed trade embargoes on a belligerent Japan. As for the policy of “lend-lease,” by which the United States sent its future wartime allies weapons, warships, and aid, he decried it as “war by proxy.” So frustrated was FDR by the knee-jerk opposition of Vandenberg and other Senate isolationists that he vented to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, “I think we ought to introduce a bill for statues of Austin, Vandenberg, Lodge and Taft, to be erected in Berlin and put the swastika on them.”

Vandenberg, like most of the rest of his countrymen, would be jolted out of his isolationist convictions by the shock of Pearl Harbor. The Japanese surprise attack effectuated what he would later write was “a perfectly simple and obvious mental process under the impact of war,” forcing the United States into a conflict which “must be fought to a conclusive finish and to a peace-for-keeps.” Not for him the stance adopted by latter generations of isolationists, who have always found a reason to blame America for the misfortunes that befall it. Vandenberg’s abrupt reversal could be attributed to that famous dictum often misattributed to John Maynard Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind.”

And so it was that this erstwhile sympathizer of the “America First” movement came to speak of his country’s world role in terms befitting what is now routinely derided as a “globalist.” No longer could Washington choose “insulation” over global engagement; momentous events overseas increasingly had a way of impacting America as never before.

In the crucial postwar period stretching from 1945 until Vandenberg’s death in 1951, the United States undertook a series of momentous decisions to rebuild Europe, arm it against Soviet subversion and construct a world order based upon liberal and democratic values such that great power conflict would never again erupt into war. Looking back on this time today, we take for granted the establishment of institutions like the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, as well as initiatives like the Marshall Plan. But by no means was America’s postwar internationalist posture inevitable, and Arthur Vandenberg deserves a great deal of the credit for ensuring that it was.

That’s because the lessons Vandenberg gleaned from the catastrophe of World War II were the opposite of those he had taken from the great conflict which preceded it. Whereas in the 1920s and ’30s, Vandenberg promoted a Fortress America strategy that would supposedly keep the world’s problems at bay, by 1945 he spoke for “The wise voice of American intelligence and enlightened American self-interest which [says] that a bad world for others cannot be a good world for us.” Having expended a great deal of blood and treasure fighting for other people’s freedom on three continents, many Americans—Republicans especially—were ready to leave those warring Europeans and Asians to their own devices. Fearful that a retreat into isolationism would just restart the vicious cycle that had led to war, however, Vandenberg fought a valiant battle within his party to bury “the miserable notion (so effectively used against us in many quarters) that the Republican Party will retire to its foxhole when the last shot in this war has been fired and will blindly let the world rot in its own anarchy.”

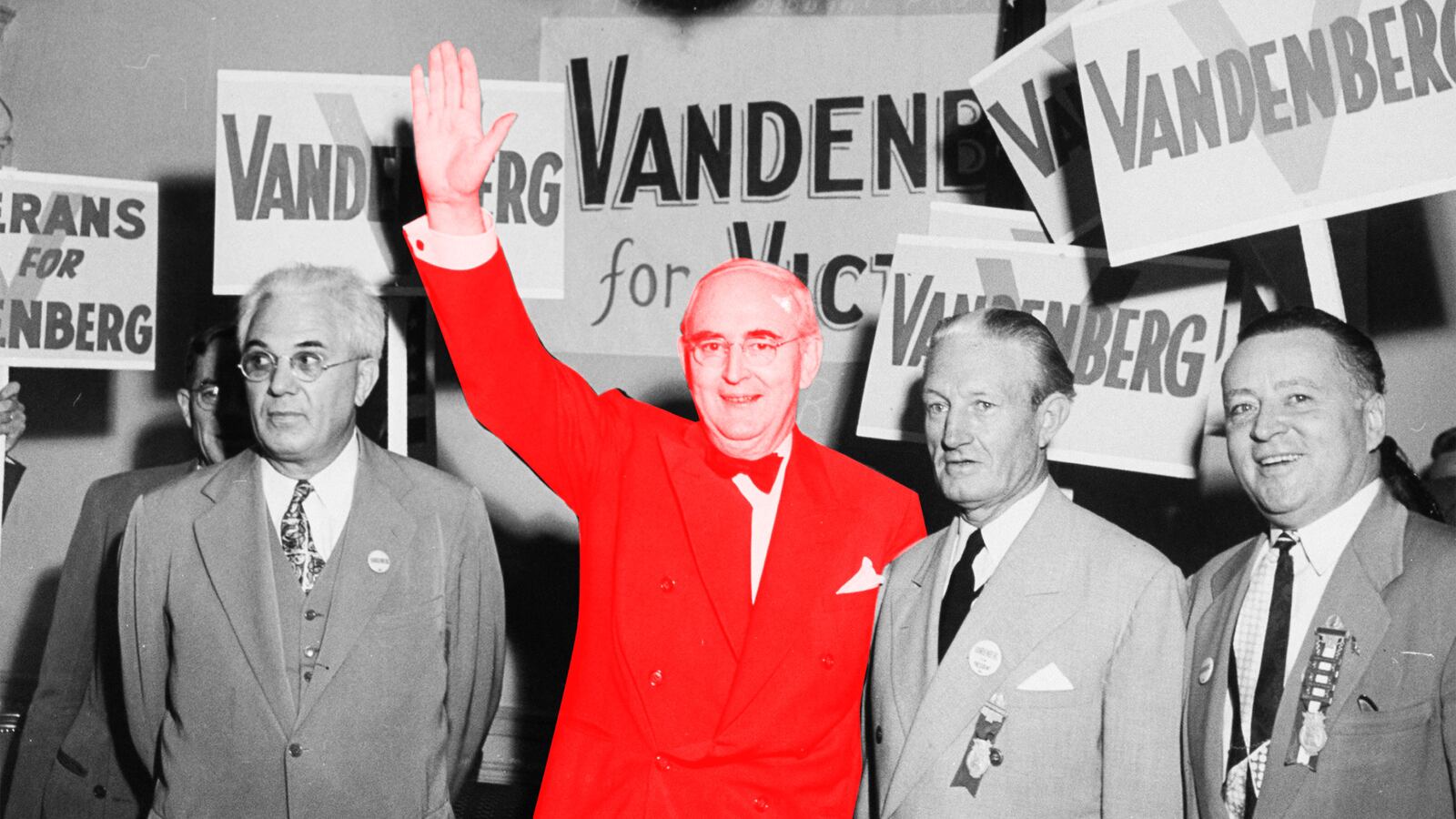

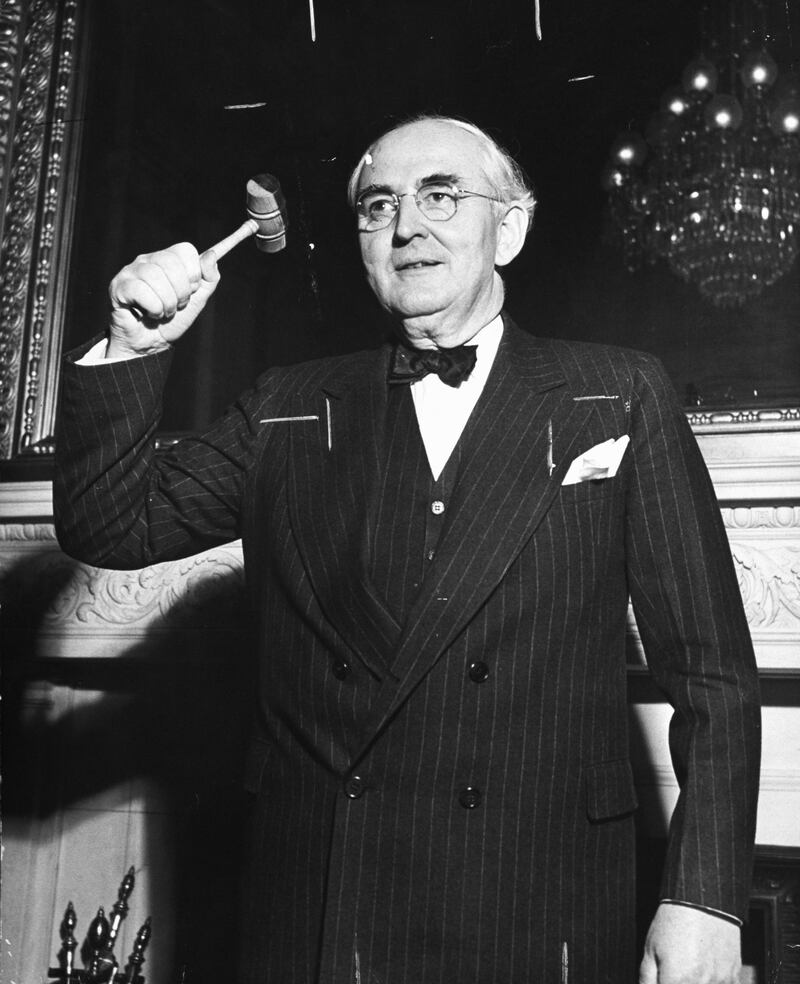

Senator Arthur A. Vandenberg presiding over a meeting during the GOP Caucus. (Photo by George Skadding/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

George SkaddingAn experienced foreign policy hand by this point, Vandenberg formed a crucial partnership with his former Senate colleague Harry Truman, who succeeded FDR in the White House after the latter’s death in April 1945. Three months prior, Vandenberg had delivered a “speech heard round the world” from the well of the Senate, charting his own ideological transformation, or what he termed, “confession.” Establishing that “I have always been frankly one of those who has believed in our own self-reliance,” he explained that “I do not believe that any nation hereafter can immunize itself by its own exclusive action... Our oceans have ceased to be moats which automatically protect our ramparts.” Calling out the clear effort by Soviet Russia—then still a wartime ally—to establish “a surrounding circle of buffer states, contrary to our conception of what we were fighting for in respect to the rights of small nations and a just peace,” Vandenberg endorsed the principle of “collective security,” the basis of the military alliance, NATO, for which he would help garner Republican support four years later.

Just weeks after assuming the presidency, Truman dispatched Vandenberg to San Francisco, where representatives from dozens of nations were gathering to create the United Nations. Sitting opposite Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov and witnessing the Russians’ underhanded tactics, Vandenberg became a determined Cold Warrior well over a year before Winston Churchill would deliver his famous “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri. Of the Soviet attempt to seat representatives of their puppet states in order to rack up more votes, Vandenberg wrote in his diary: “This is the point at which we line up our votes... and win and end this appeasement of the Reds before it is too late.”

Sounding like a Reaganite, he bemoaned the lack of moral clarity in diplomatic repartee, “the miserable fiction… that we somehow jeopardize the peace if our candor is as firm as Russia’s always is.” Meijer convincingly argues that the confrontation in San Francisco, largely passed over in histories of the Cold War, can be attributed as marking “the onset” of that twilight struggle as much as any other incident. The experience certainly emboldened Vandenberg, who came away convinced of the Soviets’ expansionist ambitions and the need for a firm, American-led response. “He had faced off with the Soviets while so many of his countrymen still accepted the ‘one world’ bromides of wartime alliance and the vague promise of a new United Nations,” Meijer writes.

Following the creation of the UN, Vandenberg was instrumental in obtaining Republican support for the Marshall Plan, lauded by Churchill to be “the most unsordid act in history” not least because, unlike Allied policy after World War I, it was designed to rebuild defeated Germany into a robust and economically prosperous Western democracy. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Vandenberg backed Truman’s call to arm anti-communist fighters in Greece and Turkey, (a policy that earned the president an eponymous “doctrine”), and the creation of NATO. When some of his GOP colleagues complained about the costs or burdens of these initiatives, Vandenberg famously admonished that “we must stop partisan politics at the water’s edge,” a nice sentiment that could hardly be said to have lasted that long after the end of the Second World War, if it ever really existed at all.

Arthur Vandenberg had a quality that was and remains rare in politics: the ability to admit he was wrong. Though it took a surprise attack on America to change his mind, Vandenberg ultimately realized that the world is not zero-sum. The United States, he came to believe, has a vested interest in a prosperous and democratic community of nations, and we are safer and stronger because of his wisdom, foresight and commitment to bipartisanship. His is a legacy from which we all—especially those so callow and historically ignorant as to bellow “America First”—can learn.