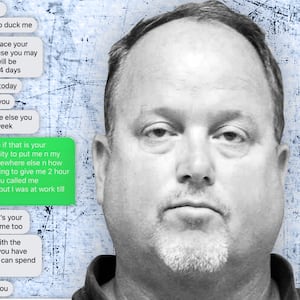

When Art Acevedo was appointed the Miami Police Department chief in April, he was praised as a reformer and the “Tom Brady” and “Michael Jordan” of police chiefs by the city’s mayor.

But just six months into his tenure, Acevedo’s failure to quickly learn the ropes of Miami’s notoriously nasty city politics—and his decision to air them out in a widely circulated memo last month—may cost him his job, city officials and insiders close to the matter told The Daily Beast.

“It’s just a ticking clock at this point,” one city official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, told The Daily Beast.

ADVERTISEMENT

Acevedo declined to comment for this story, telling The Daily Beast he has been “prohibited” by the city from speaking.

Acevedo was previously the chief of police in Houston. After being sworn in this past April, Acevedo quickly made enemies within the Miami rank and file when he fired veteran officers and demoted others. In September, he was criticized for telling officers the city's police force was run by the “Cuban mafia.”

Under fire from a contingent of city commissioners, Acevedo released a scathing memo on Sept. 24 to the city manager and mayor. He called out commissioners for undermining internal investigations. He also called out his loudest critic, city commissioner Joe Carollo, for allegedly attempting to use the police department as his “personal enforcer” against political enemies and said Carollo and another commissioner, Alex Diaz de la Portilla, provided him with a “target list” of businesses the department has “wasted untold hours” investigating based on the commissioners “whims.”

In subsequent city commission meetings, both commissioners denied the claims in the memo. In one meeting earlier this month, Carollo said that if Acevedo wanted to arrest him for any wrongdoing, he should “come right now and do it himself.”

“Here I am,” Carollo said.

Commissioners Carollo and Diaz de la Portilla did not respond to requests for comment.

Miami City Manager Art Noriega said in a statement to Local 10 that while issues surrounding Acevedo had played out “publicly,” the disputes were now “a personnel matter between an individual employee and the City.” Noriega declined to comment on this story.

Miami Mayor Francis Suarez meanwhile said in his own statement to the outlet that he has “full faith and confidence” in Noriega’s ability to “manage this situation.” Suarez did not respond to a request for comment.

Despite the distance from Acevedo’s memo, Bill Fuller, the owner of dozens of properties and businesses in Carollo’s Little Havana district, said it seemed to provide proof of something he’s been suspecting for some time. Fuller, who filed a lawsuit against the city of Miami right after Acevedo’s memo dropped, told The Daily Beast that two businesses he owns, including the famed Ball & Chain restaurant and bar on the Calle Ocho strip, have been targeted by late-night code enforcement investigations that include numerous members of the Miami police department and look more like a “drug bust.”

Fuller said the harassment was part of a “political vendetta” Carollo has against him and was pleased Acevedo aired out the issue. Now, he hopes it will be fully investigated despite the chief’s turmoil.

“He opened that door,” Fuller told The Daily Beast of Acevedo’s memo. “At this point it’s public and we need to have a full understanding of what all that means.”

Taquerias El Mexicano in Little Havana, Miami, Florida.

Google MapsIn a statement to The Daily Beast, Miami City Attorney Victoria Méndez said the lawsuit by Fuller and his business partners was an attempt to “deflect their illegal management of properties” and “blame their unclean hands onto the city of Miami.”

Despite its bombshell claims, Acevedo’s memo was quickly cannibalized by two commission meetings last week that served as forums for commissioners, and in particular Carollo, to air grievances against Acevedo.

At a Sept. 27 meeting, Carollo rehashed previous issues with Acevedo since he became chief. He also read accounts of alleged misconduct surrounding Acevedo at previous departments, The Miami Herald reported. At one point, Carollo presented an image of the chief dressed as Elvis during a fundraiser and criticized the costume as being too tight around the crotch.

In a subsequent Oct. 1 meeting, Carollo said Acevedo’s memo was an attempt to “blackmail” him and other commissioners.

After the two meetings last week, Acevedo was ordered by the city manager to submit a new plan for his approach to the chief job moving forward.

This week, Acevedo submitted a much more subdued “plan of action” for the next 90 days that acknowledges some “friction and missteps” since he joined the department from the outside. He said city leaders in Miami have a “unique” style different from anything he’d previously encountered and that he might have “moved too quickly” to make changes. He promised to meet with all commissioners in the next month to “repair” relationships.

But according to city officials with knowledge of the matter, the damage between Acevedo and the city commission is probably irreparable. “The day he sent the memo, he was basically saying he’s out of here one way or the other,” the official told The Daily Beast. “The way he wrote it, wasn’t like, ‘Hey guys, let’s all come back from this’, it was ‘I’m gonna double down and we’re going to war’.”

The sentiment was shared by Richard Rivera, the former member of a city police oversight panel from 2018 to 2020.

Although the decisions on hiring and firing a police chief rest with the city manager, Rivera told The Daily Beast commissioners in Miami have a “tremendous amount” of influence over the police department because they control the department’s budget. In the past, he said, they’ve cut back on positions or taken away resources from the department to weigh in on decisions. He said they’ve also been known to wield their influence over the city manager when it comes to hiring and firing.

“They apply the heat at that pressure point,” Rivera said.

Noriega, the current city manager, declined to comment.

Rivera said he believes Acevedo’s troubles started before he ever set foot in Miami.

In March Acevedo’s appointment as chief was made and bypassed an interview process with internal candidates, Rivera said. He also said Acevedo’s role as an outsider in the city, despite his Cuban heritage, didn’t help him fit in right away.

“It doesn’t matter that he’s Cuban,” he said. “They don’t look at him as a Miami Cuban.”

While he understood why Acevedo penned his memo in September, Rivera said the decision is a tell-tale sign that the outspoken chief, with nearly 100,000 Twitter followers, was unfamiliar with his new terrain. “He has to understand that this is Miami. It’s a universe unto itself,” Rivera said. “If you can’t navigate that, that’s to your own detriment.”

Despite the heat Acevedo received for the memo, Fuller, the Little Havana real estate developer, said he hopes the chief’s claims aren’t brushed aside as Miami political theater.

In the memo, Acevedo said he would be providing information about the alleged city hall corruption he’d witnessed to the “proper authorities,” which have made some speculate as to whether there could be an FBI probe.

The FBI did not respond to a request for comment.

At the Oct. 1 city commission meeting, commissioner Kenneth Russell, who’d skipped the previous Acevedo roasting session, said that as a result of the memo the issues in them would be “ripe for litigation” and that anything else said by city leaders could “put the city at risk.”

The city is already contending with Fuller’s $27-million lawsuit. It claims the city has been well aware of Carollo’s harassment of two of his businesses since January 2018, shortly after Carollo, who has held many positions within the City of Miami that of mayor, was elected as commissioner. Currently, both businesses are temporarily closed because of code violations.

The Ball and Chain in Little Havana, Miami, Florida

James Nesterwitz / Alamy Stock PhotoThe suit alleges that after Carollo won his seat he began seeking “retribution” against Fuller because he supported his political opponent during the tight race. That included repeated visits from code enforcement investigators and police officers under the guise of possible violations of city code.

But instead of issuing quiet violations, the suit alleges Carollo and others made sure the inspections took place at nights and on weekends and included several armed police officers so that they resembled “gestapo-style-raids” that would scare away customers.

Late one night in August, the police department arrested the general manager of one of Fuller’s restaurants in front of patrons for allegedly not having the proper license to operate the establishment. The charges were later dropped, according to court records.

According to the suit, the “developed and deployed” plan to run Fuller’s businesses out of town has now extended beyond Carollo and has “corrupted every organ” of the city government.

Before Acevedo’s memo in September, the suit alleges Carollo’s alleged corruption was called out by the previous chief of police, Jorge Colina.

In a February 2019 letter reviewed by The Daily Beast, Colina wrote to the city manager at the time, expressing concern with a new resolution that would allow Miami Police officers to be part of a task force to conduct site inspections. The resolution in question was passed after a city commission meeting in which Carollo brought up concerns about Fuller’s properties in Little Havana, the Miami Herald reported.

Colina wrote that the discussion of the resolution was “aimed at one particular business in the city,” which he said, “gives the impression that the city is selectively targeting his business for new investigations.” He wrote that he was concerned the request would be “unlawful.”

Colina did not respond to a request for comment.

Fuller, who is part-Cuban, told The Daily Beast it is ironic that his alleged treatment by city leaders resembles the sort of regime people like Carollo, who was born in Cuba, fled.

“The exact same tactics where you intimidated businesses, you send police forces in to close down shops and arrest people,” Fuller said. “That’s not what we know in the United States.”

His concerns echoed that of Acevedo, who was also born in Cuba and left to California at age 4.

In his now infamous memo, Acevedo closed by saying he’d been told many times that if he gave the commissioners what they wanted, he’d be left alone.

But he said if he were to give in to some of the things he’s witnessed during his short time in Miami, he might as well have remained in Cuba, “because Miami and MPD would be no better than the repressive regime and police state we left behind.”