Have you ever been grateful for something that you find aesthetically revolting? The caustically violent “This Is America,” Donald Glover’s latest single and video under his musical moniker Childish Gambino, is exactly that.

The song, which blends jazz, hip-hop, and South African melodies to deliver a scheming-up mantra of “get your money, black man,” takes on an entirely different tone when paired with its Hiro Murai-directed music video that depicts Glover maniacally dancing while simultaneously murdering black people in pastoral tableaus.

I am not revolted because I find the images triggering—horror has always been an engagingly provocative way to ensnare viewers—it’s because I find the entire endeavor nihilistic. Nihilism is not a genre that appeals to me, perhaps because it feels atheistic. It’s the absence of hope, a light at the end of tunnel or reasoning for madness. And more often than not, nihilism attempts to indict its audience. It calls to mind Michael Haneke’s 1997 Austrian thriller Funny Games (and its shot-for-shot 2007 English-language remake) that accuses spectators of partaking in the violence they’ve watched unfold. It’s not dissimilar from I, Tonya, the recent Oscar-nominated film that invites its crowd to laugh at the horrors inflicted on its lead, then lays the blame for her misfortune at our feet.

Nihilism is rare in black art, perhaps because of the bleakness of the American black experience. As Native Son author Richard Wright once said, “If Poe were alive, he would not have to invent horror; horror would invent him” when describing the “oppression of the negro” as his chosen writing subject. It’s hard to conjure a horrific portrayal of the black experience when the societal ills that would be drawn to metaphor—police brutality, the prison-industrial complex, the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and other hate groups—would fail to be more frightening than their origin. It’s why in Jordan Peele’s Get Out, the far-fetched premise is comical when compared to the subjugation of the black body it is satirizing. It’s why Peele veered away from his original ending, where Daniel Kaluuya’s character is incarcerated—it would be a nihilistic ending that veers too close to documentary rather than horror.

Glover of course knows this. As an artist, he’s always been hyper-aware of the image he’s presenting to audiences—and knows full well that his initial fandom was predominately white as he deepens his work to explore the diversity of black life. He has been accused of putting on personas, or playing to a white gaze, so why show images of black violence to a black audience that already has these images seared in their mind? What purpose do they serve? As I said, I do find the images abrasive, but I also find them necessary in the further development of black art.

“This Is America” has been accused of taking shots at black consumerist and hip-hop culture, but if anything the video celebrates that. Glover’s television series Atlanta shows that he adores black culture, even if he may not always get it right (particularly with his depiction of black women, like in this scene from “Robbin’ Season”). The song features vocals from Young Thug, 21 Savage, Quavo, Rae Sremmurd’s Slim Jxmmi, and BlocBoy JB. As he returns the refrain “get your money, black man,” he’s celebrating black ingenuity in times that reward it with violence.

Recently, Ta-Nehisi Coates explored Kanye West’s search for white acceptance, that seems to mirror Michael Jackson’s. On Jackson, Coates wrote: “There was the matter of his face, which took me back to the self-hatred of the ’80s, but this seemed not to matter because I was watching a miracle—a man had been born to a people who controlled absolutely nothing, and yet had achieved absolute control over the thing that always mattered most—his body.” But I disagree with the theory that Jackson’s self-hatred is akin to West’s. Jackson, in his music, has always celebrated blackness, even though he fought internal demons that forced him to deform his face. His music evolved from pop to R&B—the very opposite of West leaning toward a whiter aesthetic. There’s also the overlooked militance of Jackson’s songs like “They Don’t Really Care About Us,” or even as he became whiter (partially through vitiligo), presenting the music video “Remember the Time,” which may be the only time Egypt was depicted by Hollywood with actual black people instead of the Elizabeth Taylors of the world.

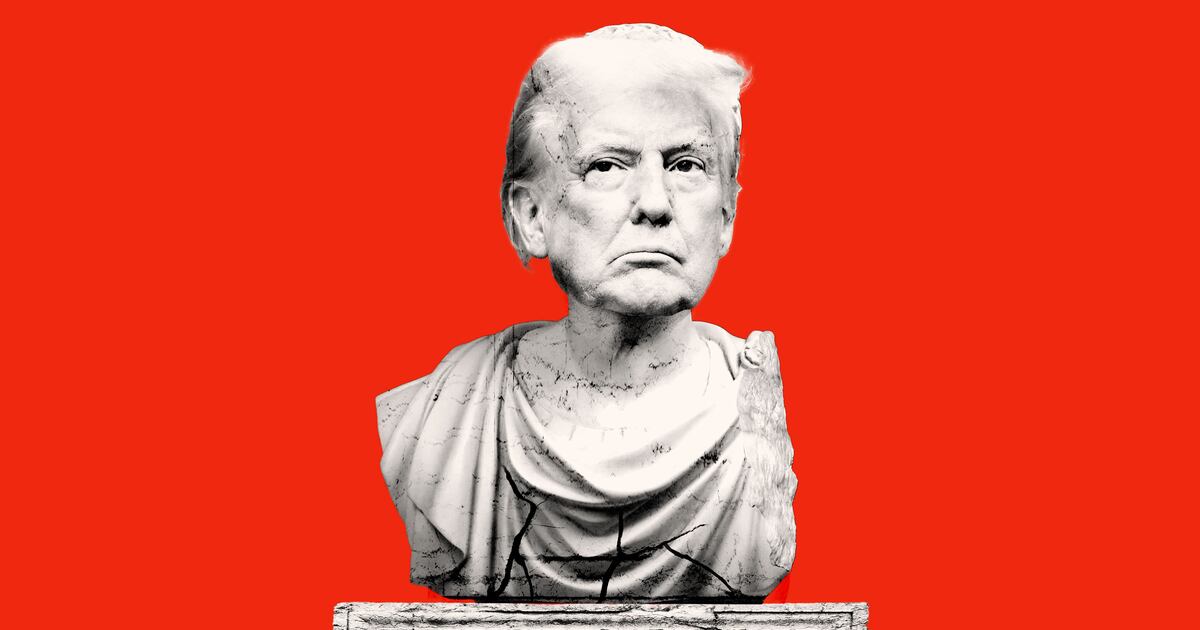

As Glover dances on a car frenetically in the video, it seems to purposefully call to mind Michael Jackson’s controversial 1991 “Black or White” music video, where he rages against racism, destroys a vehicle, then transforms into a panther. Glover doesn’t transform himself, but he leaves a path of carnage in his wake at every chance. Glover’s Jackson allusions seem more intentional to me than the Jim Crow references social media has already layered onto his video. Whether the intent is there or not, Glover’s video is eerily prescient as it arrives on the heels of Kanye West’s embrace of racial hatred, Donald Trump, and the alt-right. That is diametrically opposed to how Jackson raised his children. Take, for instance, how Paris Jackson described herself as black in Rolling Stone: “I consider myself black. [My dad] would look me in the eyes and he’d point his finger at me and he’d be like, ‘You’re black. Be proud of your roots.’”

As West makes claims that “slavery was a choice” and brands himself a “free thinker”—albeit one who notoriously doesn’t read books—Glover’s depiction of violence is perhaps a necessary bit of nihilism. His adoption of funk, soul, Southern hip-hop, and now black nihilism on a par with Richard Wright is an aesthetic he has chosen to embrace as his career evolves. Which is far from what you’d expect of a man who picked his rapper name, Childish Gambino, from a Wu-Tang Name Generator. But Glover has made a choice to embrace blackness in all of its aspects, even if that also includes our blood staining the concrete of America. It may revolt us, but it’s not a horror of his creation. The horror invented him.