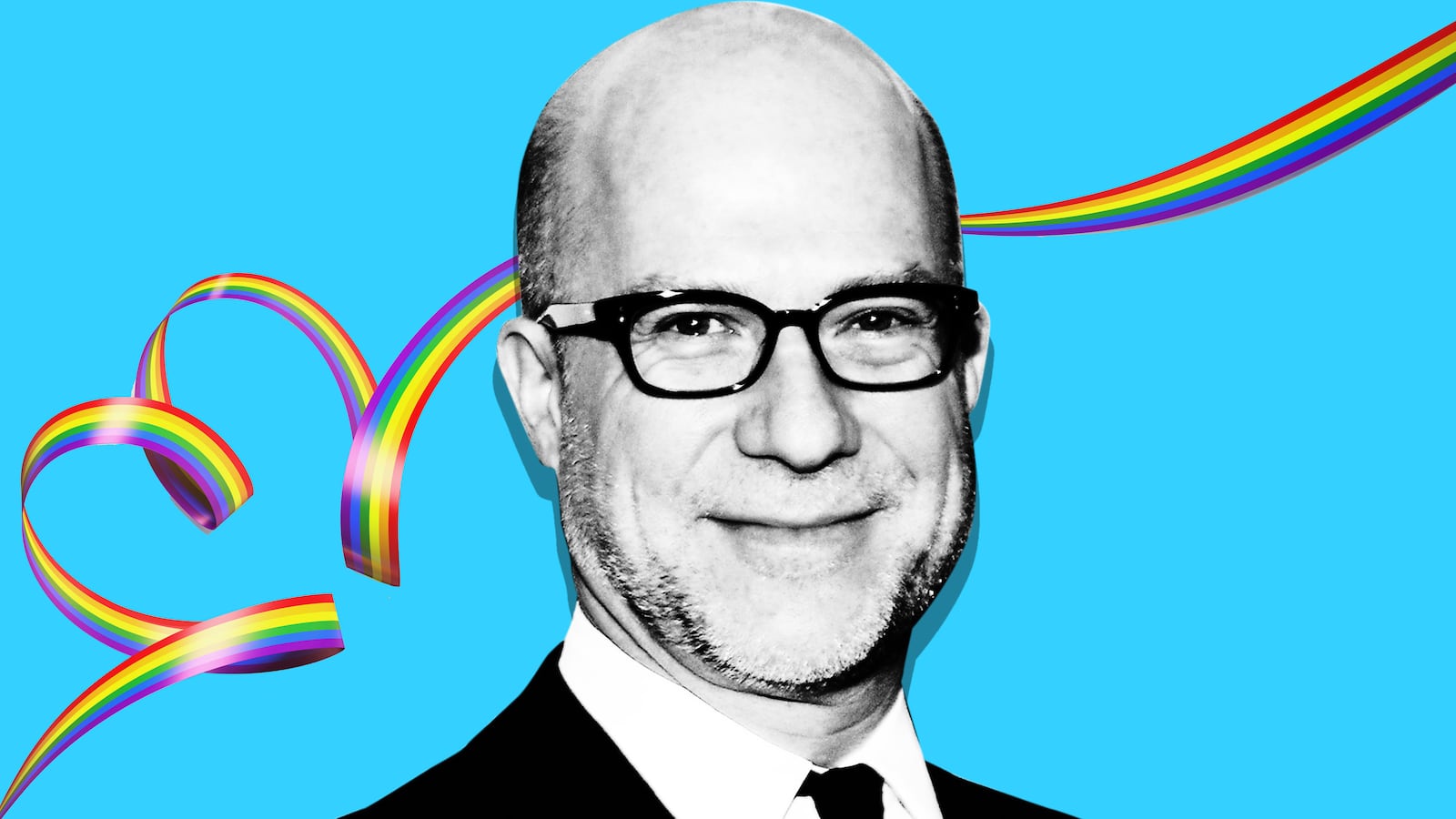

There Donald Trump sat with Melania, right in the front at Richie Jackson’s wedding to his husband, Jordan Roth, in 2012. And the presence of now-President Trump is just as imposing within Gay Like Me (Harper, $24.99), a book Richie has written for his gay son Jackson.

Richie is 54 and Jackson 19, father and son both gay from very different gay generations. Richie, a TV producer most famous for helming Nurse Jackie, wanted to write something meaningful to Jackson as he prepared to leave home to attend New York University. This was intended to prepare him for the world his son was about to enter as a gay man growing up in the Trump era: its pleasures, pitfalls, and its tumultuous politics.

“I had one shot,” Richie told The Daily Beast. “Jackson was moving out. I had to tell him everything. This is the book I didn’t have that I wished I had.”

Gay Like Me is moving, angry, sometimes funny, and shaded with inner conflicts of the author as he negotiates writing something honest as a father (don’t do this, try not to make the mistakes I made) alongside something just as honest, gay man to gay man (be you, do what you need to do, of course you’ll make your own mistakes, that’s life).

Richie has written Gay Like Me as a combined life manual, memoir, and call to action. “The dad in me wants you to meet a nice guy who treats you well, appreciates how special you are, loves all of you, and likes his own parents,” Richie writes to Jackson in Gay Like Me. “Parental me wants you to settle down early and avoid the chaos and hazards of gay-dating life. But the gay man in me is excited for you to experience your own sexual awakening; to live fully; to have adventures and intrigues; to experiment, explore, and experience; and to blend as best you can your private, public, and secret lives.”

Some of this, as it can be for many teenagers with parents getting deep, might be TMI for Jackson. But the book is written in pride and also anger and concern, at the era Jackson is growing up within, in which the Trump administration is trying to dismantle LGBTQ rights and progress.

Those politics are uncomfortably close to home. Richie’s wedding to Roth, president and majority owner of Jujamcyn Theaters (and now Instagram star), was attended by Donald and Melania, and Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner. Roth’s father, the billionaire Steven Roth, is close with—and a financial adviser to—Donald Trump. Trump, Kushner, and Steven Roth (“Pop,” as he is known to Jackson) “have business together,” Richie writes in Gay Like Me.

After the wedding, Melania tweeted her congratulations: “Congratulations @jordan_roth and @richie_jackson on a beautiful wedding! @realDonaldTrump and I adore u both!”

Trump himself sent an oddly worded note of congratulations to Richie and Jordan afterward: “Your wedding was one of the most beautiful I have ever attended, perhaps excluding my own (although I am not sure of that).”

Broadway power couple Richie and Jordan are also wealthy Democratic donors, and hosted a fundraiser for Pete Buttigieg last year. Steven Roth’s support for Trump is a source of family pain, about which both Richie and Jordan spoke candidly to The Daily Beast. (Representatives for Steven Roth did not return a request for comment.)

“It was a large wedding,” Richie said of the 2012 event, whose 600 guests included such gay luminaries as Harvey Fierstein and Larry Kramer. “My father-in-law had invited tons of people from his rough-and-tumble business world to show us off, specifically his son off. He was extremely proud and happy, and he gave us a beautiful toast.”

Richie recalled Trump sitting at the front of the ceremony, watching the cantor marry him and declare them holy. Richie is glad Trump saw and heard that, as well as him and Jordan committing to each other, and dedicate themselves to expanding the canvas of their lives; and also Steven Roth’s loving speech to his son and Richie. “Donald Trump was steps away,” Richie said. “Let him hear all of that.”

How did Richie feel about Trump’s presence at their wedding in light of all that has happened since his election?

“I don’t think about wanting to change anything about it because it was a perfect day,” Richie said. Since then, he added, “We warned our family about his intentions when he was running. It has been very painful. It is a complete betrayal that some people in our family continue to support him. It is a complete disconnect. The most generous I can be about this is that they don’t understand what it takes to be gay and don’t appreciate how important being gay is to us. It is every fiber of our beings. Sometimes I think people think being gay is like putting on a fancy shirt before they go out. They just don’t appreciate the daily exhausting vigilance it takes to be gay.”

Of Trump, he added, “I try very hard not to think about him, and spend a lot more time on people he is hurting and what to say to them.”

It doesn’t make a difference to Richie if Trump is homophobic, or parlaying homophobia for political gain. “What’s the difference? The result is the same. I would have more respect for him if he was like [Vice President] Mike Pence and just straight out homophobic.”

Richie said he knew that Trump was “coming after” LGBTQ people, after his first racist broadsides against Mexicans. “If you were ‘the other,’ you knew he was coming after you too.”

This reporter asked what relations were like within the Roth family, given Steven’s support for Trump.

“They know how I feel. I have made it very clear how I feel,” said Richie. Are family gatherings difficult? “We’ve had debates. I learned one thing from my experience with my own father. People change. I didn’t expect that to happen, and it did. He’s my husband’s father. He’s my children’s grandfather, and I will just not write him off.”

Richie did not know if Steven Roth had spoken to Trump about LGBTQ rights, “although we wish somebody, anybody would. My goal is to talk to people he is hurting. There are a lot of organizations fighting Donald Trump and what he is doing, and what I want to do with Gay Like Me is to tell young LGBTQ people: ‘You are beautiful, you are worthy, and life is waiting for you full of love, acceptance, potential, and exuberance.”

“My father has never asked me to be anything other than what I am and he has always celebrated that, and held that up,” Jordan Roth told The Daily Beast. “That was true long before this president and will be true long after. And he is my father and I love him.”

They have had conversations about Steven’s support of Trump. Jordan “cannot speak” to any conversations Steven has had (or not had) with Trump around LGBTQ rights.

Jordan doesn’t know what lies behind the distance between the lovely note Trump sent after the wedding and his anti-LGBTQ initiatives since assuming the presidency. “It’s profoundly frustrating and upsetting,” said Jordan.

The family has been “careful” not to let a schism occur over Steven Roth’s continued support of Trump.

“He is my father, and I am his son, and that is the most important thing,” said Jordan. “That is one of the many things this book offers us—that depth of love a father has for his son, and I experience that depth of love with my own father.”

When Trump was elected president, Richie wanted Jackson to know “what it means to be a gay man and what it takes to be a gay man in America right now. A war is being waged on us, and all these rainbows and ‘hashtag Love Is Love’ is masking that war. The younger generation is so complacent. They think everything is so much better. I want to tell them not to be complacent and not to diminish this gift of being LGBTQ.

“All our rights are in their infancy. The ink is not dry yet, the government is poised to take it all away. There are anti-LGBTQ bills in state legislatures, anti-LGBTQ hate groups. The Trump administration has argued at the Supreme Court that it should be OK to fire someone for being gay or trans. They think business should be able to turn away LGBTQ people. It lobbied HHS to say it was OK to deny LGBTQ people medical care. Jackson and his generation, all LGBTQ people, need to be aware of all of this.”

(left to right) Jordan Roth, Jackson, and Richie Jackson.

GettyWhen Jackson came out, he told his dad it wasn’t “a big deal.” Richie thought, “No, it really is a big deal to be gay. If you demean or ignore it, you’re taking advantage of the gift or benefits of it. I didn’t want him to grow up to be one of those people who say, ‘Being gay is just part of me, I just happen to be gay.’ Those words diminish. It breaks my heart every time someone says stuff like that.”

Jackson has told Richie that when he says this it sounds like Jackson doesn’t care, and that isn’t true. He supports his dad’s decision to write the book (and the writing of it meaning people will know he is gay). Richie hopes Jackson takes from it that “you don’t to be gay like me but you do have to be sufficiently gay in your own way and not devalue it.”

Jackson declined to comment to The Daily Beast; Richie handed him Gay Like Me just as he started college, “and he got assigned Socrates, so I got put aside. He wants to read it before talking about it.”

Richie’s cri de coeur from one generation to another is sincere. Jordan told The Daily Beast: “Every older generation thinks that every younger generation needs to understand what happened in the world before them so they can inherit it. And every younger generation thinks that there’s not much for them from what came before.”

This, said Jordan, was not unique to gay generations, “but it is particularly acute because we carry with us a history that is systematically hidden. And so if we don’t seek it out, raise it up, and shine a light on it with all the possible love in our being, it won’t be there. And we will disappear. These are things we need to know in order to know ourselves: why we feel the way we feel, why we treat each other the way we treat each other, why are treated the way we are treated, fundamental personal truths.”

This, said Jordan, is different from ‘“Know where you came from, kids.’ It’s really ‘Know yourself, and in order to know yourself know where you came from and know where you are.’ This is what Richie illuminates for us: There are many ways in which where we are not where we think we are.”

“I got to be different. I thought it was the luckiest thing in the world”

Richie and this reporter met one icy morning at the WeWork office space he rents in the Meatpacking District, near the beautiful apartment he lives in with Jordan and their other son, 3-year-old Levi—and not that far from Jackson’s new digs at NYU. The office space is where Richie decamps in the afternoon to type up his notes from writing early in the morning (a time he used to give over to reading, before his family rose). “It’s easier to be vulnerable at that time of day, to have a direct line from the heart to the page,” he said.

He said that growing up, the youngest of four children, he had two goals: to be a father and to love someone. He was born and raised on Long Island, and his family wasn’t wealthy. He worked in an ice cream shop during high school. “Ice cream shops are happy places. People come in happy and they leave happy.”

Richie grew up in a middle class, mostly Jewish neighborhood in Bellmore, “with a high school that was 98 percent Jewish, Hebrew school, Little League baseball.”

He wanted to be a parent from a young age. His mother, Carol, now 86, was a teacher for mentally disabled adults, and Richie himself was a caring little boy. “We joke with my mom that she is the only Jewish mother that didn’t teach her children ambition. She always said, ‘I want my children to be nicer, that’s all I want for my children.’”

Richie was bullied in high school. In fourth grade, a gym teacher called him “faggot” and encouraged the other boys to jump on him. “I understood I was being bullied, but I never wanted to be the same as them. To me, being gay was a gift, an escape hatch. I got to be different. The thing is, the country is 96 percent straight. We’re 4.5 percent of the population. Why be like everyone else when you have this special, unique opportunity to be different and see everything differently? I got to be different. I thought it was the luckiest thing in the world.”

He had a job in college and accrued debts. “We didn’t have a lot of money, growing up. But I never cared about money or success,” said Richie, even though he now has both. “Every decision I ever made about my career has always been through the lens of what was better for my child and now children, and my relationship.” He worked in the TV business for 30 years and never lived in L.A. He wanted to raise his family in New York City.

Growing up, Richie never heard his parents “say anything mean or bigoted about ethnicity, religion, or class.” He grew up thinking he was special in another way: The members of his family all liked each other. “We always felt valued, and they valued everyone else the same.”

An older sister, Linda, died of cancer at 45. “She died right before I met Jordan. All of a sudden it changed us. The family has never been the same. The molecular structure of the family became different. We have stayed close, but at every family holiday there is this glaring hole, and a sad veneer came over our family. Every day you prepare yourself for your parents to die, but you never expect to lose a sibling. It’s so unnerving. Nobody talks about that grief. It is so specific and strange.”

At 10:30 some mornings even now, Richie still goes to ring Linda. It was the time they used to speak.

Grief was not new territory for Richie. Many of his friends died of HIV and AIDS, and he and his then-partner, the actor B.D. Wong, also grieved the loss of Boaz, Jackson’s twin, when both boys were born.

“That’s my ball and chain,” said Richie. “I carry this grief everywhere for me, partly for friends, and partly for Boaz.” When Jackson and Boaz were born, Richie and B.D. had no time to grieve Boaz’s death because Jackson was so sick. Their living son had an oxygen tank and five medications to take twice every day.

“All our energy went into saving Jackson,” recalled Richie. “All our well-meaning family and friends said, ‘You’re lucky,’ because Jackson survived I didn’t realize you could be sad and lucky, so I held on to being lucky and ignored being sad. We never had a funeral for Boaz, we never properly mourned him, and when you don’t properly grieve, it’s like a cancer. When Jackson was little, I’d see him and also Boaz missing.”

Since then (and having broken up with Wong, with whom he has co-parented Jackson), Richie has had a lot of therapy to help him process what happened. When Jackson was little, he asked his dad why he had a scar on his tummy. Richie told him he had been born premature, been very sick, and had an operation, and that his brother Boaz had died.

Jackson asked Richie where he could look in the sky for Boaz. Wherever he wanted, his dad replied, and started to cry. Jackson asked Richie why he was crying.

“I’m sad. I miss him,” Richie replied.

“He will always be my brother,” Jackson said.

Richie paused. “He was 5 when he said that. He’s way more a deeper thinker than I ever was, and more insightful than I ever was.”

Now that Jackson is all grown up and a young man, Richie thinks he probably feels “totally over-parented.”

In the book, Richie makes clear he wants his son to settle down and have a family, while also feeling free to have lots of sex and make the kinds of mistakes he made.

“You’ve hit on the big tension of the book,” said Richie, smiling. “I wanted him to be gay. I prayed he’d be gay. It was my greatest wish for him. I was thrilled when he was 15 and he told me he was gay.”

Jackson has joked that his dads would have been disappointed if he’d come out as straight, but for Richie, “The real disappointment would be if I wanted him to be nothing like me. How could I have parented with any self-esteem if every day I was praying, ‘Please don’t be like me, please don’t be like me.’ Being gay is the best thing about me, it’s the most important thing about me. I feel blessed to be gay, and I wanted that blessing for him. We are not a defect. We are chosen. I wanted him to be chosen.”

The inner conflict for Richie is knowing the perils of being gay: how harrowing it can be for personal safety, and confronting homophobia more generally. It’s a conflict inside Richie informed by being both a parent and being gay.

“I made a lot of mistakes in college and had a really good time too. I want Jackson to have those experiences. I want him to see a hot guy on the street and experience the thrill of being attracted to each other and hook up. I want him to have safer sex. It’s an inner conflict I have. We’re not taught about LGBTQ history in school, sex, how to take care of ourselves and our partners. I have talked to Jackson about sex, so he understands everything, and also talked to him about how the guys he may have sex with in college may or may not be self-loathing. They may not be fully formed. You have to take care with those guys.”

When Richie was a teenager, he had sex with two high school teachers who paid him for sex. “I don’t think I was old enough to take responsibility,” Richie said. With the second teacher, there were dinners and trips to the opera. “He was showing me attention, and I was drinking it up. I totally accept that he could have thought they were dates. I didn’t feel it was abuse, but I didn’t have the maturity to know that transactional sex was not part of the gay experience.”

Throughout his twenties, Richie paid for sex. “It was partly low self-esteem about my attractiveness. The person you’re paying pretends you’re attractive.” (Key observational side note: Richie Jackson is attractive.)

His early sexual life was not easy. Richie recalled that the first guy he hooked up with in college broke up with him before they had both gotten out of bed. “We should not be doing this,” he said. A second guy he was dating told him he was straight, and a third guy, after they had had sex, hit Richie and told him: “How can you do that?” Richie said he “absorbed” the different rejections of each man, took it personally. “I didn’t understand it was their own shame.”

So the lesson he wants to teach Jackson is to “be vulnerable and also to protect yourself. That’s quite the dance to do.”

Richie said he had always had “a rough time” with sex. It wasn’t until he met Jordan that he found “real intimacy,” finally supplanting those other voices. The AIDS era, and its fears around HIV transmission, also had a profound effect on him. “Up until Jordan, I would never let myself be vulnerable because I was scared of being punished for having sex with men. My matriculation as a sexual adult was really traumatizing.” His 15-year relationship with Wong was “joyous in a lot of ways, and in a lot of ways didn’t work. I think I mistook friendship for a relationship.”

When Richie met Jordan in 2003, he was so nervous he “couldn’t perform sexually” for months. It was Jordan’s patience and kind-heartedness—and his advice to see a doctor, and then to take Viagra—that helped Richie regain his sexual confidence. Now, when friends bemoan an initially bad sexual experience, he tells them to give it time.

Jordan is 10 years Richie’s junior; they met when Richie was 37 and Jordan 27. They didn’t get together immediately. Jordan would say the prospect of a relationship seemed complicated for him. What if they got together, and he got to know and love Jackson, and they broke up? “I replied, ‘Why are you thinking of getting out before getting in?’ We dated cautiously, chastely, and didn’t have sex for months. I was trying to convince him to take a chance on me.” The slow courtship worked, and the men fell in love.

Jordan is now extremely well-known for his peacock displays on red carpets. “As beautiful as he looks, he is even more beautiful on the inside,” said Richie. “It is more romantic to parent with him than be on the red carpet with him. My participation is to purely enjoy his enjoyment in it. When we met he had a shaved head and wore Prada suits. To see this beautiful butterfly spread its wings is remarkable. I think he does it so we can all feel emboldened. I think he is giving us permission to be ourselves.”

“I still have just-under-the-surface rage. Ghosts occupy a chamber of my heart”

The only surprise for Jackson in the book, said Richie, will be to read about the impact of the AIDS epidemic, which Richie has not spoken about. “I just couldn’t figure out when the right time would be to tell your child about the plague you lived through. When he was growing up I always wanted him to feel safe and secure. And so much AIDS, and those years, I still have a sense of doom about every day. I still have just-under-the-surface rage. Ghosts occupy a chamber of my heart. Now I think he would understand it and won’t scare him or make him feel unsafe. As child, I worried it would.”

Richie’s own parents have read the book. His mother texted him as she read it, with messages like: “I had to put it down. I am crying, sorry.” When she read about his initial, unsettling sexual experiences, she told Richie: “I didn’t know what you were going through. This must have been gut-wrenching for you for you to write.”

Richie Jackson at his office desk, January 2020.

Tim Teeman/The Daily BeastBefore he came out, his mom had sensed Richie was gay. When he was 17, she took him to see Torch Song Trilogy in New York City. The end of that play (Richie was a co-producer of the recent Broadway revival) features many vicious fights between mother and son, one of which features Arnold’s mom telling him if she had known he was gay she would never have had him.

“My mother took me for dinner afterwards,” Richie recalled. “She said, ‘If you ever came home and said that you were gay, I would never react like that mother in the play.’ I had friends at NYU in 1982 who weren’t so lucky to have parents like mine, who gave me that safety net.” Richie came out to his mother, who told his father, Paul (now 93), despite Richie asking her not to. “He called me into his study, and said, ‘It’s just a phase. All gay men are sad and lonely. I see those men on my way to work.’”

Notwithstanding his father’s apparently super-sharp inner-gaydar, Richie was shocked. “But I didn’t realize his first reaction would not be his last reaction. I thought it would be forever.”

The next day, Richie’s father reassured him that he loved him. Things were difficult for a time, culminating in Richie being forbidden to bring his then-partner to his sister’s wedding. “It felt like I was being told to go back into the closet. It was weird. I didn’t have any shame, but other people were telling me it was something to be ashamed of.”

Richie’s father eventually fully accepted him. He saw him with Wong and his discomfort disappeared. “My dad isn’t a bigot. He has not hate in his heart for anybody. I think his own moral fiber took over.” His dad “wasn’t the kind of dad to throw a ball in the backyard, and that was painful for me.”

Richie’s mom read to her husband the part in which Richie recalls his father’s initial negative reaction to Richie’s coming out. His father said of his son’s recollection, “I guess he’s right.” For Richie, it was more difficult to write about his own unmet expectations of his father when he was a little boy.

Thinking of himself and Jordan now bringing up Levi, Richie said it was “very strange” to raise children in the Trump era. Bringing up Jackson, the prohibitions were “no TV, video games, screens, cellphones. But now the world has gotten so mean, it is hard to parent with the optimism required to parent a 3-year-old while holding off the despair I feel about the world. It’s a daily challenge.

“But the best act of resistance is parenting. We’re planting empathy in a world devoid of it. Trump has abolished empathy in this country. You have to be focused. Parenting is an awesome responsibility. Everything you do they are watching and clocking. I don’t want Levi to be afraid. My job is to keep him safe and love him.”

Richie thinks about how Levi is too young to know that Richie has never let his “guard down” as a gay adult; that he wonders when it is safe to hold Jordan’s hand and kiss him on the street; that when they travel they take all the certification for their children with them, should they find themselves anywhere that would question their validity as gay parents. A friend who lives in Midtown is called a “fag” when he takes his dog out for a walk. Homophobia can bloom poisonously, sometimes violently, anywhere.

“It’s an indescribable feeling,” said Jordan, “to walk through the day knowing that the legitimacy of your parenthood, the legitimacy of this most fundamental human bond, could be challenged or called into question, to worry, ‘This husband, these children, don’t all have the same last name.’ What are the questions and assumptions going to be? It’s a fundamental fear of being delegitimized as a family. And it happens, and it also doesn’t happen. There are lovely, celebratory moments with people, when you are treated with equality—or, even better, with joy, love, warmth, and humanity. It’s the line we all walk every day—protecting ourselves and allowing people to be wonderful. It’s only when you exhale that you realize you’ve been holding your breath.”

“You need to have double vision as a gay person,” said Richie. “Every LGBTQ person develops this ability to know how the world around them sees them to keep safe, and then a ‘gay view’ which gives you a unique, special view of the world.” He has spoken to Jackson abut celebrating his homosexuality and developing his self-esteem, and knowing LGBTQ history and culture, and those whose bravery and creativity have lit so many paths to the present day. And he has also helped him develop a “gay guard” to protect himself out in the world—another LGBTQ balancing act.

How would Richie have felt if Jackson had been straight? “I would have been OK. I’m much happier he is gay. But one of the most important parenting lessons you learn is that you parent the child you have, not the one you thought you wanted. Jordan and my basic parenting rule is, ‘Follow your child. Don’t make them follow you.’ You just expand on what they want to be doing.”

Jordan echoed his husband’s thoughts and added, “When you have two children, you have two different children to parent. Part of the unique opportunity of parenting and part of the joy is finding the parent you are for this child and then finding the parent you are for that child. The ability to do that is affected by who you are at those different times.”

When Jackson got intimate with a partner for the first time, Richie and Jordan allowed them to do so in Jackson’s room at home, “because doing it outside, in the park or wherever, is not safe, and for them to be safe was my biggest goal.”

How about Levi; does Richie care if he is LGBTQ or straight? “We raise him as we did Jackson: love yourself, don’t edit yourself, do not demean yourself, whatever you are is beautiful. Whatever he is when he grows up we will follow and celebrate. I do think being gay is better: You get to be special and different, and part of a creative, vibrant community. And if he’s straight,” Richie smiled, “well, we can be the gay guys that raised a really good straight man—and the world really needs them.”

“If he said, ‘God, my father loves me to have done this for me, and to bare his soul for me,’ that would be everything.”

Richie feels his mortality most sharply when thinking about Levi. He is 54, and Levi 3. He thinks about how old he will be when Levi is in college, or whether he will miss Jackson’s wedding, or miss out on time with Jordan, who is 10 years younger than he is. “And I didn’t imagine being 54. When I was at college, I was going to funerals for friends. My roommate died of AIDS. I always assumed I’d be next. To be 54 is a bit of a surprise.”

Every parent should write a letter to their child before that child leaves home, Richie said. “Don’t edit yourself, put it all down, you’re getting everything said you need to.” With Gay Like Me finished, he is working on a memoir, unpacking more of his eventful life.

For Jordan, “every reason” that he fell in love with Richie “is on every page” of Gay Like Me. “I am so proud of him. He has continued through this whole process digging into his heart and brain to find all of this. I am a person who believes deeply in self-examination and self-expression. I knew this was a story he needed to tell and a story Jackson needed to hear. I hope Jackson digests all of it. And I hope he feels the extraordinary depth of love”—his voice breaks—“and now I’m crying, this book carries. I hope it offers to him, and to so many other people, the ocean on which this story flows: that depth of love a parent has for a child.”

What does Richie hope that Jackson takes from the book?

“I obviously want him to take my lessons and appreciate the information I’m imparting, and wisdom. But if he closed the book and said ‘God, my father loves me to have done this for me, and to bare his soul for me,’ that would be everything.”

Jackson is a freshman at NYU and interested in urban planning. Richie said that he wants a career in mass transportation and ultimately to solve the problems of the New York City subway. (Go, Jackson!)

He’s only a few minutes’ walk away, and Richie, Jordan, and Levi see him at least once a week. “I think he misses Levi more than us,” said Richie, smiling. Geographically near as Jackson is, Richie misses his son—and, of course, Jackson is still to his dad that very ill little baby who both survived and thrived to become the young man he now is.

“I hug him tightly when I see him,” Richie said. “I hold him a little too long. Every once in a while he forgets he’s 19 and holds my hand. I stop breathing when he does that and hope he doesn’t realize he’s holding my hand, so I can hold it a little longer.”

Richie Jackson’s voice clotted a little, and he paused. “My book is really me holding on to him a little bit longer.”