If you’re like most people, I was once like you: I hated the Grateful Dead.

Even as a classic rock-loving teen in the 1990s, I could not fathom the appeal. The studio albums (with a couple of exceptions) were goofy and uninspired. The badly recorded tapes of thousands of live shows did nothing for me. The music struck me as aimless and dreary; the lyrics sounded like they were written by guys who were born old.

Indeed, the band’s “I’m so tired of the road” anthem, “Truckin,’” was released a mere five years into their career. (“What a long strange trip it’s been” is a truly odd, world-weary lament for a bunch of twenty-something California bohemians in 1970.)

Yet somehow these days, few things enliven me like a good Dead show—thanks to the miracle of remastering and the band releasing hundreds of “official” recordings on streaming services.

And, despite being a (metaphorical) hippie-puncher for much of my life, the aura of the Dead now makes me feel young, free, and… healthy. (The last of those is a particularly perverse association for a band so synonymous with drugs and debauchery that its de facto leader, Jerry Garcia, essentially died of old age at 53.)

I guess you could call me a mid-life Deadhead. How could this have happened?

LET THERE BE SONGS TO FILL THE AIR

I’ve written about this a few times before and don’t care to get into the gory details again, but in my mid-thirties I experienced a series of traumas that culminated in the most dangerous, long-term depression I’ve yet endured. Luckily, that was the darkness before the dawn.

I committed to talk therapy. I began a regimen of daily meditation. And for a time, I cut out alcohol entirely.

I also took up running—something I’ve hated my entire life, even during my more youthful and athletic days. And without any specific intention to make it so, as I clomped along cement sidewalks and overcrowded running tracks, live Dead shows became my go-to soundtrack.

Then I started going to see various Dead-adjacent bands—always featuring former Grateful Dead bandmates and/or younger veterans of those same “official” Dead projects.

Dead & Company provided the slow-tempo, nostalgic stadium show experience led by Dead rhythm guitarist Bob Weir. Dead bassist Phil Lesh’s shows featured a constantly changing pick-up band of virtuoso (and sometimes famous) musicians.

But for my money the can’t miss shows are performed by Joe Russo’s Almost Dead—aka JRAD—a “cover band” made up of younger veterans of various Dead side projects that completely reimagines the Dead’s music with a more muscular, rhythmic energy.

It started slow, but it’s gotten to the point that I play the Dead often enough that my kids have their own shorthand to mock me for it (as they should). And my wife has patiently indulged my need to travel to see some of these shows, typically with friends going through relatable midlife crises—and becoming latecomer Deadheads.

I still feel somewhat self-conscious when talking about it to non-Heads, but the Dead—and all its ancillary experiences over the past decade—have brought me comfort, new friendships, even emotional steadiness. I’m less judgmental, more empathic, and open to discovery (though my capacity for forgiveness could still use a little more seasoning).

And though I still find the experience of dancing to shitty pop music at weddings physically painful, I can dance to the Dead like no one’s watching—proving that old dogs can learn new tricks when the right treat is available.

You’ll still never see me in tie-dye, or stinking of patchouli, or tolerating anything associated with Dave Matthews Band. But after a few decades of generally loathing the Grateful Dead, Deadheads, and ostentatious, boomer-created, hippie culture—what can I say but to call me what I am?

IF YOU GET CONFUSED, LISTEN TO THE MUSIC PLAY

The whole “late in life” Deadhead thing is apparently… a thing.

A few years ago, I asked a few of my snobbiest music pals if they’d ever dug into some of these old shows—and several of them lit up, admitting they had been going down the same Dead rabbit holes, and they, too, had been embarrassed to admit it!

New York Times reporter Nick Confessore recently tweeted about “coming to Dead fandom a little late in life.” The writer Angela Brussel wrote in 2019 about how discovering the Dead as an adult “suddenly, miraculously” helped her embrace her own mortality. The journalist Aaron Gilbreath wrote a Substack essay last year about how he went from a lifetime of loathing the Dead to falling in love with their music as “an antidote to pandemic malaise” in his mid-forties.

“I grew up in the 1990s with a reflexive disdain for hippies. Two years into the COVID pandemic, at 46, I became a huge Grateful Dead fan,” Gilbreath wrote (channeling my own journey from hater to bus-rider).

“We tried to stay positive. We tried to live, but it was depressing. No big trips, no parties, no concerts… You moved from one end to the other, keeping the same predictable course,” Gilbreath added. But, in discovering the Dead, he wrote that the music “expanded our world and infused it with joy—not just in our minds, but in our bodies, too. Singing and dancing to their grooves, I was a happier, more relaxed person. I felt buoyant, lighter on my feet. It was like the music triggered a mushroom trip memory and brought all the neurological benefits without any of the drugs. Sixties kids used the term ‘afterglow’ for the peaceful state that follows a psychedelic experience. We needed it, and we got it, from listening to our new favorite band.”

But it’s this passage from Gilbreath that really nails the experience: “Embracing The Dead in mid-life revealed a lot about myself philosophically, too—my old, stifling ideas, my blind spots, and how much I shared with the very same hippies I wanted to loathe.”

Writing for Uproxx, Steven Hyden explained the appeal of becoming a late-in-life Deadhead: “it does offer a tremendous opportunity for seemingly endless discovery. This, more than anything, explains why I and perhaps others have been drawn into this world relatively late in life. Getting into the Dead replicates the feeling I had as a kid learning about music for the first time, when all artists were new and classic albums I had never heard were blowing my mind every day.”

Somehow, this perennially divisive band continues to find new obsessive fans—like us—almost 60 years after forming and almost 30 years after disbanding.

AT LEAST I’M ENJOYING THE RIDE

With few exceptions, it’s never been my thing to travel to see a band. (Though I’ve been to hundreds of shows, I don’t care for music festivals. They’re uncomfortable, the sound is shit, and who the fuck wants to spend well over $1,000 on plane, hotel, and tickets to stand around in the sun for 16 hours—three days in a row?!!?)

But as Deadheads will tell you, no two Dead shows are the same. Setlists are never duplicated, unrepeatable improvisations happen constantly, and nearly every show has been recorded by fans and subsequently disseminated widely. Each show is a “show,” not merely a concert. And each is its own unique experience.

Over the past seven years, I’ve seen more than 30 “Dead” shows of various iterations, and have even flown on a plane to get to some of them. (And when I can’t get to out of town shows, I’ll often fork out $15 to watch an official livestream.)

However ridiculous it seems to be in my forties and being this committed to following “cover bands” around the country, I’ve heard confirmation from hardcore Deadheads who’ve “seen Jerry” that JRAD, in particular, is creating something entirely new and amazing out of the Dead’s relatively ancient songbook.

In his book, Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the Center of Classic Rock, Hyden marveled of JRAD: “My interest in this band feels a little weird to me—has my classic-rock obsession come to this, love a band that covers an older band that I love?” But, he later notes, the surviving members of the Dead took “a lead role in handpicking the people who will carry their music forward once they’re gone.”

One of the most exhilarating live music experiences of my life came last January, when JRAD played on the 10th anniversary of their first gig, at the same venue, Brooklyn Bowl, and Bob Weir shocked the crowd by playing two songs with the “cover band.”

You could almost see the torch being passed. In a sense, JRAD is like the Mingus Big Band—a “legitimate” musical revue keeping the spirit of a dead artist’s music alive by evolving it with the times—and the shared energy of a band and its audience.

In 2016, members of the venerable indie rock group The National recruited scores of their contemporaries to contribute to a massive collection of Dead covers called Day of the Dead. They were, to an extent, looking to bring the music to their comparatively younger audiences—who would typically (and understandably) dismiss the Dead as hippie pablum.

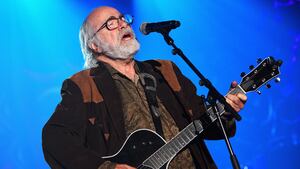

And if anything ever cured me of anti-Dead elitism, it was learning that one of my favorites—the snotty, erudite, punkish, British singer-songwriter Elvis Costello (about as far as one could get from the Dead, image-wise)—took inspiration from the Dead to form his first band. Elvis even performed a series of shows in San Francisco last year that were entirely comprised of Grateful Dead songs.

If the avatar of late-1970s working class pop-punk anger could be a Deadhead, then so could we all.

STRANGEST OF PLACES IF YOU LOOK AT IT RIGHT

Jerry Garcia once described the Dead’s music as “licorice”—meaning you either love it or simply don’t have a taste for it.

He was right, and it’s one of the main reasons I would never proselytize on behalf of the Dead. If it’s not your thing, you’re not necessarily wrong. (And if it hasn’t hit you yet, I can fully attest that somewhere down the line, it might!)

The most prominent of Grateful Dead offshoots, Dead & Company, will play what’s been billed as the final show of their final tour (yeah, sure) this weekend in the San Francisco Bay area, the band’s birthplace. I’ll sincerely miss Dead & Co.’s big, dumb stadium shows, swaying peacefully beside tens of thousands of olds, youngs, and newbies.

But I’m not sad, because the Dead’s songbook will endure, it will evolve. There will be more shows. And there will always be new stuff to discover among the old stuff.

As Gilbreath wrote of the sense of youthful discovery he’s found in the Dead’s music: “Once you reach a certain age, it’s impossible to feel that way again, which is why so many people drift away from discovery in middle age and stick with the music they know. With the Grateful Dead, however, there’s always a new tape that includes an amazing ‘China>Rider’ you’ve never heard. Your mind never stops being blown. You put a Dead tape on, and time stops. Jerry is alive again, and the world seems exciting and fresh once more.”

That I could feel this sense of wonder in my forties did not occur to me before I allowed the Dead into my life. And it’s played a part in this crusty middle-aged man’s capacity to evolve, to let go of grudges, and write new chapters without fear of betraying one’s past self. The ego that protects you is only occasionally your friend, it’s better to make new, real friends—and discover more marvels in plain sight—all the time.

“That path is for your steps alone.”