Well, here’s an anti-Semite’s worst nightmare: the likeness of a Jew on an American banknote.

And that’s only a little way into Dara Horn’s beguiling new novel, the third by the 31-year-old named among Granta’s “Best Young American Novelists,” who just six years ago stood up in front of a gala full of her elders and accepted, as the youngest winner to date, the National Jewish Book Award for her first novel, In the Image. At 15, she was also nominated for a National Magazine Award, because of an article in Hadassah, the first for a Jewish publication. She was the only one in braces at that awards ceremony. Then as now, when she mentioned she grew up in Short Hills, N.J., it put people in mind of Philip Roth.

“There’ve been editorials since last year’s election saying ‘the Civil War is finally over.’ I’m not sure if that’s true.”

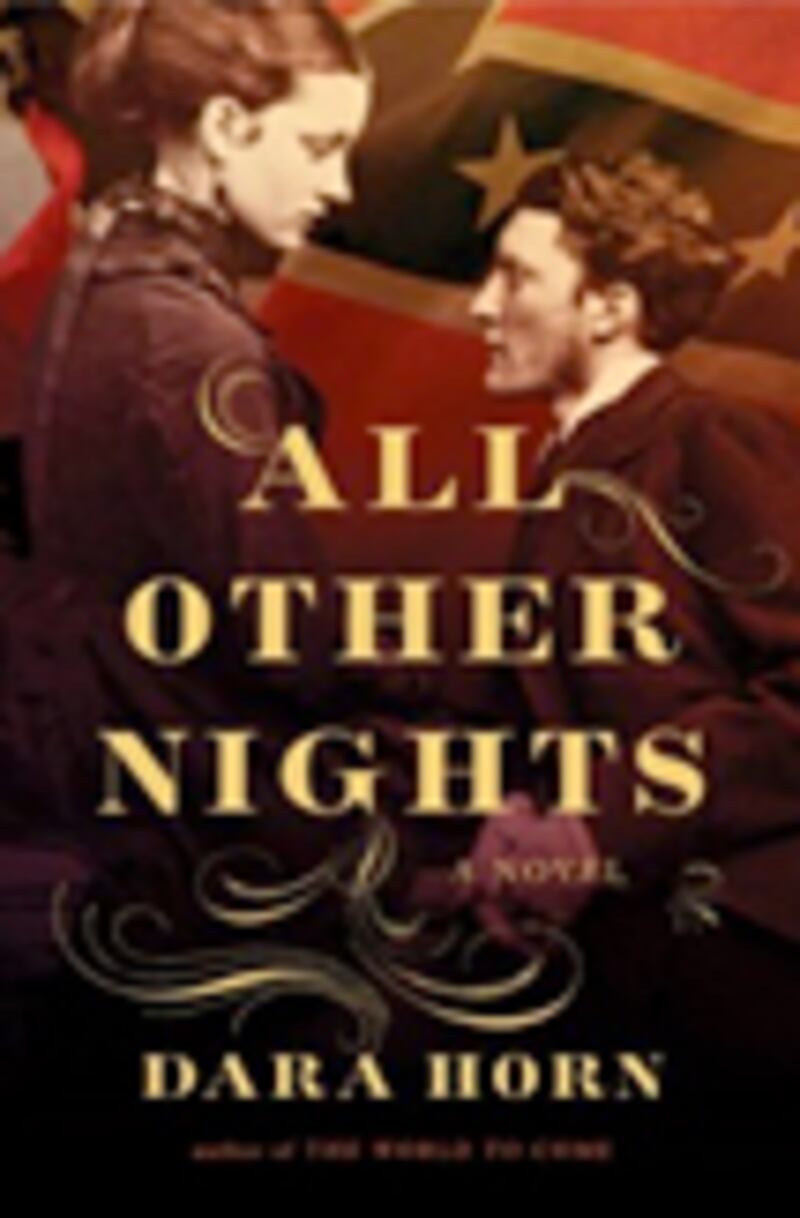

But All Other Nights is no Goodbye Columbus. It’s more a book for the multitudes who have been clamoring for a way to celebrate the Lincoln bicentennial and Passover at the same time.

“Although I didn’t plan it this way,” Horn said, “the election of Obama has gotten a lot of people talking about the Civil War again.” The novel, a meditation on freedom and free will wrapped in a spy story, a romance, a family history, and a country’s suffering, sees the cataclysm through the eyes of young businessman-in-waiting Jacob Rappaport of New York, who joins the Union Army to escape an arranged marriage, and tumbles into the morass of intrigues permeating the Jewish community caught (and caught up) in the War Between the States.

Sitting out in the sunshine after a rainstorm in the backyard of the new house in Short Hills that a pregnant Horn moved to from Manhattan in December with her husband (a lawyer), her computer, and her two children under 3½, she talked about meddlesome parents and unhappy children. “Jacob is someone who doesn’t really know who he is until the end of the book, and that’s a kind of person it’s hard to like,” she conceded. “He hasn’t yet learned how to say no, especially to his parents, and he has to confront the conflict between the American mythology that we are each self-made, people without a past, and the Jewish tradition that you are who your ancestors are. He sees at the end that it doesn’t have to be a conflict. It’s like a lot of what the North and South were fighting about. There’s a saying, ‘Jews are like everyone else, except more so.’”

There are also plenty of scenes of them ripping through bodices and petticoats to have sex.

The Jew on the banknote—it’s a Confederate $2 bill—was Judah Benjamin, Secretary of State and close confidant to Jefferson Davis. He embodies Horn’s belief that “the boundaries between good and evil don’t run between people but within them.” Benjamin, like so many of the 130,000 Jews living in the United States at the time—some families already for generations—was among those whose loyalties lay with the places where, in contrast to Europe, Jews had been able for the first time to own land and put down deep roots. “The battle about slavery was in part a moral conflict,” said Horn, “but it was also between the agrarian, land-owning South, with its traditional ways, including institutionalized racism, and the industrializing North.”

Because her book is historical fiction and not history, Horn is also able to drop in hints she gleaned from her research that the brilliant and secretive Benjamin enjoyed an enduringly intimate relationship with his absentee wife’s brother. “History,” she said, “is written about the times we are living in as much as about the past.”

And the Civil War, Horn argues, reeked of paradox. It was Ulysses S. Grant, the Union general, the novel points out, who in 1862 issued General Order No. 11, expelling all Jews from Tennessee, Kentucky and Mississippi. Shades of Roth’s The Plot Against America, Horn acknowledges. But also of mass displacements and deportations throughout history and to this day.

On the other hand, the order only lasted three weeks because, “a delegation of 35 Jewish families expelled from Paducah, Kentucky, were able to go see Lincoln in the White House,” Horn said, “and he was like, ‘Wow, I never intended that to happen,’ and he overturned it. That could only have happened here.”

Grant’s vague accusation was that the Jews were war profiteers, and certainly, the novel underlines, while most Americans at the time stayed put where they were born, the ties among the Jewish community throughout the States made for greater mobility there, commercial and otherwise. “Lehman Brothers, may they rest in peace,” said Horn (she may be the only one), “got their start as cotton brokers, and the fortune was made running the Blockade.”

Horn herself was raised in the conservative movement of Judaism, by her mother, a history teacher, and her father, a dentist, who live a two-minute drive away, in the house where she grew up. The family also traveled a lot, and “we used to joke that my parents were spies,” she said. “Why else would you go to Cambodia? I’m different from most in my generation. I’m very close to my family.”

Though she has relocated to suburbia “only with reluctance—I was running out of cabinet space,” she added there’s nothing like the Horn family seder, where she and her three siblings—both sisters are also novelists, and her brother an animator for Comedy Central—have always mounted skits gently ribbing popular culture’s zeitgeist. “My parents encouraged us to be creative,” said Horn, who was active in the Hillel Dramatic Society at Harvard. “At Passover, we do parodies of movies, TV ,and Broadway musicals. The year of Brokeback Mountain, we wrote ‘Moses I Can’t Quit You.’ Another, we did “A Tyrannical Mind.’ Because the crowd is so young this year, it’ll be ‘Elmo Escapes from Egypt.’ Pharaoh is played by Oscar the Grouch.”

Horn met her husband at Harvard Hillel, when she was a sophomore and he was a first-year law student. They married shortly after she graduated, summa cum laude. More recently, she got her PhD in comparative literature from Harvard, with an emphasis on Hebrew and Yiddish studies, and publishes and lectures widely in her scholarly field.

In All Other Nights, Jacob sings the story of Passover, in Hebrew in a deserted cemetery, to a black man on the run to freedom.

The parallels between the history contained in All Other Nights and the present compelled Horn to write the novel. “I wouldn’t have been interested 10 years ago,” she said, “but the country has grown so polarized, and a lot of that was rooted in the Civil War. The red states were the Confederacy, the blue states the Union, or you can call them conservative versus liberal, traditionalist versus those who value progress and social justice. There’ve been editorials since last year’s election saying ‘the Civil War is finally over.’ I’m not sure if that’s true.”

Many American Jews’ views of Israel, she feels, manifest the same polarities. “Israel is one of many contemporary issues, like so much also in American foreign policy, that pits tradition and conservatism versus progress, yet Judaism has a strong tradition of social progress, too.”

More rain clouds are gathering. Horn gets ready to go inside.

She suspects, she said, that her next novel will be about the Great Depression.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Celia McGee has been the media columnist of the New York Daily News and the publishing columnist for The New York Observer . She currently covers the arts and publishing for The New York Times and others.