Of course, all the throbbing penises, phallic flowers, and hot bodies Robert Mapplethorpe fans could wish for are present at the two retrospectives of his work at Los Angeles’ Getty (to July 31) and LACMA (also to July 31) museums.

Of the two, the first is more formal and sober; the second a more unexpected and surprising bran-tub of Mapplethorpe’s work through the years. Both exhibitions come in the wake of HBO’s recent documentary, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures. Twenty-seven years after his death, we are having a Mapplethorpe moment.

Actually, every day in our body-obsessed culture carries a tinge of Mapplethorpe—our beefcake and gym-ripped Adonises in gay and fitness magazines are shot Mapplethorpe-lite if you like. In the 1970s and 1980s, Mapplethorpe—alongside the likes of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat—produced work that blurred the boundaries around sex and power. He partied with the elite, and was courted and consumed by the elite—and was also down among the downtowners (he knew and photographed Nan Goldin and Kathy Acker), and immersed in the gay sexual cultures of the era. If his work traversed boundaries, so did he.

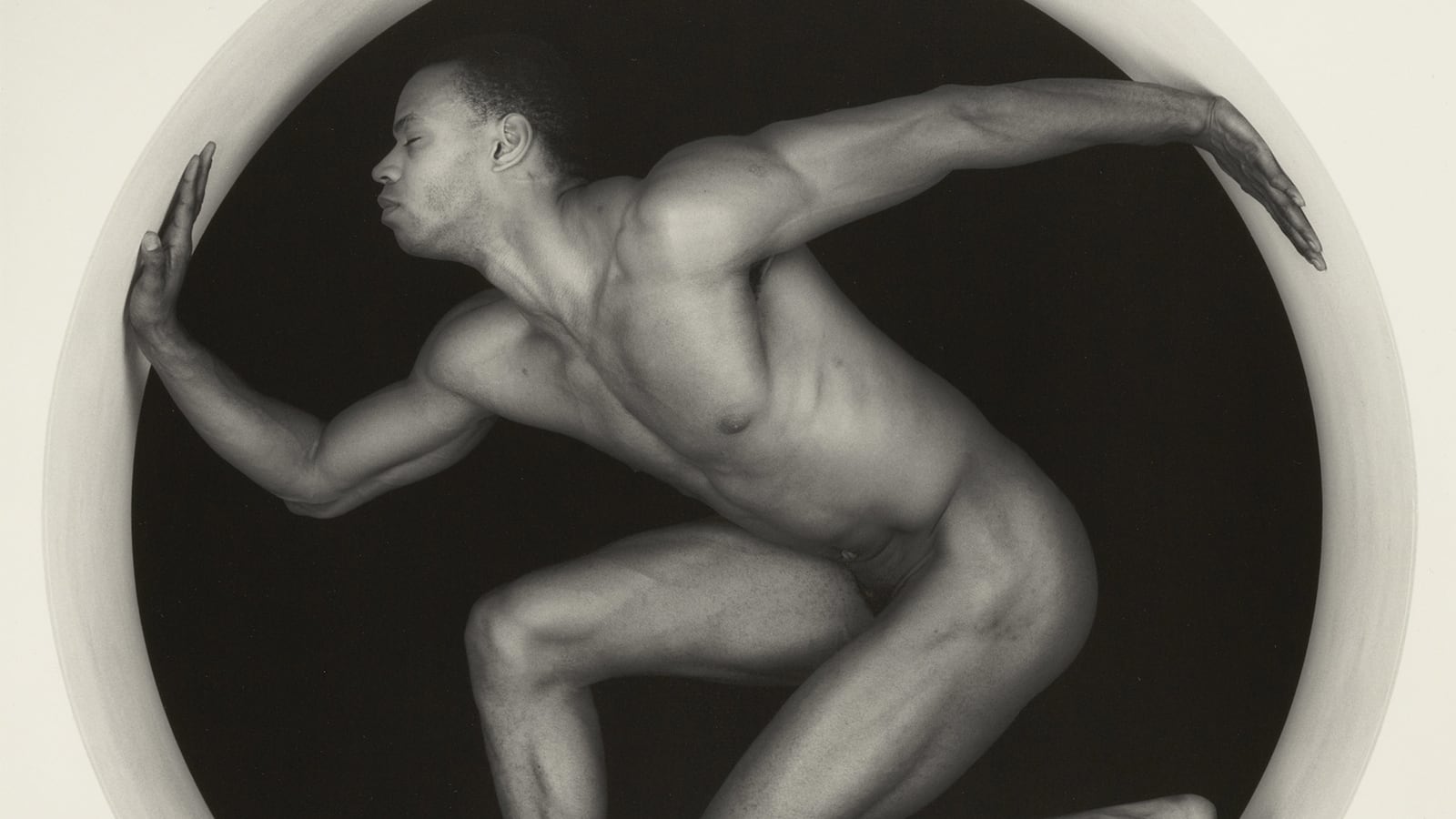

Mapplethorpe’s photography, and the fame and notoriety it brought him, was based on frank, blunt, and mischievous evocations of sex and sexuality. His photographs of the male form were not romantic or cutesy, or designed just to elicit gasps of ab-lovers—but challenging, uneasy, and direct. He made the muscleboy complicated, human, and passionate—domineering and sexy for sure, and also vulnerable.

ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE: EDGE OF DESIRE (PHOTOS)

The HBO documentary opens with the fury of Jesse Helms, who—in 1989, just after the artist had died—sought to make Mapplethorpe’s work a cultural cause célèbre. What outraged the homophobic Helms so much is there, in a special display case of the Getty: the most sexual of Mapplethorpe images.

It’s strange, looking at the famous picture of the bullwhip emerging from Mapplethorpe’s ass, or the black man’s cock flopping through an open fly of a pair of suit trousers. They are still shocking, gorgeous, jolting. The knife next to a penis, an implied multi-gender three-way: Mapplethorpe’s images still occupy as charged a place on the faultline of race, gender, and sexuality as they always did. Is Mapplethorpe celebrating or objectifying the black male body, or both? The question is not resolved simply in the two LA shows—but what is uncontested is that he endows those bodies with an unapologetically showy and transfixing power. In his work, he said, he wanted to capture “perfection in form.”

Mapplethorpe’s images are indeed beautiful to look at: beautifully lit, beautifully structured, beautifully shot. The sex acts, the objectification of beautiful bodies, may be extreme, but so is an elegiac majesty to whatever Mapplethorpe captures. You see every strain of a muscle, every six pack, every sinew—and also all of those frozen in a moment. The same goes for his more conventional portraits of people—like the English high-society gals he got to know in the 1970s.

His sexual images, you realize after seeing a lifetime of them finally grouped together so coherently and carefully curated, were informed by pleasure, danger, and desire. Mapplethorpe’s intention wasn’t simply the fetishization of the body, or the easy and sexual celebration of it.

This was a time of widespread homophobia and fear of homosexuality, and Mapplethorpe wasn’t interested in serving up pasteurized and safe images of gayness in response.

Helms’s fury was because Mapplethorpe very visually reveled in sexual subcultures, and delighted in unsettling and confronting the viewer with naked, raw desire and role-play.

He doesn’t play safe, he doesn’t take us gently by the hand, and the pictures come with their own innate politics: Mapplethorpe’s images of male bodies displayed, entwined, stretched, and horny were taken at a time when so many were dying of HIV and AIDS—when the gay male body was itself was under horrific mass attack. His pictures are gorgeous, even glamorous, but also dark, questioning, sexy, rude, in-your-face, transgressive. They still are, even in these all-knowing times.

At the Getty, Mapplethorpe’s pictures of flowers and stems take their place alongside the pictures of handsome models, and then—at the end—the famous self-portrait Mapplethorpe took of himself with a cane, the story of an artistic life etched into his features, and a dancing mischief in his eyes.

LACMA’s Mapplethorpe show is more intriguing. Here you will see shots you have never seen on postcards or at smaller gallery shows—an image of a sexy model in sports shorts ushers the spectator into an examination of Mapplethorpe’s early years as an artist: the collages that used pictures from physique magazines and advertisements for cigarettes.

A self-image far from the sexy parade that would follow just a few years later sees Mapplethorpe capture his face as a series of abstract swirls and slashes. Another installation features the Virgin Mary, a leather glove, bracelet, and a cage.

There are other pictures of skulls, and in a display case a set of release letters for models Mapplethorpe found at the Saint nightclub. And there are some beautiful images of those models, with their gorgeous bodies, or in mesh tees, or blue underwear, or in bondage gear, and extreme sexual positions.

There are images of Mapplethorpe’s famous sitters, like Deborah Harry, Iggy Pop, Andy Warhol, Kathy Acker, Sean Young, and (most stunningly) Isabella Rossellini--as well as a series of images of muses like Patti Smith and Lisa Lyon. An intriguing final series of images shows Mapplethorpe himself, as shot by famous photographers like David Bailey—there are so few of these, it shows how much he preferred to be behind the camera rather than in front of it.

The end of the show is a room of non-Mapplethorpe images and installations that echo his preoccupations with sex, sexuality, and the human body. It has been 27 years since he died, and now we live in a culture awash in representations of the male body, mostly made safe. Hunks are wallpapered across magazines and the internet. Mapplethorpe reminds us that in more dangerous times, in less sexually open times, the male body came with its own thrilling sense of peril, drenched in sex and sexual pleasure, and also mystery, frailty, and ambiguity.

Mapplethorpe doesn’t make anything safe, and via his relentless art of confrontation he reminds us just how—like the glimmering blades in some of his images—how sharp the knife-edge of sex and desire can be. Jesse Helms’s fury—ugly, narrow, and bigoted as it was—was also the best kind of compliment.